Archives for September 2018

Joe Mauer’s Final Game

New York Yankees – Kings of the 100-Win Campaigns … and other 100-win tidbits

Yankee Stadium … 100-win seasons live here.

Photo by Steven Pisano

Yesterday, (September 30, 2018), the Yankees picked up their 100th win of the season becoming the third American League team to reach 100 victories this year (Red Sox – 107 wins/Astros 102, with one game to go). It was both the Yankees’ 20th 100-win season (extending their own recrord)and the first time we have seen three 100-win teams in one league.

We have seen three 100-win teams in a single season in the past (just n in the same league).

- 1942: Cardinals (106-48); Dodgers (104-50 wins); Yankees (103-51)

- 1977: Royals (102-60); Yankees (100-62); Phillies (101-61)

- 1998: Braves (106-56). Astros-NL (102-60); Yankees (114-48)

- 2002: Yankees (103-58); A’s (103-59); Braves (101-59)

- 2003: Braves (101-61); Giants (101-61); Yankees (101-61)

- 2107: Indians (102-60); Astros-AL (101-61); Dodgers (104-58).

So, looking at the seven seasons (including 2018) in which there have been three 100-win teams, the Yankees have been involved six times; Braves three times; and Astros three times.

____________________________________________

100-WINS- NO REWARD

What really struck BBRT were those eight instances when an MLB team notched 100 wins – and still didn’t get a whiff of the post-season. As yon might expect, they all occurred before the 1994 establishment of the Wild Card system. Let’s look at those:

- 1909 Chicago Cubs – 104-49 … finished second, 6 ½ games behind the Pirates

- 1942 Brooklyn Dodgers – 104-50 … finished second, two games behind the Cardinals

- 1954 Yankees – 103-51 … finished second, eight games back of the Indians

- 1961 Tigers – 101-61… finished second, eight games behind the Yankees

- 1962 Dodgers – 102-63 … finished second, one game back of the Giants

- 1980 Orioles – 100-62 …finished second, three games behind the Yankees

- 1993 giants – 103-58 … finished second, one game behind the Braves

______________________________________________________

In MLB history, 105 teams have put together seasons of at least 100 wins.

- No franchise has had more 100- win seasons than the Yankees with 20 (including 2018) … the only other franchise with at least ten 100-win campaigns is the Athletics (10).

- The National League leader is the Cardinals at nine.

- The Astros are the only franchise to deliver a 100-win season in both the American and National Leagues.

- Teams which have never had a 100-win season are the Rays; Blue Jays; Rangers; Brewers; Nationals; Marlins; Rockies; and Padres.

Three Straight 100-win Seasons

There have been just five runs of three-straight 100-win seasons in MLB history.

Philadelphia Athletics

- 1929 (104-46)

- 1930 (102-52)

- 1931 (102-52)

Saint Louis Cardinals

- 1942 (106-48)

- 1943 (105-49)

- 1944 (105-49)

Baltimore Orioles

- 1969 (109-53)

- 1970 (108-54)

- 1971 (101-57)

Atlanta Braves

- 1997 (101-61)

- 1998 (106-56_

- 1999 (103-59)

New York Yankees

- 2002 (103-58)

- 2003 (101-61)

- 2004 (101-61)

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Bell and Blyleven … Linked in MLB History

On this date (September 29) in 1986, Indians’ 2B Jay Bell and Twins’ pitcher Bert Blyleven crossed paths for the first time – and the encounter put both players into the MLB record books.

Bell was a 20-year-old rookie, playing his first MLB game and batting ninth. He was a September call up, after a .277-7-74 season at Double-A Waterbury of the Double A Eastern League. Blyleven was in his 17th MLB season, had already won 228 major league games – and was on his way to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It clearly looked like “advantage Blyleven.+

Bell’s first trip to the plate came with two outs in the top of the third inning. (Blyleven had retired the first eight Cleveland batters in order, fanning three.) On the future Hall of Famer’s first pitch to the rookie, Bell smacked a home run – tying an unbreakable MLB record (to date a total of 30 MLB players have homered on the first pitch they ever saw, Bell was just the twelfth to do so).

Bell’s first trip to the plate came with two outs in the top of the third inning. (Blyleven had retired the first eight Cleveland batters in order, fanning three.) On the future Hall of Famer’s first pitch to the rookie, Bell smacked a home run – tying an unbreakable MLB record (to date a total of 30 MLB players have homered on the first pitch they ever saw, Bell was just the twelfth to do so).

But the long ball had more significance. At the time of the at bat, Blyleven was tied with Hall of Famer Robin Roberts for the most home runs given up in a single season at 46. Bell’s round tripper was the 47th given up the Blyleven that season – giving him sole possession of the all-time record. Blyleven gave up three more home runs (two more in that September 29 game and one in an October 4 contest against the White Sox) to run the record to 50. Given how today’s pitchers are used that record also seems unbreakable.

Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of his 36 1986 starts. In the eight starts in which he did not surrender a long ball, he went 8-0.

Despite all the long balls and a 4.01 earned run average, Blyleven had a respectable season. He led the AL in innings pitched (271 2/3); his 17 wins (versus 14 losses) were the sixth most in the AL; he tossed 16 complete games (second in the AL); gave up the third-fewest walks per nine innings; and finished fourth in strikeouts with 215.

