Photo by candyschwartz

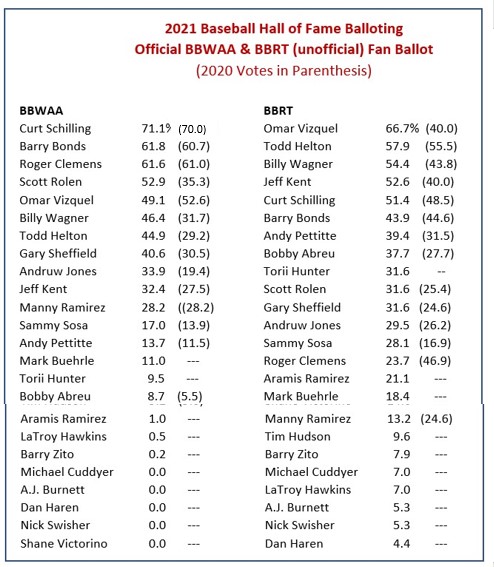

The official 2021 Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) Hall of Fame balloting results are in – and for the first time since 2013, there were no electees. The top five vote getters were Curt Schilling (71.1%), Barry Bonds (61.8%), Roger Clemens (61.0%), Scott Rolen (52.9%) and Omar Vizquel (49.1%). That differs significantly from the unofficial ballots cast by 114 Baseball Roundtable readers. While, like the BBWAA, the fan voters gave no player the needed 75 percent for election, the leading votegetter list differed significantly. BBRT readers placed Omar Vizquel (66.7%), Todd Helton (55.5%), Billy Wagner (43.8%), Jeff Kent (52.6 %) and Curt Schilling (51.4%) in their top five. Here’s a vote percentage comparison.

Blank Ballots

There was some online discussion over the past few days surrounding the blank ballots turned in by Ron Cook of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who (in a column) cited an aversion to “cheapening the Hall” and consideration of the “character clause” among the reasons for his blank ballot. Nick Canepa of the San Diego Union-Tribune cited similar reasons (also in a column), indicating he saw no one the ballot in his “legitimacy range as ballotworthy” and that he was also influenced by the PED controversy. (“You have to be a dominant non-juicing stud to get my vote,” Canepa wrote.) I expect those same reasons were behind the three blank ballots received in the BBRT fan voting. Notably, Cook and Canepa were not the only writers submitting a blank ballot. A record 14 blank ballots were submitted – that comes to 3.5 percent of the total, fairly comparable to the BBRT’s fan balloting level of 2.6 percent.

I found a couple of odd occurrences as I compared the BBWAA and BBRT vote counts. In 2020, Omar Vizquel garnered considerably more support from the writers than he did in the BBRT fan ballot (52.6% from the BBWAA/40.0% in the BBRT fan ballot). This year, that turned around, with Vizquel jumping to 66.7 percent in the BBRT ballot, but dropping to 40.5% in the official BBWAA ballot. (Domestic abuse allegations, which Vizquel had denied, may have influenced some BBWAA votes. Those allegations garnered considerable media attention in mid-December, about halfway through the BBRT voting period.)

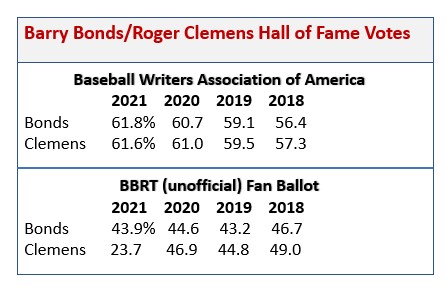

Then, there is Roger Clemens. Clemens and Barry Bonds, as the chart below shows, have tracked fairly closely in recent BBWAA and BBRT balloting. That remained fairly consistent for the BBWAA this season, but on the BBRT unofficial fan ballot, Clemens dropped from 46.9% to 23.7%. I really can’t figure that one out.

Here are a few additional observations/comparisons:

- While the fans were tougher on Schilling, Bonds and Clemens than the writers, they were more generous “down the ballot.” In the BBRT fan ballot, not a single player was shutout and only one player received less than 5 percent – the figure needed to stay on the BBWAA official ballot. (See the “From the Heart Cadre” near the end of this post for a possible explanation.) The BBWAA balloting saw five players shutout and eight players below 5 percent.

