How does a pitcher of, at best, minimal skills, who made his professional debut at age 30, appeared in only two games (two innings) and never recorded an MLB win earn the nickname “Victory?”

Well, it helps if your middle name is “Victor.” It also helps if you believe in fortune tellers, are slightly “off balance” and can find a manager and team that can be convinced you are a good luck charm that can bring them a successful trip to the World Series. All those forces came together to create a “perfect storm” in the short, zany and improbable life and major league “career” of Charles ”Victory” Faust.

Side note: BBRT has often talked about how, when looking into baseball “tidbits,” one thing can often lead to another – and another – and another. In this case, research BBRT was putting together a post on a unique connection between two players who were hit by a pitch (in their first – and for one only – plate appearance) fifty years apart led BBRT to a look at a third player who also was clipped by a pitch in his first (and only) MLB plate appearance. For a look at the post that led to this article, click here. Anyway, that’s the roundabout way I got to this post about Charles “Victory” Faust.

As I prepared this post, it became clear that record-keeping (and even “eye-witnessing”) were not exact sciences among ballplayers in the early 1900s. I worked to distinguish between myth and reality as I looked into the life of Charles Faust, but can’t guarantee a bit of myth may have slipped by. Still, even when you discount likely myth, there is plenty of magic in this Faust-ian tale.

Charles Victor Faust – an awkward and somewhat slow fellow in many ways – grew up on a Kansas farm and did not appear to have an overly bright future. That is, not until the spring of 1911, when he availed himself of a country fair fortune teller – who told him (among other things) that he was destined to marry a California woman named Lulu and pitch the New York Giants to a World Series championship. The 30-year-old Faust – apparently with child-like enthusiasm, intellect and trust – took the predictions to heart. Despite his total inexperience as a pitcher, Faust’s focus in life became finding a way to convince Giants’ Manager John McGraw to enable him to pursue his destiny.

In late July, Faust traveled to Saint Louis, where the Giants were facing the Cardinals. Now, there are a couple of versions of what took place in Saint Louis. One says that Faust approached McGraw at the team’s hotel and related the fortune teller’s prediction, promising that he would fulfill his destiny and pitch the Giants to the World Championship. The other is that Faust bought a ticket to the Giants/Cardinals game and, during pre-game warm-ups, simply stepped out onto the field and approached McGraw.

In either case, Faust – who may have seemed a bit odd to McGraw, but was certainly sincere enough – got his tryout with during that day’s pre-game warmups. (The tendency of baseball players and managers of the time toward superstition may have swayed McGraw to want to explore the efficacy of the fortune-teller first-hand; or Faust’s tryout may have been just a whim intended to break up the day’s routine.)

How talented was Faust? Well, after a few pitches from Faust (who was still in his street clothes), McGraw ditched his glove and caught his offerings barehanded (most likely to embarrass and discourage the eager, but inadequate, hurler).

“His windup was like a windmill. Both arms went around in circles for quite a while before Charlie finally let go of the ball. Well, regardless of the sign that McGraw would give, the ball would come up just the same. There was no difference in his pitches whatsoever. And there was no speed – probably enough to break a plane of glass, but that was about all.”

NY Giants’ CF Fred Snodgrass, describing Charlie Faust’s tryout deliveries in Lawrence S. Ritters’s book “The Glory of Their Times – The Story of the Early Days of Baseball told by the Men Who Played it.”

When McGraw’s bare-handed catching didn’t diminish Faust’s confidence, the manager tried another tack. He told Faust to take a few batting practice swings. Faust swung and missed a few lollipop offerings, before finally making weak contact. With that contact, McGraw urged Faust to run around the bases – sliding into each one, tattering his Sunday-best clothes, picking up a few scrapes, but (apparently) not bruising his ego or dampening his conviction.

Well, as one might expect, McGraw send the Faust on his way without a contract. The Giants, however, won big that day and when the still undaunted Faust showed up at the park the next day, the players reportedly put him in a spare uniform and sent him on out for another pre-game exhibition of his “skills” (most likely for their own amusement). The ensuing laughter did not embarrass the affable Faust. Rather he liked the attention and felt he had made a step forward in his quest. That day, with Faust as the pre-game show, the Giants again topped the Cardinals and the following day, they enjoyed a repeat performance from Faust and another victory. A pattern was developing.

The next day, as the team left Saint Louis, the fun (at least for McGraw) was over and the team unceremoniously ditched the gullible Faust at the railroad station. Two similar stories are reported here, both have the team sending him back to the team’s hotel on a fool’s errand – to retrieve either his contract or his train ticket. (Neither, of course, existed. The Giants, without Faust as a good luck charm, lost four of the next six games and were again seeming more like a third- or fourth-place squad than a pennant contender.

When the team returned home to New York, who should be waiting for them but Faust, as enthusiastic as ever about his role as the key to the Giants’ championship. The ballplayers – and McGraw – again, being a generally superstitious bunch, were receptive to Faust rejoining the squad. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Faust stayed with the team and became a popular source of pregame entertainment for fans. He would warm up, take batting practice, shag flies and run the bases – at which times his awkward, but energetic, displays would delight the fans (and sports reporters). Even opposing players would get into the act, sometime hitting against Faust in their own batting practices and “striking out” against his soft tosses. There was some less than good natured laughter, but Faust did not seem to notice; relishing his spot on the squad and warming up in the bullpen nearly every game – so he would be ready when he was needed on the mound. (The story goes that when the Giants would fall behind, McGraw would have Faust warmup in the bullpen – and, inevitably, the Giants would rally.) Faust was fast-becoming the toast of the town.

