It’s the off-season and, as usual, while I await the start of Spring Training, I find myself musing about a variety of baseball topics and statistics. This time, it’s brief – very brief – pitching appearances. So, while this post my seem, at times, a bit like watching a series of unrelated slides (some or you do remember slides, I hope), there is a central theme.

One first observation, as I looked at the leading pitchers when it comes to brief appearances (I chose one-batter and one-pitch mound appearances), it was clear the lists was dominated by left-handed sidearmers – with offerings ranging submariner Mike Myers’ angling fastball to Tony Fossas’ slow, sidearm curve.

How dominant were lefty sidearmers on these lists? When you look at the top five pitchers in terms of one-batter and one-pitch appearances, seven pitchers hold the top ten places (three appear on both lists). All seven are southpaws and five of the seven are sidearmers or submariners. This portside dominance, by the way, has been recognized with an adaption of the term “LOOGY” to describe a “Left-handed One Out Guy.” With recent rule changes, however, this terminology may be on the way to becoming extinct. (More on that a bit later).

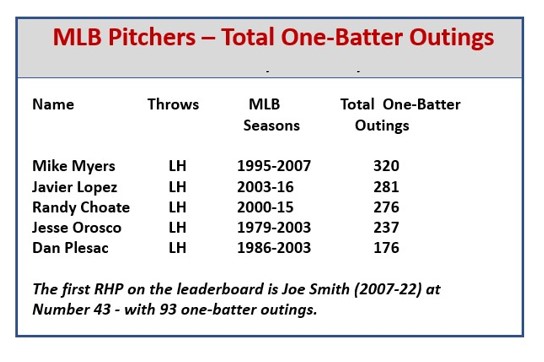

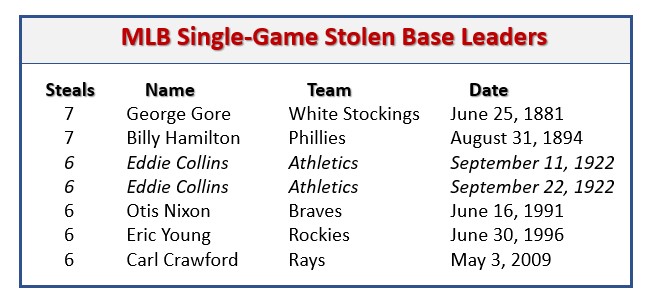

Let’s get on to the lists – starting with the one-batter appearances.

Photo: Keith Allison on Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The career leader in one-batter appearances is submariner Mike Myers – with 320 one-batter appearances in 13 MLB seasons (1995-2007 … Marlins, Tigers, Brewers, Rockies, Diamondbacks, Mariners, Red Sox, Yankees, White Sox). Myers was signed by the Giants in the fourth round of the 1990 MLB Draft – out of Iowa State University, where he went 6-5, 2.65 over two seasons (14 games as a starter/18 as a reliever).

Myers credits Hall of Famer Al Kaline with encouraging him (in 1996, Myers’ seventh pro season and second in the major leagues) to “drop down” into the submarine motion. Myers went on to pitch in the majors through 2007 – going 25-24, 4.29 with 14 saves. His status as one of the kings of the brief appearance is reflected in the fact that he threw a total of 541 2/3 innings in 883 MLB appearances (0.61 innings per appearance – all in relief) – walking 256 and fanning 429. He averaged just 41.6 innings per season over his MLB career and pitched 50 or more innings in only four campaigns (a high of 64 1/3 innings in 83 1996 appearances). Myers twice led the AL in appearances and made 60 or more appearances in 12 seasons. Over his MLB career, Myers held left-handed batters (1,263 plate appearances) to a .219 average, while righties (1,122 plate appearances) hit .301 against him. Myers’ best season was 2000, when he went 0-1, with a 1.99 earned run average and one save in 78 games (45 1/3 innings) for the Rockies. Notably, that season, Myers put up a 2.00 ERA at hitter-friendly Coors Field.

Mikey Myers led the American League in pitching appearances in 1996 and 1997 (83 and 85 games, respectively). In each of those seasons, his earned run average was north of 5.00 (.5.01 and 5.70).

Note: In the chart above, all are southpaws and all but Dan Plesac were submariners or sidearmers.