Of the record 50 home runs Blyleven allowed in 1986, 27 were solo shots.

Blyleven, by the way, went on to help the Twins to the World Series Championship in 1987 – going 15-12, 4.01 – and giving up 46 home runs. This gave the Twins’ righty the record for home runs allowed in consecutive seasons (96). What seems a bit surprising is that those two seasons were the only two – in Blyleven’s 22 MLB campaigns – that he gave up more than 24 home runs. He, in fact, had six seasons when he pitched more than 200 innings at gave up less than 20 round trippers. (In 1973, he pitched 325 frames and allowed just 16 home runs.) Blyleven’s career record was 287-250, 3.31 – with 3,701 strikeouts (currently fifth all-time) in 4, 970 innings pitched. He was a one-time 20-game winner, won 15 or more games in ten seasons amd threw 60 complet-game shutouts (ninth all-time).

Blyleven, by the way, went on to help the Twins to the World Series Championship in 1987 – going 15-12, 4.01 – and giving up 46 home runs. This gave the Twins’ righty the record for home runs allowed in consecutive seasons (96). What seems a bit surprising is that those two seasons were the only two – in Blyleven’s 22 MLB campaigns – that he gave up more than 24 home runs. He, in fact, had six seasons when he pitched more than 200 innings at gave up less than 20 round trippers. (In 1973, he pitched 325 frames and allowed just 16 home runs.) Blyleven’s career record was 287-250, 3.31 – with 3,701 strikeouts (currently fifth all-time) in 4, 970 innings pitched. He was a one-time 20-game winner, won 15 or more games in ten seasons amd threw 60 complet-game shutouts (ninth all-time).

Jay Bell got in just five MLB games in 1986, going five-for-sixteen (.357) with two doubles, the one home run and four RBI. He went on to play in 18 MLB seasons – and added 194 home runs to that record-tying and record-breaking first-pitch blast. He hit .265 over his career, with 860 RBI, 1,123 runs scored and 91 stolen bases. His best year was 1999 (Diamondbacks), when he hit .289, with 38 home runs 112 RBI and 132 runs scored.

More on Bert Blyleven’s 50-home run season:

- Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of this 36 starts.

- Blyleven gave up one home run in 15 games; two home runs in six contests; three round trippers in six contests; and five long balls in one game.

- Blyleven went 8-0 in starts when he did not give up a home run; 6-7 (two no-decisions) in starts in which he gave up one homer; 2-2 (two no-decisions) in starts in which he surrendered two long balls; 1-4 (one no-decision) in three-homer games; and 0-1 in games in which he gave up five home runs.

- He gave up a season high five home runs (in 5 ½ innings) in a start against Texas (in Minneapolis) on September 13. The long balls went to Pete O’Brien, Pete Incaviglia, Darrell Porter, Ruben Sierra and Steve Buechele. (Blyleven gave up nine runs in the game – eight on home runs.)

- Blylven gave up home runs to 38 different batters in 1986.

- The White Sox’ Ron Kittle hit the most home runs off Blyleven that season – four. The Brewers’ Ben Ogilvie had three and Blyleven gave up two homers each to Reggie Jackson (Angels), Don Mattingly (Yankees), Lance Parrish,(Tigers), Doug DeCinces (Angels) and Johnny Grubb (Tigers).

- The Tigers touched Blyleven for the most home home runs in 1986, with nine (four Blyleven starts against them). Next, at six home runs each were the: Rangers (rwo starts); Brewers (four starts); and White Sox (three starts).

- Blyleven got two wins – and gave up no home runs – in two starts against the Orioles.

Primary Resources. Baseball-Refrence.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT.

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member. Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

On this date (September 29), in 1986 Indians’ 2B Jay Bell and Twins’ pitcher Bert Blyleven crossed paths for the first time – and the encounter put both players into the MLB record books.

Bell was a 20-year-old rookie, playing his first MLB game and batting ninth. He was a September call up, after a .277-7=74 season at Double-A Waterbury of the Double A Eastern League.

Blyleven was in his 17th MLB season, had already won 228 major league games – and was on his way to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It clearly looked like advantage Blyleven.

Bell’s first trip to the plate came with two outs in the top of the third inning. (Blyleven had retired the first eight Cleveland batters in order, fanning three. On the future Hall of Famer’s first pitch to the rookie, Bell smacked a home run – tying an unbreakable MLB record (to date a total of 30 MLB players have homered on the first pitch they ever saw, Bell was just the twelfth to do so).

But the long ball had more significance. At the time of the at bat, Blyleven was tied with Hall of Famers Robin Roberts for the most home runs given up in a single season at 46. Bell’s round tripper broke that tie – and gave Blyleven the all-time record. Blyleven gave up three more home runs (two more in that September 29 games and one in an October 4 contest against the White Sox). Despite all the long ball and a 4.01 earned run average, Blyleven had a respectable season: he led the AL in innings pitched (271 2/3); his 17 wins (versus 14 losses) were the sixth most in the A; he tossed 16 complete games (second in the AL); gave up the third fewest walks per nine innings; and finished fourth in strikeouts with 215.

Of the record 50 home runs Blyleven allowed in 1986, 27 were solo shots.