- The biggest gainer in the BBWAA voting was Scott Rolen, who made a 17.6 percentage point jump – from 35.3% to 52.9%. The biggest gainer on the Baseball Roundtable fan ballot was Omar Vizquel, who made a 26.7 percentage point leap from last year (40.0% to 66.7%). Other big gainers on the BBWAA ballot were: Todd Helton – up 15.7 pct. points (29.2 to 44.9); Billy Wagner – up 14.7 (31.7 to 46.4); Andruw Jones – up 14.5 (19.4 to 33.9); and Gary Sheffield – up 10.1 (30.5 to 40.6). Additional big gainers on the BBRT fan ballot were: Jeff Kent – up 12.6 (40.0 to 52.6); Billy Wagner – up 10.6 (43.8 to 54.4); and Bobby Abreu – up 10.0 (27.7 to 37.7).

- Only two holdovers on the BBWAA ballot saw a decline in support – Omar Vizquel and Tim Hudson. Three players saw a decline in support on the BBRT ballot – Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds and Manny Ramirez.

- The first-timer receiving the most support on the BBWAA ballot was Mark Buehrle with 11.0%. On the BBRT fan ballot, that distinction went to Torii Hunter with 31.6%. BBRT has a notable following among the Halsey Hall (MN) Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research which may provide insight into Hunter’s popularity in the BBRT vote. On the BBWAA ballot, Hunter did get the second-most votes among first-timers (9.5%).

- A few other notable differences: Roger Clemens ranked third on the BBWAA ballot, 14th on the BBRT ballot; Bobby Abreu ranked 16th on the BBWAA ballot, eighth by BBRT voters; Jeff Kent was ranked tenth by the BBWAA voters, fourth on the unofficial BBRT ballot.

- In 2022, the following players (their 2021 voting percentages in parenthesis) will be in their final year on the ballot: Roger Clemens (61.0%); Barry Bonds (60.7%); Sammy Sosa (13.9%). Curt Schilling, who would be in his tenth and final year, has asked to be removed from the ballot.

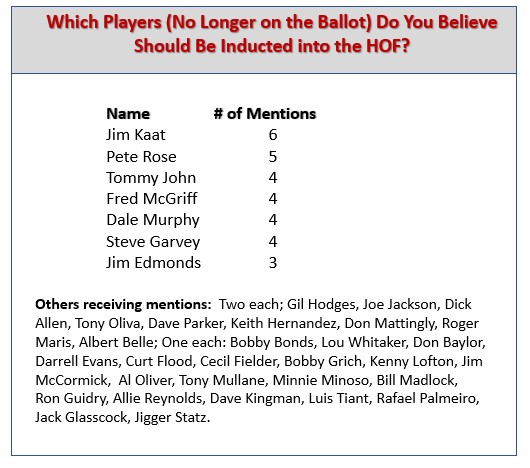

Forty-five BBRT survey respondents answered the question regarding which players not currently in the Hall of Fame (and not on the ballot) should be in the Hall. Jim Kaat led the way with six mentions (13.3%0, followed by Pete Rose with five. Below is the full list.

—-Hall of Fame Voting Cadre—-

I’ll finish up with a review (yes, I’ve posted these before) of Hall of Fame voting cadres I have observed over the years. This, by the way, is not a judgement on voter strategies, but rather just an observation on factors that appear to have had a current or past influence on voting patterns and vote totals.

The Anti-PED Cadre

This group declines to vote for those who appear to be tied into the PED controversy (whether verified or suspected). There continues to be enough of these voters to effectively block a significant number of PED-associated candidates from election. In recent years, this cadre has made its presence felt in both the BBWAA and BBRT balloting. There does seem to be a slowly diminishing effect among BBWAA voters, but the impact on BBRT fan ballot total has been relatively stable.

The Character Cadre

Closely tied to the PED-Cadre, this group looks to the Hall of Fame official voting guidelines that call for consideration not just of performance and contribution to the team, but also “integrity, sportsmanship, and character.” A player’s attitude, political views and lifestyle, do appear to impact a number of voters’ preferences.