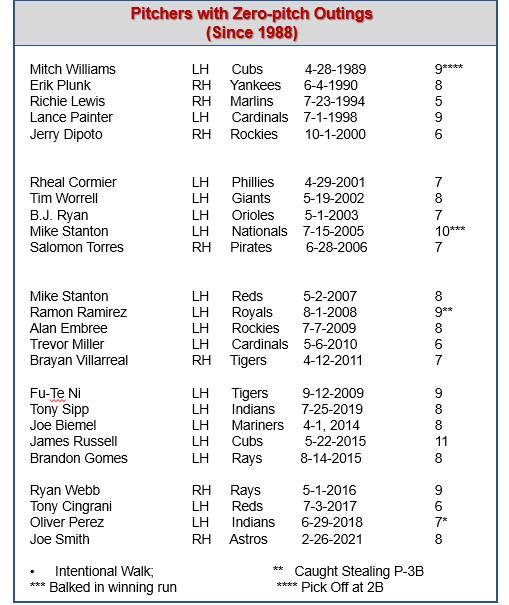

Now, the one-pitch appearances.

Javier Lopez is the King of the One-Pitch Outing – and is likely to retain the crown.

DISCLAIMER, KIND OF

MLB didn’t start tracking pitch counts until 1988, so the one-pitch inning records noted here – unless otherwise explained – are from 1988 forward.

Photo: Lopez SD Dirk on Flickr, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Javier Lopez was a left-handed, sidearming relief specialist who forged a 14-season MLB career (2003-2016 … Rockies, Diamondbacks, Red Sox, Pirates, Giants). Lopez’ MLB tenure took place after MLB started tracking pitch counts and before the 2020 rule requiring a relief pitcher to face three batters or finish a half inning (except in cases of injury or illness.). In his career, Lopez made 839 appearances (no starts) and averaged about 2/3 of an inning (0.64 innings) and 2.7 batters faced per appearance. He was the king of the one-pitch appearance. During his career, he came into a game, tossed one pitch a record 34 times and was done for the day (six times in 2015 alone).

In 281 (33.5 percent) of his MLB appearances, Javier Lopez faced just one batter.

Now, you might think that most of one-pitch those appearances ended an inning. Nope. In fact, only 14 of those 34 appearances involved Lopez recording the final out of the frame. Under current rules, Lopez would have had to remain in the game in twenty of his one-pitch appearances – which is why I’m pretty sure he will remain king of the one-pitch inning.

In his 34 one-pitch outings, Lopez held hitters to a .206 average. He gave up f0ur singles. two doubles and one home run and induced 19 ground outs (three double plays), five fly outs and one pop out (two batters were safe on infield errors.)

Note: On the chart above, all are southpaws and all but Mike Stanton are sidearmers.

Lopez was signed by the Diamondbacks out of the fourth round of the 1998 MLB draft. He played his college ball at the University of Virginia, where he was primarily used as a staring pitcher. He began his professional career as a starter, but struggled in that role and was converted to a reliever in his fourth season (2001). He made his MLB debut with the Rockies in 2003 and went 4-1, 3.70, with one save in 75 appearances (58 1/3 innings), walking 12 and fanning 40. He went on to pitch in 14 MLB seasons (2003-16 … Rockies, Diamondbacks, Red Sox, Pirates, Giants), going 30-17, 3.48 with 14 saves and 533 1/3 innings pitched (358 strikeouts) in 839 appearances (all in relief). He did his best work with the Giants, going 17-8, 2.47, with ten saves over seven seasons (2010-16). Lopez held lefties to a to a .202 average (1,242 plate appearances) versus .297 for right-handers (1,031 plate appearances).