Blyleven, by the way, went on to help the Twins to the World Series Championship in 1987 – going 15-12, 4.01 – and giving up 46 home runs. This gave the Twins’ righty the record for home runs allowed in consecutive seasons (96). What seem a bit surprising is that those two seasons were the only two – in Blyleven’s 22MLB campaigns – that he gave up more than 24 home runs. He, in fact, had six seasons when he pitched more than 200 innings at gave up less than 20 round tripped. (In 1973, he pitched 325 frames and allowed just 16 home runs. Blyleven’s career record was 287-250, 3.31 – with 3,701 strikeouts in 4, 970 innings pitched. He was a one-time 20-game winner, won 15 or more games in ten seasons.

Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of his 36 1986 starts. In the eight starts where he did not give up a long ball, he went 8-0.

Jay Bell got in just five MLB games in 1986, going five-for-sixteen (.357) with two doubles, the one home run and four RBI. He went on to play in 18 MLB seasons – and added 194 home runs to that record-tying and record-breaking first-pitch blast. He hit .265 over his career, with 860 RBI, 1,123 runs scored and 91 stolen bases. His bet year was 1999 (Diamondbacks0, when he hit .289, with 38 home runs112 RBT and 132 runs scored.

More on Bert Blyleven’s 50-home run season.

- Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of this 36 starts.

- Blyleven gave up one home run in 15 games; two home runs in six contests; three round trippers in six contests; and five long balls in one game.

- In the eight starts in which he did not give up a home run, Blyleven went 8-0.

- Blyleven was 6-7 (two no decisions) in starts in which he gave up one home; 2-2 (two no decision) in starts in which he surrender two long balls; 1-4 (one no decision in three-homer games; and 0-1 in five home run games.

- He gave up a season high five home runs (in 5 ½ innings) in a start against Texas (in Minneapolis) on September 13. The long balls went to Pete O’Brien, Pete Incaviglia, Darrell Porter, Ruben Sierra and Steve Buechele. (Blyleven gave up nine runs in the game – eight on home runs,

- The White Sox Ron Kittle hit the most home runs off Blyleven that season – four.

Primary Resource. Baseball-Refrence.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT.

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member. Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

On this date (September 29), in 1986 Indians’ 2B Jay Bell and Twins’ pitcher Bert Blyleven crossed paths for the first time – and the encounter put both players into the MLB record books.

Bell was a 20-year-old rookie, playing his first MLB game and batting ninth. He was a September call up, after a .277-7=74 season at Double-A Waterbury of the Double A Eastern League.

Blyleven was in his 17th MLB season, had already won 228 major league games – and was on his way to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It clearly looked like advantage Blyleven.

Bell’s first trip to the plate came with two outs in the top of the third inning. (Blyleven had retired the first eight Cleveland batters in order, fanning three. On the future Hall of Famer’s first pitch to the rookie, Bell smacked a home run – tying an unbreakable MLB record (to date a total of 30 MLB players have homered on the first pitch they ever saw, Bell was just the twelfth to do so).

But the long ball had more significance. At the time of the at bat, Blyleven was tied with Hall of Famers Robin Roberts for the most home runs given up in a single season at 46. Bell’s round tripper broke that tie – and gave Blyleven the all-time record. Blyleven gave up three more home runs (two more in that September 29 games and one in an October 4 contest against the White Sox). Despite all the long ball and a 4.01 earned run average, Blyleven had a respectable season: he led the AL in innings pitched (271 2/3); his 17 wins (versus 14 losses) were the sixth most in the A; he tossed 16 complete games (second in the AL); gave up the third fewest walks per nine innings; and finished fourth in strikeouts with 215.

Of the record 50 home runs Blyleven allowed in 1986, 27 were solo shots.

Blyleven, by the way, went on to help the Twins to the World Series Championship in 1987 – going 15-12, 4.01 – and giving up 46 home runs. This gave the Twins’ righty the record for home runs allowed in consecutive seasons (96). What seem a bit surprising is that those two seasons were the only two – in Blyleven’s 22MLB campaigns – that he gave up more than 24 home runs. He, in fact, had six seasons when he pitched more than 200 innings at gave up less than 20 round tripped. (In 1973, he pitched 325 frames and allowed just 16 home runs. Blyleven’s career record was 287-250, 3.31 – with 3,701 strikeouts in 4, 970 innings pitched. He was a one-time 20-game winner, won 15 or more games in ten seasons.

Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of his 36 1986 starts. In the eight starts where he did not give up a long ball, he went 8-0.

Jay Bell got in just five MLB games in 1986, going five-for-sixteen (.357) with two doubles, the one home run and four RBI. He went on to play in 18 MLB seasons – and added 194 home runs to that record-tying and record-breaking first-pitch blast. He hit .265 over his career, with 860 RBI, 1,123 runs scored and 91 stolen bases. His bet year was 1999 (Diamondbacks0, when he hit .289, with 38 home runs112 RBT and 132 runs scored.

More on Bert Blyleven’s 50-home run season.

- Blyleven gave up at least one home run in 28 of this 36 starts.

- Blyleven gave up one home run in 15 games; two home runs in six contests; three round trippers in six contests; and five long balls in one game.

- In the eight starts in which he did not give up a home run, Blyleven went 8-0.