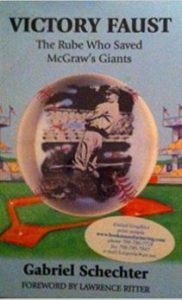

Faust, indeed, also proved a good luck charm for the New York squad – some speculated just by keeping the team happy and “loose.” One thing is clear, his conviction that he and the Giants were headed for greatness was unshakeable – and perhaps contagious. As Gabriel Schechter author of the book “Victory Faust – The Rube Who Save McGraw’s Giants” reports, as the season went on, the team went 36-2 when Faust was with them and just 3-7 when he wasn’t. (A bit of explanation on at least some those absences: Faust became so popular in New York that he was offered a job on vaudeville, telling stories, duplicating his windup and imitating the stars of the game. In his first three days in show business, the Giants went without a win, and Faust returned to his team and what he saw as his true destiny.)

Still Faust was not satisfied and kept badgering McGraw to give him a chance to toe the rubber in a game.

On October 5, the Giants clinched the pennant, but they still had a week’s worth of meaningless games until the fortune teller-predicted and Faust-promised World Series. And, Faust was still driven to appear on the mound. He had not – as predicted – “pitched” the Giants to success. He was about to get his wish.

On October 7, McGraw relented to Faust’s consistent badgering and brought him in to pitch the ninth inning of a game in which the Giants trailed the Boston Rustlers (Braves) 4-2. Faust, throwing fat pitches out of his exaggerated windmill-style windup actually managed to get out of the inning giving up just one run on one-hit (a double) and a sacrifice fly.

In the bottom of the ninth, the Giants made the final out with Faust on deck. But Faust, still showing his unbridled (perhaps slightly off-kilter) enthusiasm took his place in the batters’ box and refused to leave the field. And then a strange thing happened. The Boston players “played” along, stayed on the field and pitched to Faust. When he tapped a ball to the infield, the Boston players mishandled each throw and tag attempt until finally retiring a clumsily sliding (but surely smiling) Faust about ten feet from home plate. Although the at bat didn’t count, Faust had made his (and the fortune-teller’s) dream come true – he had pitched in a major league game. But he wasn’t done yet.

On October 12, in the final inning of the Giants’ final regular season game, with New York trailing the Brooklyn Superbas (Dodgers) 5-1, Faust pitched again – notching a scoreless frame. This time, he came to the plate when it counted And, like their Boston counterparts, the Brooklyn squad played along. Apparently believing there was little chance the awkward Faust could be counted on to hit the ball, Brooklyn pitcher Eddie Dent “dented” Faust with a pitch. Faust then, being largely ignored (or, perhaps, even encouraged) by the Brooklyn team, stole second and third base before scoring on a groundout. Quite an end to the season, and the World Series was ahead. It was also quite the end to Faust’s major league career.

Despite Faust’s presence, the Giants lost the World Series to the Philadelphia Athletics four games to two – and McGraw seemed to lose interest in the New York’s good luck charm.

The Giants did not invite Faust back in 1912 – but, no surprise, he showed up anyway. And, in a tribute to persistence, was again allowed to provide pre-game hijinks at the Polo Grounds (the team declined to pay his travel expenses for away games that season). Although the Giants (who would have expected otherwise) got off to a 54-11 start, McGraw had tired of Faust’s continued badgering about the opportunity to take the mound – and Faust was convinced to leave the team in mid-season.

The Giants won more than 80 percent of the games they played while Faust was with the team.

Faust moved back to Kansas, then California (perhaps, looking for Lulu) and eventually to Seattle (near one of his brothers) still insisting he would make it back to help the Giants win another pennant. It was not meant to be. In December of 1914, Faust was committed to an Oregon mental hospital, where he was diagnosed with dementia and (after several weeks of treatment) released in his brother’s care. Faust died June 18, 1915 (at age 34) of tuberculosis. Often described a “delusional,” the fact is Charles “Victory” Faust made it to the big leagues and did earn a pair of turns on the mound for a pennant winning club. In doing so, he carved a spot for himself as one of the more memorable characters in baseball history – and realized a dream that lives in most baseball fans’ hearts.

In 1915, the year Charles “Victory” Faust passed away, the New York Giants finished last in the National League – their first last-place finish since 1900. It would, in fact, be their only last place finish between 1900 and 1943.

Charles “Victory’ Faust – MLB Record

Pitching:

Games … 2. W-L … 0-0. Innings pitched … 2. Hits … 2. Earned runs … 1. ERA … 4.50.

Hitting

Plate appearances … 1. At Bats … 0. Hits … 0. Walks … o. Hit By Pitch … 1. Stolen bases … 2. Runs scored … 1. RBI … 0.

A final note: You can probably file this one under #HowTheGameHasChanged. There will never be another player like Charles “Victory” Faust.

Primary Resources; Charlie Faust – Society for American Baseball Research Biography, by Gabriel Schechter; Searching for Victory – The Story of Charles Victor(y) Faust, by Thomas S, Busch, Society for American Baseball Research, Research Journals Archives; Baseball-Reference.com; The Glory of Their Times, by Lawrence S. Ritter, McMillian and Company (1966).

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.