One Thing Leads to Another …

Looking at the Impact of the Three-Batter Rule

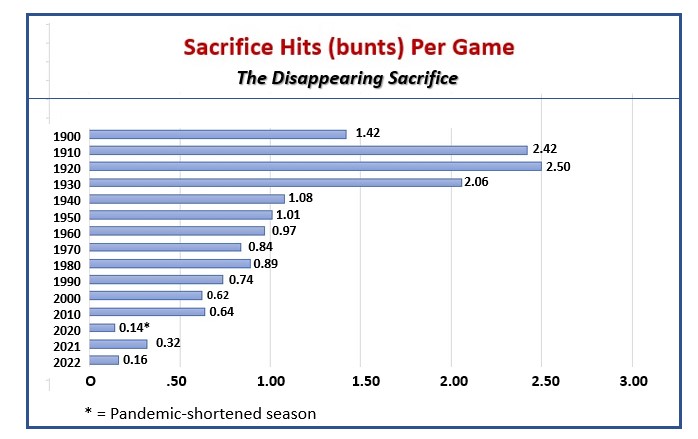

If you are wondering, like the Roundtable was, how much the 2020 rule requiring relievers to pitch to “three-batters or end of an inning” altered pitching strategies, here are some stats. In 2019, there were 1,100 instances in which a pitcher faced just one batter in an appearance and 110 in which that pitcher tossed just one pitch. (There were also nine instances in which a pitcher was not credited with a batter faced in an appearance, usually involving a pick off or caught stealing). In 2021, the first full season with the new rule, there were 660 one-batter appearances (a 40 percent drop), 64 one-pitch appearances (a 42 percent drop) and 13 zero-batters-faced appearances

Special Mention … Jesse Orosco

Jesse Orosco ranks fourth on he list of one-batter appearances and second on the roster of one-pitch appearances (keep in mind that pitch count tracking did not really became a “thing” until Orosco’s ninth MLB season.)

Jesse Orosco ranks fourth on he list of one-batter appearances and second on the roster of one-pitch appearances (keep in mind that pitch count tracking did not really became a “thing” until Orosco’s ninth MLB season.)

Orosco was signed out of the second round of the 1978 MLB Draft by the Twins. He played college baseball for Santa Barbara City College (1978), where he won All-Western State Conference honors. In 1979, after one solid rookie-level seasons (4-4, 1.12, with six saves in 20 appearances), the Twins sent Orosco to the Mets in the trade that brought Jerry Koosman to Minnesota,

Orosco went on to a 24-season MLB career (1979, 1981-2003 … Mets, Dodgers, Indians, Brewers, Orioles, Cardinals, Padres, Yankees, Twins).

While he never led his league in appearances, Jesse Orosco holds the all-time MLB record for regular -season mound appearances with 1,252.

Orosco, a two-time All Star went 87-80, 3.16, with 144 save in 1,252 appearances (four starts). He pitched 1,295 1/3 MLB innings, walking 581 and fanning 1,179, He averaged 1.03 innings per appearance. Orosco’s best season was 1983 (Mets), when he went 13-7, 1,47, with 17 saves in 62 appearances (110 innings).

How About a Two-Fer … or Twelve Can Be A Lucky Number

On July 31, 1983, the Mets and Pirates faced off in a doubleheader (Remember those?) in New York. Both games went twelve innings and the Mets’ Jesse Orosco earned both victories. In the first game, Orosco pitched four scoreless frames (innings nine through twelve) and picked the win as the Mets triumphed 7-6. In Game Two, he came on in the top of the twelfth in a scoreless game, pitched a scoreless inning and picked up his second win of the day, as the Mets tallied a run in the bottom of the inning.

Orosco is somewhat unique on these lists of brief appearances in that: 1) his career began before the LOOGY became a thing; and 2) he was pretty much a full-time closer until 1987. From 1979 through 1987, Orosco went 47-47, 2.73 with 107 saves. He pitched 595 2/3 innings in 372 games (1.60 innings per game). Then, from 1991 through 2003, he went 40-33, 3.52 with 37 saves – logging 699 2/3 innings in 880 appearances (0.80 innings per game). In the eight seasons from 1979 through 1987, Orosco logged 25 one-batter appearances (6.6 percent of his total appearances), while in 16 campaigns from 1991 through 2003, he notched 212 one-batter appearances (25.7 percent of his total appearances).

___________________________________________

More of Baseball Roundtable “One Thing Leads to Another”

On July 22, 1986, southpaw Jesse Orosco was involved in an unusual set of pitching changes.

- With the Mets and Reds tied 3-3 in Cincinnati, Mets’ manager Davey Johnson brought Orosco to the mound to open the bottom of the tenth, replacing Rick Aguilera. Orosco was the Mets’ fifth pitcher to take the mound in the game. Aguilera, however, was not one of them. Aguilera had been used as a pinch hitter for pitcher Doug Sisk (batting sixth) in the top of the inning.

- In the bottom of the tenth, Orosco struck out Reds’ RF Dave Parker, gave up a single to PH Pete Rose and fanned CF Eddie Milner (while Eric Davis, who had come in to run for Rose, stole second and third).