- Blyleven was 6-7 (two no decisions) in starts in which he gave up one home; 2-2 (two no decision) in starts in which he surrender two long balls; 1-4 (one no decision in three-homer games; and 0-1 in five home run games.

- He gave up a season high five home runs (in 5 ½ innings) in a start against Texas (in Minneapolis) on September 13. The long balls went to Pete O’Brien, Pete Incaviglia, Darrell Porter, Ruben Sierra and Steve Buechele. (Blyleven gave up nine runs in the game – eight on home runs,

- The White Sox Ron Kittle hit the most home runs off Blyleven that season – four.

Primary Resource. Baseball-Refrence.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT.

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member. Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Scherzer Rolls a 300 – Joins an Elite Pitching Fraternity

Photo by Keith Allison

Tonight (September 25, 2018), three-time Cy Young Award winner Max Scherzer became the 40th pitcher in major league history – and just the 17th since 1900 – to reach 300 strikeouts in a season. Scherzer ran his 2018 total to 300 by fanning ten Marlins in seven innings (five hits, one earned run and no walks) as the Nationals won 9-4. On the season, Scherzer is now 18-7, 2.53 with 300 strikeouts in 220 2/3 innings pitched. Scherzer fanned one batter each in the first, third, fifth and sixth innings and two each in the second, fourth and seventh. His tenth victim of the game and 300th of the season was Marlins’ LF Austin Dean for the second out in the seventh.

Here, in honor of Scherzer’s feat, are a few 300-strikeout tidbits.

- 41 MLB pitchers have turned in 67 seasons of 300 or more strikeouts – 31 of those before 1900.

- 1884 saw a record 15 pitchers notch at least 300 strikeouts – since then, there have never been more than five in any single season (1886). Since 1900, there has never been more than two 300 strikeout pitchers in any season.

- Currently active pitches with 300-strikeout seasons, in addition to Scherzer, are: Chris Sale (308 in 2017) and Clayton Kershaw (301 in 2015).

The Exclusive 500 Club

Only one MLB pitcher has ever fanned 500 batters in a season – and that was Matt Kilroy, who whiffed 513 batters in 583 innings as a 20-year-old rookie with the 1884 American Association Baltimore Orioles. Of course, it was a different game back then.

In 1884, Kilroy started 68 of the Orioles 139 games (49 percent) – and completed 66 of them. (That season, American Association starting pitchers finished an average of 96 percent of their starts.) Despite five shutouts and a 3.37 earned run average (the league ERA was 3.44), Kilroy finished 29-34 for the last-place (46-85) Orioles.

While Matt Kilroy is the only major league pitcher to ever reach 500 strikeouts in a season, five more have reached 400.

- There were no 300-strikeout campaigns between 1912 (Walter Johnson – 303) and 1946 (Bob Feller – 348).

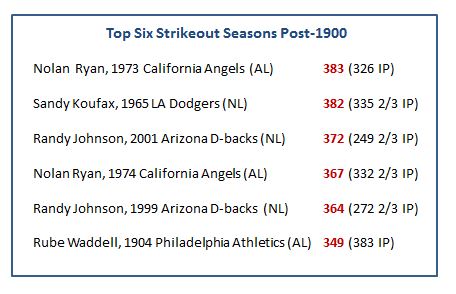

- Rube Waddell’s 349 strikeouts in 1904 stood as the post-1900 record for 61 years (Sandy Koufax – 382 in 1965). Koufax’ record held for just eight seasons (Nolan Ryan – 383 in 1973, still the post-1900 MLB record). Koufax still holds the NL post-1900 record for whiffs in a season.

- The only team to boast two 300+ strikeout pitchers in the same season is the 2002 Diamondbacks – Randy Johnson (334) and Curt Schilling (316).

- The decade of the ‘70s (1970-79) saw 11 seasons of 300 or more whiffs by a pitcher – the most in any decade post-1900.

- From 1900 through 1962, there were a total of just five 300 or more strikeout campaigns.

Primary Resources: Baseball-Reference.com; MLB.com.

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Trivia Teaser – Last Season in which Both ERA Leaders were Under 2.00

The current MLB earned run average leaders are the Mets’ Jacob deGrom in the National League at 1.77 and the Rays’ Blake Snell in the American League at 1.90.

TRIVIA TEASER

When was the last season MLB saw the earned run leaders in both the National and American League at under 2.00?

That would be 1972 with the Red Sox’ Luis Tiant (1.91) and Phillies’ Steve Carlton (1.97).

Just to illustrate how much the game has changed, there have been a total of 249 instances in which a qualifying hurler (one inning pitched for each game his team played) has recorded a season earned run average of under 2.00 – and 204 of those occurred before 1920. Here’s look at the number of qualifying earned run averages under-2.00 in each time period.

Pre-1900 … 46

1900-1919 … 158

1920-29 … 2

1930-39 … 1

1940-49 … 5

1950 – 59 … 1

1960-69 … 14

1970-79 … 8

1980-89 … 3

1990-99 … 5

2000-2009 … 2

2010 – 2017 …. 4

The leader in total qualifying seasons with an earned run average under 2.00 is the Senators’ Walter Johnson with ten over a 21-season career (1907-1927). His qualifying under 2.00 seasons were: 1908 – 1.65; 1910 – 1.36; 1911 – 1.90; 1912 – 1.39; 1913 – 1.14; 1914 – 1.72; 1915 – 1.55; 1916 – 1.90; 1918 – 1.27; 1919 – 1.49. Johnson finished his career with 417 wins (279 losses) and a 2.17 earned run average.