The Small Hall Cadre

This cadre has focused on demanding particularly high standards for election to the Hall of Fame – and has voted vote for very few (sometimes even zero) candidates. This, by the way, is not a new approach (despite this year’s record 14 blank ballot). Back in 1988, for example, nine blank ballots were cast in the BBWAA voting. A Los Angeles Times article quoted New York Daily News reporter Phil Pepe (who sent in one of the nine blank ballots) as saying the Hall of Fame was “too crowded,” adding “I think to go in alongside Ruth, DiMaggio, Williams, Aaron, Cy Young, you have to be the cream of the cream. The more you erode the standards, the more the standards will be eroded.” This year (as noted earlier in this post), Ron Cook mirrored those sentiments, saying his blank ballot reflected a belief that “The Hall should be only for the truly greats.” (I should note that, in recent years, the “Small Hall” voting strategy seems to have been on the decline.)

The Unanimously Adverse Cadre

This cadre has been made up of voters who are opposed to (or uniquely demanding) of a unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame. The logic appears to have been “If Babe Ruth, Stan Musial, Willie Mays, Cy Young or (insert a legendary player of your choice) was not a unanimous selection, why should player “X” be?” Mariano Rivera’s recent unanimous selection and Derek Jeter’s close call seem to indicate this cadre’s days may be behind us. Still, even when this is only a cadre of one, it is effective.

The Ballot-Hierarchy Cadre

Over the years, members of this cadre have drawn a line between first-ballot and subsequent-ballot votes. The Ballot Hierarchy was a “thing” for a long time. In a 2013 column, ESPN’s Howard Bryant wrote: “I believe in the hierarchy of the ballot, that the first ballot is different than the second or the tenth, that there is a special prestige to a player being voted in the first time he is eligible.” The question for BBRT is, “Do voters just withhold that first-, second- or other-ballot vote, or does it go to another candidate who meets the hierarchy test?”

The Clock Is Ticking Cadre

This approach works to the benefit of players approaching their final year on the ballot. For example, 2020 electee Larry Walker’s final five years on the ballot saw his vote percentages go (in order) – 15.5, 21.9, 34.1, 54.5 and 76.6. His stats didn’t change over that time, but the clock on eligibility was ticking downward.

The Strategist Cadre

Somewhat related to the “Ballot Hierarchy” group – at least in impact – this group reasons that certain players are sure bets to get the required 75 percent and chooses not to add to the sure-thing margin, instead casting that vote for a player they find deserving further down the ballot. This approach may actually improve the chances of additional candidates. A subset of this group is those who note that certain players (in, for example, the 40 percent range), while NOT likely to reach 75 percent in a given year, ARE pretty much assured of adequate support to stay on the ballot. This subset withholds votes from those candidates and votes to protects those they would like to see on the ballot (but who are less “safe”).

The From-the-Heart Cadre

This group (which seemed to show up in the BBRT unofficial fan ballot more than in the BBWAA voting) casts votes for a specific player (or players) further “down the board” either as a “fan” statement or to ensure that player does not fall off the ballot (get less than five percent).

The Ten-Best Cadre

This group simply votes for whom they felt are the ten best players; regardless of the factors influencing any of the cadres already noted. (Well, in some cases it is the eight or nine candidates they feel are deserving.)

So, there’s BBRT’s look at the 2021 HOF election, as well as some observations of current and past voting strategies.

Coming Soon: Who’s Your Daddy? Lefty Grove Edition.

Primary Resources: Baseball-Reference.com; Baseball-Almanac.com; MLB.com; Why I’m Turning in a Blank Ballot, January 23, 2021,Ron Cook, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Bland baseball ballot: No deserving Hall of Fame Candidates this year, January 16, 2012, Nick Canepa, San Diego Union-Tribune; Blank Hall of Fame ballot serves as protest ... January 14, 1988; Associated Press; Drawing a blank on a HOF ballot … January 9, 2013; Howard Bryant, ESPN Senior Writer; espn.com; My crowded Hall of Fame ballot, with no regard for the ‘sacred place’ … January 20, 2018; Ken Davidoff; New York Post (nypost.com); Hall of Fame Roundtable: Should voters ‘game” the ballot to get more players in? … January 22, 2018; Matt Snyder; cbssports.com; It’s a Hall voter’s prerogative to change mind … January 25, 2018; Patrick Reusse; StarTribune.

Baseball Roundtable is on the Feedspot list of the Top 100 Baseball Blogs. To see the full list, click here.

Baseball Roundtable is on the Feedspot list of the Top 100 Baseball Blogs. To see the full list, click here.

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like Baseball Roundtable’s Facebook Page here. More baseball commentary; blog post notifications; PRIZES.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research (SABR); Negro Leagues Baseball Museum; The Baseball Reliquary.