- With right-handed hitting SS Wade Rowdon coming up (and a runner on third), Johnson brought righty Roger McDowell to the mound. He didn’t, however, pull Orosco from the game. Rather , Johnson made a number moves and substitutions that ended up with Orosco playing right field – and new players at C and 3B. It all worked out, as McDowell got Rowdon to ground out to end the inning.

- McDowell faced the first three batters in the bottom of the 11th and, with a runner on second and two out, Reds’ left-swinging outfielder Max Venable was due up. Johnson brought Orosco back to the mound, but didn’t take McDowell out of the game. Instead, McDowell moved to RF – and Orosco fanned Venable.

- Orosco pitched a scoreless twelfth frame and, when the 13th inning opened, McDowell (who by this time was playing left field) came back to the mound, with Orosco going back to RF and Mookie Wilson, by then playing RF, moved to LF. McDowell pitched the 13th and 14th frames (with Orosco in RF), before the Mets eventually won 6-3 by virtue of a 14th inning three-run home run by Howard Johnson.

In the game, the Mets used 21 players, with five pitchers taking the mound – and and five different players manning RF, three playing LF and two different players each used at C, 3B, and SS.

_______________________________________________

Moving right along, how about a look at a couple of pitchers who got the maximum “Output” from a single pitch?

Three-for-One … With a Little Help from My Friends

While this occurred before MLB began tracking pitch counts, it is well documented enough to be included here. On July 27, 1930, the Reds’ righty Ken Ash – recorded three outs and picked up a victory, while throwing just one pitch. Notably, Ash got a little help from the Cubs’ base-running foibles.

Ash came on in the bottom of the sixth with: the Cubs leading the Reds 3-2 (two runs had already scored in the inning); runners on first and third (Cubs’ LF Danny Taylor on first, CF Hack Wilson on third); no outs; and 1B Charlie Grimm at the plate. Grimm hit ground ball to Cubs’ 2B Clarence Blair, and Wilson made the mistake of breaking for home. Blair threw behind Wilson to 3B Tony Cuccinello, who threw to C Clyde Sukeforth, who tagged out Wilson for the first out. Grimm, meanwhile, rounded first and decided to try for second on the play, but Taylor was still on the second base bag. So, Grimm reversed direction and headed back toward first, Sukeforth threw to 1B Joe Stripp, who tagged Grimm for out number two. As the play at first unfolded, Taylor took off for third and Stripp threw to Cuccinello for the third out. Ash was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the sixth, as the Reds scored four runs to take a lead they would not relinquish – giving Ash the victory.,

Ash would finish the season 2-0, 3.43 (one save) in 16 appearances. Ash played in just four MLB seasons (1925, 1928-30 … White Sox, Reds), going 6-8, 4.96 with three saves in 55 games (13 starts).

Lucy Number 13

On July 13, 1995, the Mariners’ RHP Jeff Nelson also got the most out of a one-pitch mound appearance, at least in terms of outs. Nelson came on in relief of Tim Belcher, with the Mariners trailing the Blue Jays 4-1, with two runners on base (Blue Jays’ RF Shawn Green at second and SS Alex Gonzalez at first). On Nelson’s first pitch to Sandy Martinez, the Jays’ catcher popped a bunt toward the mound. Nelson let the ball drop, then picked it up and fired to SS Luis Sojo covering second. Sojo tagged Green (still on the bag, but forced to go to third) for the first out. Sojo then touched the second base bag forcing Gonzalez; and then fired to 1B Tino Martinez to retire Sandy Martinez.

Note: Some smart fielding on this play. 1) Nelson letting the popped up bunt drop; and 2) Sojo knowing to tag Green before touching the second base bag. Had he stepped on the bag first, Gonzalez would have been out and Green, no longer forced to go to third, would have been safe on second. .

Nelson pitched in 15 MLB seasons (1992-2006 … Mariners, Yankees, Rangers, White Sox), going 48-45, 3.41, with 33 saves in 798 appearances (all in relief).

How About Zero-Pitch Appearances?

Well, as usual with Baseball Roundtable, one thing again led to another, and after looking into one-batter and one-pitch appearances, I began digging into zero-pitch appearances.