The leader in total qualifying seasons with an earned run average under 2.00 is the Senators’ Walter Johnson with ten over a 21-season career (1907-1927). His qualifying under 2.00 seasons were: 1908 – 1.65; 1910 – 1.36; 1911 – 1.90; 1912 – 1.39; 1913 – 1.14; 1914 – 1.72; 1915 – 1.55; 1916 – 1.90; 1918 – 1.27; 1919 – 1.49. Johnson finished his career with 417 wins (279 losses) and a 2.17 earned run average.

The post-1919 leader in seasons with a qualifying ERA under 2.00 is the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax with three: 1963 – 1.88; 1964 – 1.74; 1966 – 1.73. Koufax retired at 165-87, 2.76 (over 12 seasons … 1955-66).

Tim Keefe of the National League 1880 Troy Trojans – a team that went 41-42 – recorded the major league’s lowest-ever qualifying ERA at 0.86 – giving up just ten earned runs in 12 starts (all complete games, 105 innings pitched). Despite the league’s stingiest ERA, Keefe went 6-6 on the season. (The league ERA that season was 2.37 – and three of the eight teams has ERAs under 2.00.) Keefe pitched 14 MLB seasons (1880-93), going 342-225, 2.63.

The lowest post-1899 ERA goes to the Red Sox’ Dutch Leonard at 0.96 in 1914, when he went 19-5, 0.96, while pitching 224 innings. Leonard was 139-114, 2.76 for his 11-season MLB career (1913-21; 1924-25). Side note: The lowest post-1919 qualifying ERA … and fourth-lowest all time … belongs to Bob Gibson, who went 22-9, 1.12 in 1968. The next lowest post-1919 season ERA was Dwight Gooden’s 1.53 for the Mets in 1985 – when the 20-year-old went 24-4.

Primary Resource: Baseball-Reference.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliqaury. The Negrpo Leagues Baseball Museum.

A Look at The Past (and not so bright future) of Complete-Game Shutouts

On this date (September 22) in 1911, right-hander Cy Young won his 511th and final major league regular-season game. It was, fittingly, a complete-game shutout – a 1-0 Boston Rustlers win over the Pittsburgh Pirates. It brought Young’s career record to 511-313, and he should have quit while he was ahead. The 44-year-old Young, in his 22nd MLB season, was 7-6 on the on the 1911 season at the time. Young pitched just three more games that season – going 0-3 and giving up 21 runs in 22 2/3 innings.

That final win – again, a complete-game shutout – led Baseball Roundtable to look at the past (and likely dismal future) of complete-game white-washings. As Idid that, I learned that Young was one of just 26 pitchers in MLB history to notch double-digit shutouts in a season.

Trivia Teaser – Who was the last pitcher to log double-digit complete-game shutouts in a season?

That would be southpaw John Tudor of the Cardinals – back in 1985. That season, Tudor went 21-8, with a 1.93 earned run average for the Redbirds. He tossed 14 complete games in 36 starts, and ten of those complete-game outings were shutouts. It was the only season Tudor’s 12-campaign MLB career in which he threw more than two shutouts. (He had a career total of 16 CG shutouts.) Tudor finished his career at 117-72, 3.12, with 50 complete games in 263 starts.

The last American Leaguer to throw at least ten shutouts in a season was Orioles’ right-hander (and Hall of Famer) Jim Palmer in 1975. That season, Palmer went 23-11, 2.09 and tossed 25 complete games in 38 starts. Palmer’s career line was 268-152, 2.86 with 211 complete games and 53 shutouts in 521 starts.

There have been 28 instances of pitchers logging ten or more shutouts in a season – and 26 pitchers have accomplished the feat. Only two have logged ten or more shutouts in a season more than once: The Phillies’ Grover Cleveland (Pete) Alexander (12 shutouts in 1915 and an MLB-record 16 shutouts in 1916) and the White Sox’ Ed Walsh (10 shutouts in 1906 and 11 whitewashings in 1908).

How Likely Are We to See Ten Shutouts in a Season in Today’s Game?

Since the 2000 season, only one pitcher has thrown at least ten complete games in a season (James Shields of the Rays with 11 in 2011) – much less ten shutouts.

In 2017, the most shutouts by any pitcher was three (Corey Kluber, Indians and Ervin Santana, Twins) and the most complete games was five (same two pitchers). As this post is written no pitcher has more than two complete games or more than one CG shutout in the 2018 season.

A few more shutout tidbits.

- Walter Johnson (Senators … 1907-1927) holds the career shutout record with 110. No one else has more than 90.

- The record for shutouts in a season is 16 shared by Grover Cleveland (Pete) Alexander (Phillies, 1916) and George Bradley (Saint Louis Brown Stockings, 1876).

Babe Ruth shares the AL record for shutouts in a season by a southpaw at nine (Red Sox, 1916). Yankee Ron Guidry also threw nine shutouts (1978).

- Walter Johnson, who drew the Opening Day assignment in 14 seasons, threw a record seven Opening Day shutouts.

- On August 10, 1944 The Braves’ Red Barrett shutout the Red 2-0 – throwing only 58 pitches (the fewest pitches ever – not just in a shutout, but in a nine-inning complete game of any score.) Barrett pitched a two-hitter with zero walks and zero strikeouts.

- Don Drysdale of the Dodgers tossed a record six consecutive complete-game shutouts between May 14, 1856 and June 4, 1968.

Playing the Lead Role

In 2008, C.C. Sabathia led the AL, NL and MLB in shutouts. He started the season with the Cleveland Indians and was 6-8, 3.83 with three complete games and two shutouts before being traded to the NL Milwaukee Brewers on July 7. With the Brewers, Sabathia went 11-2 with seven complete games and three shutouts. His two AL shutouts tied for the American League lead, while he three whitewashings tied for the NL lead.

______________________________________________________________

Pitchers with Ten or More Shutouts in a Season

George Bradley, 1876 St. Louis Brown Stockings (NL) ….. 16

Pud Galvin, 1884, Buffalo Bisons (NL) ….. 12

Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, 1884 Providence Grays (NL) ….. 11

Jim McCormick, 1884 (two teams) ….. 10

John Clarkson, 1885 Chicago White Stockings (NL) ….. 10

Ed Morris, 1886 Pittsburgh Alleghenys (AA) ….. 12

Dave Foutz, 1886 Saint Louis Browns (AA) ….. 11

Tommy Bond, 1879 Boston Red Stockings (NL) ….. 11

Christy Mathewson, 1908 Giants (NL) ….. 11

Cy Young, 1904 Boston Americans (AL) ….. 10

Ed Walsh, 1906 White Sox (AL) ….. 10

Ed Walsh, 1908 White Sox (AL) ….. 11

Jack Combs, 1910 Athletics (AL) ….. 13

Smokey Joe Wood, 1912 Red Sox (AL) ….. 10

Walter Johnson, 1913 Senators (AL) ….. 11

Grover Cleveland Alexander, 1915 Phillies (NL) ….. 12

Grover Cleveland Alexander, 1916 Phillies (NL) ….. 16

Dave Davenport, 1915 St. Louis Terriers (FL) …..10

Carl Hubbell, 1933 Giants (NL) ….. 10

Mort Cooper, 1942 Cardinals (NL) ….. 10

Bob Feller, 1946 Indians (AL) ….. 10

Bob Lemon, 1948 Indians (AL) ….. 10

Sandy Koufax, 1963 Dodgers (NL) ….. 11

Dean Chance, 1964 Angels (AL) ….. 11

Juan Marichal, 1965 Giants (NL) ….. 10

Bob Gibson, 1968 Cardinals (NL) ….. 13

Jim Palmer, 1975 Orioles (AL) ….. 10

John Tudor, 1985 Cardinals (NL) … 10

Primary Resouces: MLB.com; Baseball-reference.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

I tweet baseball @David BBRT

Like/Follow the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Indians on the Verge of History – Soon to Boast Four 200K Hurlers

Photo by apardavila

Tonight (September 18), Indians’ starter Corey Kluber fanned 11 batters in eight innings, as Cleveland topped the White Sox 5-3 in Cleveland. Kluber’s performance enabled the Indians to tie a MLB record – and put them on the cusp of breaking that record.

Kluber ran his season strikeout total to 205 (in 203 innings) – joining two other Cleveland starters with 200+ strikeouts this season – Carlos Carrasco (206 strikeouts/176 innings) and Trevor Bauer (214 strikeouts/166 innings). This makes the Indians just the fourth team in MLB history with three pitchers notching 200 or more whiffs in the same season.

The others are:

- 1967 Minnesota Twins: Dean Chance (220 Ks), Jim Kaat (211), Dave Boswell (204);

- 1969 Astros: Don Wilson (235), Larry Dierker (222), Tom Griffin (200);

- 2013 Tigers: Max Scherzer (240), Justin Verlander (217), Anibel Sanchez (202).

Now, perhaps, the even bigger news. A fourth Indians’ starter – Mike Clevinger – currently stands at 196 strikeouts in 188 1/3 innings – which means MLB will likely soon see the first team ever with four pitchers notching 200 or more strikeouts in the same season.

Special thanks to Baseball Roundtable reader Benjamin Thobe for alerting BBRT to the Indians’ march toward the new record.

Side note: The Houston Astros should end the season with three 200+ strikeout pitchers. Currently, Justin Verlander stands at 269 strikeouts, Gerrit Cole at 260 and Charlie Morton at 195.

For an earlier post with more detail on the first three teams to have three 200K starters in the same season, click here.

I tweet Baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Christian Yelich Red(s) Hot … Records His Second Cycle of the Season

Photo by DandreaPhotography

Yesterday (September 17, 2018), Brewers’ left fielder Christian Yelich hit for the cycle (single, double, triple, home run in the same game), as the brew crew topped the Reds’ 8-0 in Milwaukee. It was his second cycle of the 2018 season – and both came against the Reds. (The first cycle was on August 29 at the Great American Ball Park.) In yesterday’s contest, Yelich went four-for-four, with one run scored and four RBI.) He singled in the first inning, doubled in the third, hit a home run (with one on) in the fifth and got the most-often elusive triple in the sixth.