Since 1988, there have been two dozen official pitching appearances of zero pitches. As the chart below shows, southpaws again dominate this brief outing category, holding 19 0f 24 spots. Note: In this chart, these outings – unless otherwise noted – consisted of a pick-off (and in, some cases rundown) at first base.

A handful of these zero-pitch outings captured my attention.

Two of those zero-pitch outings actually resulted in a win for the hurler in question.

All in a Day’s Work

On May 1, 2003, Orioles’ southpaw reliever B.J. Ryan was called in from the bullpen, with the Orioles’ trailing the Tigers 2-1 (in Detroit). Tigers’ SS Omar Infante was on first, with two out and RF Bobby Higginson (batting third in the order) at the plate. Before sending a pitch to the plate, Ryan sent a pick-off throw to 1B Jeff Conine. Infante was eventually retired on the play (pitcher – to first – to shortstop), ending the inning. The Orioles then came back to take a 3-2 lead in the top of the eighth. Buddy Groom relieved Ryan (now the pitcher of record) in the bottom of the inning, the Orioles held their lead and Ryan got a win … without ever throwing a pitch.

Ryan pitched in 11 MLB seasons (1999-2009) and went 21-28, 3.37, with 117 saves in 560 games. The two-time all Star’s best season was 2006 (Blue Jays), when he went 2-2, 1.37, with 38 saves.

This Could be the Last Time

On July 7, 2009, Rockies’ southpaw Alan Embree notched a zero-pitch win. This one caught the Roundtable’s attention because it was the final win of the 39-year-old Embree’s 16-season MLB career. In the top of the eighth, with the Rockies and Nationals tied at four apiece, Embree was summoned to the mound with two outs and a runner on first (PH Austin Kearns). Before throwing a pitch, Embree picked off Kearns on a play that went Embree to 1B Todd Helton to SS Troy Tulowitzki back to Embree. The Rockies scored in the bottom of the inning to take a 5-4 lead, closer Huston Street replaced Embree (who had been pinch hit for) and saved the game – and the win – for Embree. So Embree, while not tossing a pitch got a win, an assist and a putout.

Embree went 39-45, 4.59, with 25 saves in a 16-season MLB career (1992, 1995-2009 … Indians, Braves, Diamondbacks, Giants, White Sox, Padres, Red Sox, Yankees, A’s, Rockies). Notably., 17 of his 25 career saves came for the 2007 A’s.

Put A Bow on It

Let’s Wrap this Whole Thing up

On October 1, 2000, Rockies’ righty Jerry Dipoto was called to the mound for the final time in his eight-season MLB career. It was the bottom of the sixth and Dipoto’s Rockies were trailing the Braves 5-3 (three runs had scored in the inning). Braves’ LF Reggie Sanders was on first, there were two outs and RF Brian Jordan was at the plate. Before tossing a pitch Dipoto picked Sanders off first, ending the inning. So, in his last MLB appearance, Dipoto – while recording 1/3 of an inning pitched – did not actually pitch at all.

Save The Last Out for Me

Cubs’ southpaw Mitch Williams recorded the only zero-pitch save (since 1988). It happened at Wrigley Field on April 28, 1989. In that game, Williams was called in to relieve Cubs’ starter Paul Kilgus, with two outs in the ninth and the Cubs on top of the Padres 3-1. At the time, the Padres had scored once in the inning and had runners on first (RF Luis Salazar) and second (LF Carmelo Martin). Before tossing a pitch to Padres’ SS Gary Templeton, Williams picked Salazar off second (Williams to SS Shawn Dunston), earning a zero-pitch save.

Cubs’ southpaw Mitch Williams recorded the only zero-pitch save (since 1988). It happened at Wrigley Field on April 28, 1989. In that game, Williams was called in to relieve Cubs’ starter Paul Kilgus, with two outs in the ninth and the Cubs on top of the Padres 3-1. At the time, the Padres had scored once in the inning and had runners on first (RF Luis Salazar) and second (LF Carmelo Martin). Before tossing a pitch to Padres’ SS Gary Templeton, Williams picked Salazar off second (Williams to SS Shawn Dunston), earning a zero-pitch save.

Williams, a one-time All Star, pitched in 11 MLB seasons – going 45-58, 3.65 with 192 saves in 619 games. He saved 30 or more games in three seasons. 1989, the year of his zero-pitch save, was Williams All-Star season. He went 4-4, 2.76, with 36 saves and led the league in appearances with 76.