Two cycles in a season is a rare accomplishment indeed. In fact, Yelich is only the fifth major leaguer to accomplish that feat. The others are:

- Aaron Hill (Diamondbacks, 2012);

- Babe Herman (Dodgers 1931);

- Tip O’Neill (St. Louis Browns, American Association 1887): and

- John Reilly (Cincinnati Red Stockings, American Association, 1883).

Here are a few other cycle tidbits that yo may find of interest.

The Yellow Jersey of Cycles

On June 18, 2000, the Rockies’ Mike Lansing completed the cycle in just four innings – making his the quickest cycle in MLB history – and earning him the “yellow jersey” of baseball cyclists. Notably, Lansing was consistently behind in the counts and three of his four hits came with two strikes.

Lansing, hitting second in the order, hit an RBI triple to right in the first inning (getting the most difficult leg of the cycle out of the way ) on a 1-2 pitch, added a two-run home run (0-1 pitch) in the bottom of the second, hit a two-run double (2-2 pitch) in the bottom of the third (as the Rockies scored nine times to take a 14-1 lead), and then completed the cycle with a single (another 1-2 offering) to right in the fourth. Lansing then struck out in the sixth, before being lifted for a pinch-hitter in the eighth.

Quickest Cycle Ever … A Career Perspective

Minnesota Twins’ outfielder Gary Ward hit for the cycle in just his 14th MLB game (September 18, 1980 against the Brewers) – the earliest in an MLB career anyone has ever accomplished the feat.

Triple Your Pleasure – Triple Your Fun

Four players have hit for the cycle a record three times: Adrian Beltre (Mariners-2008, Rangers-2012 and 2015); Bob Meusel (Yankees-1921, 1922 and 1928); Babe Herman (Brooklyn Robins-1931 twice and Cubs-1933); John Reilly (Red Stockings-1883 twice and Reds 1890).

Gotta Love the Texas – and More of “We Track Pretty Much Everything in Baseball”

Adrian Beltre’s record-tying three cycles – although hit for two different teams – all took place at the Texas Rangers’ home park (Globe Life Park in Arlington). He cycled there twice for the hometown Rangers and once for the visiting Mariners, making him the only player to hit for the cycle in the same stadium for two different teams.

Shortest Time Between Cycles

John Reilly (Reds) and Tip O‘Neill (St. Louis Brown Stockings, American Association) had the shortest time between cycles at just seven days. Reilly’s came on September 12 and September 19, 1883. O’Neill’s came on April 30 and May 7, 1887.

It’s Been a Hard Day’s Night

The Expos’ Tim Foli is the only player to start a cycle one day and complete it the next. On April 21, 1976, Foli collected a single, double and triple in a contest against the Cubbies that was suspended (pre-Wrigley lights) in the top of the seventh due to darkness. When play resumed the following day, Foli added an eighth-inning home run. (The Expos prevailed 12-6.)

Patience is a Virtue

The longest time between cycles for a player with multiple cycles goes to the Royals’ George Brett (May 28, 1979 and July 25, 1990) at 11-years-58 days.

Something Old … Someting New

The youngest MLB player ever to hit for the cycle is the NY Giants’ Mel Ott (age 20, cycle on May 16, 1929).

The oldest player to hit for the cycle is The Angels’ Dave Winfield (age 39, cycle on June 24, 1991).

Like Father … Like Son

When Twins outfielder Gary Ward hit for the cycle in just his 14th MLB game (September 18, 1980), he not only recorded the earliest (in terms of MLB games played) cycle ever, he also set the stage for an event that would add to the “rare and unique” nature of his cycle nearly a quarter-century later. On May 26, 2004, Ward’s son Daryle Ward – playing 1B and batting third for the Pirates as they took on the Cardinals in St. Louis – also hit for the cycle. Gary and Daryle Ward are the only father-son combination (to date) to hit for the cycle.

Sharing the Wealth

Three players have hit for the cycle in both the NL and AL: Bob Watson (NL Astros-1977 and AL Red Sox-1979); John Olerud (NL Mets-1997 and AL Mariners-2001); Michael Cuddyer (AL Twins-2009 and NL Rockies-2014).

Qoute the Raven, “Nevermore”

The Marlins are the only MLB team to never have a batter record a cycle.

A Most Unique Way to Record A Cycle

The Yankees’ 1B Lou Gehrig (kind of) earned a cycle by being tossed out at the plate. On June 25, 1934, as New York topped Chicago 13-2 at Yankee Stadium, Gehrig hit two-run home run in the first inning; a single in the third; and a double in the sixth. Gehrig came up needing just the triple for the cycle in the seventh and hit a smash to deep center (scoring Yankees’ CF Ben Chapman). Gehrig wasn’t satisfied with a three-bagger and was thrown out at home (8-6-2) trying for an inside-the-park home run – thus getting credit for the triple he needed for a cycle.

It Skips A Generation

Pirates’ RF Gus Bell and Phillies’ 3B David Bell are the only grandfather-grandson combination to hit for the cycle (June 4, 1951 and June 28, 2004, respectively).

The Home Run Cycle

Only once in professional baseball has a player hit for the “Home Run Cycle” – solo, two-run, three-run and GrandSlam homers in the same game. Read that story here.