In 1980, Mitch Williams – as a 21-year-old rookie with the Rangers – led the AL in appearances with 80 and went 8-6, 3.58 with eight saves. Despite that performance, he did not receive a single vote in the Rookie of the Year balloting(won by the Indians Joe Charboneau).

Not a Lucky Break

Not a Great Finish

On July 15, 2005, Mike Stanton of the Nationals was called into a game in a tough spot. It was the bottom of the tenth inning, the Nationals and Brewers were tied at 3-3 and the Brewers had runners on first and third with one out when Stanton came to the mound to take over from Luis Ayala. Conventional wisdom? Intentionally walk 1B Lyle Overbay to load the bases and set up a possible double play. Unconventional outcome? The game resumed after Stanton’s warm-ups and, before tossing a pitch, Stanton balked in the winning run. Game over, without Stanton throwing a single pitch.

Stanton pitched 19 years in the major leagues (1989-2007 … Braves, Yankees, Red Sox, Mets, Nationals, Giants, Ranger, Reds), He appeared in 1,178 games, picking up 69 wins (63 losses), with 84 saves and a 3.92 ERA. In 1993, he saved 27 games for the NL West-leading Atlanta Braves.

Mike Stanton appeared in 53 post-season games, going 5-2, 1.54, with one save over 22 2/3 innings, with 21 walks (nine intentional) and 47 strikeouts.

Now that Doesn’t Seem Fair

On June 29, 2018, Indians’ southpaw Oliver Perez became the first pitcher credited with allowing a baserunner, in a game in which he didn’t throw a single pitch. Perez was brought into the game in the seventh inning, with two outs, runners on second and third and the Indians trailing the A’s 2-0. A’s leadoff hitter and CF, left-handed swinging Dustin Fowler, was scheduled to bat. A’s Manager Bob Melvin sent in right-handed swinging Matt Canha to pinch hit for Fowler and Indians’ manager Terry Francona chose to intentionally walk him. No pitches thrown under the relatively new “wave ‘em to first” rule, but the walk and baserunner were charged to Perez. Right-handed hitting Chad Pinder came in to pinch hit for lefty-swinging Matt Joyce and Francona countered with right-hander Zack McAllister. Perez left the mound after allowing a baserunner via a walk, without ever tossing a pitch in the contest. Fortunately, McAllister fanned Pinder on four pitchers and Perez was off the hook.

Perez, still active in 2022, has pitched in 20 MLB seasons (2002-2010, 2012-2022), going 74-94, 4.37, with five saves in 703 games (195 starts).

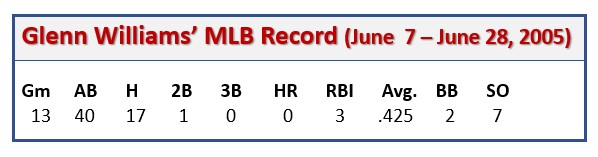

Roundtable Extra … A Brief Outing That Lasted an Entire Career

Larry Yount, brother of Hall of Famer Robin Yount, made his MLB debut on September 15, 1971 – coming on in the top of the ninth to replace Skip Guinn (who had been pinch hit for in the previous half inning). The score was 4-1 and, if all worked out, Yount would face LF Ralph Garr, 1B Hank Aaron and C Earl Williams. All did not work out. Yount had experienced some elbow pain in the bullpen warming up and, as he continued to warm up on the mound, it only got worse. He called the trainer to the mound and, after a bit of discussion, Yount walked off the field – officially registering an MLB appearance, but not tossing a single pitch. Yount pitched two more season in the minors, but never came to the major-league mound again. Note: This was before the pitch-tracking era began, but has between widely enough reported to earn its spot.

Primary Resources: Baseball-Reference.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

Baseball Roundtable – Blogging Baseball Since 2012.

Baseball Roundtable is on the Feedspot list of the Top 100 Baseball Blogs. To see the full list, click here.

Baseball Roundtable is on the Feedspot list of the Top 100 Baseball Blogs. To see the full list, click here.

Baseball Roundtable is also on the Anytime Baseball Supply Top 66 Baseball Sites list. For the full list, click here.

I tweet (on X) baseball @DavidBaseballRT

Follow Baseball Roundtable’s Facebook Page here. More baseball commentary; blog post notifications.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research (SABR); Negro Leagues Baseball Museum; The Baseball Reliquary.