Primary Resources: Society for American Baseball Research; Baseball-Reference.com; MLB.com; Baseball-Almanac.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like Baseball Roundtyable’s Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

George Sisler … Babe Ruth Lite?

This is a tale of two left-handed pitchers named George who also both proved they could handle the bat pretty well.

On this date (September 17 in 1916) a 23-year-old southpaw pitcher – in just his second MLB season – took the mound for the Saint Louis Browns against future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson (Washington Senators). On the surface, it seemed a mismatch.

Johnson was in his tenth major league season – with a career record of 231-145, and a 1.64 career earned run average. He had already led the AL in strikeouts five times (including the four previous seasons) and in victories the three previous seasons. At that point in the 1916 season, he was 25-17, with a 1.84 earned run average – on his way the leading the AL in wins, complete games, innings pitched and strikeouts.

Johnson’s mound opponent had gone 4-4. 2.83 as a rookie in 1915 (with 15 mound appearances and six complete games in eight starts. He came into the game against Johnson with 0-1 record on the year – his one pitching appearance being a 1-0 complete-game loss.

Further, Johnson had solid motivation to top his opponent. The previous season, in a matchup against the same left-hander, Johnson had been bested 2-1 in a pitching duel that saw both hurlers go the distance. Johnson gave up two runs on six hits, the rookie allowed one run on six safeties.

On that September 2016 afternoon, Johnson again was outpitched – despite giving up just one run (unearned) on four hits, while walking two and fanning eight. His opponent, like Johnson, went the distance – pitching a six-hit, two-walk, six-strikeout, shutout. It would, ironically, be his last pitching victory. (Johnson, however, would go on to 166 more wins.) It would not, however, be his last major league game. In fact, the Browns’ starting pitcher would go on to play 13 more seasons, earning his own spot in the Hall of Fame – with his bat and glove, rather than his pitching arm.

Who was that southpaw who won both his matchups against Walter Johnson – giving up just one run in 18 innings? Future Hall of Famer George Sisler, who – like another hitter who came up as a pitcher (Babe Ruth) – would prove master batsman. Playing primarily at first base (where he earned a reputation as an excellent fielder), Sisler collected 2,812 MLB hits, put up a career .340 average, won two batting titles (hitting .407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922), led the AL in stolen bases four times, triples twice, base hits twice (his 257 hits in 1920 would stand as the MLB record until 2004) and runs scored once. Sisler hit over .300 in 13 of his 15 MLB seasons, topping .350 five times. He stole a total of 375 bases, with a high of 51 in 1922. He also had 100+ RBI in four campaigns, 100 or more runs in four seasons and 200+ hits in six seasons.

Overshadowed by the Babe

In 1920, when George Sisler set a then MLB record with 257 hits (and led the AL with a .407 average), he also set a career high with 19 home runes. He was overshadowed by another former left-handed pitcher named George (George Herman “Babe” Ruth) who hit “only” .376, but shattered the MLB home run record with an unheard of 54 round trippers (breaking his own record of 29).

That season, Sisler finished second to Ruth in home runs (54-19); runs (158-137) and RBI (135-122), but did top the Babe in total bases (399-388).

Like Ruth, Sisler would occasionally take a turn on the mound later in his career (twice in 1918 and once each season in 1920, 1925, 1926 and 1928). His career pitching line in 24 games (12 starts) was 5-6, 2.35, with nine complete games and one shutout.

The Sisler – Rickey Connection

Branch Rickey and George Sisler are both in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but their connections run much deeper.

- Sisler’s college coach (at the University of Michigan) was Branch Rickey.

- Sisler’s first MLB manager (with the 1915 Saint Louis Browns) was Branch Rickey.

- In World War I, Sisler served in a chemical warfare training unit commanded by Branch Rickey.

- From 1942 through 1950, Sisler worked as a scout (he reportedly scouted Jackie Robinson) and player development coach for the Dodgers (under Branch Rickey).

- In 1952, when Branch Rickey joined the Pirates’ organization, he hired Sisler as a roving coach.

![[George Sisler, University of Michigan (baseball)] (LOC) by The Library of Congress George Sisler photo](https://baseballroundtable.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/3295497074_1b35a93f45_m_George-Sisler.jpg)

Photo by The Library of Congress

Cassius Clay Connection

George Sisler was the son of Mary Whipple and Cassius Clay Sisler.

When he joined the Saint Louis Browns in 1915, Sisler’s manager Branch Rickey – who had witnessed his college pitching and batting prowess (Sisler hit over .400 in his college baseball career) – began working him out at first base and in the outfield. The results, as noted earlier, were spectacular.

Baseball Genes

Two of George Sisler’s three sons made it to the major leagues as players, while the third served as a minor league executive.

- Dick Sisler hit .276 in eight seasons (799 games – Cardinals, Phillies, Reds) as an MLB outfielder/first baseman and went on to manage the Cincinnati Reds (1964-65) and later serve as a coach with the Cardinals, Padres, and Mets.

- Dave Sisler pitched in seven MLB seasons (Red Sox, Tigers, Senators, Reds) going 38-44, 4.33 with 28 saves (247 games, 59 starts).

- George Sisler, Jr. was a general manager for several minor league teams and served as the President of the International League for a decade (1966-76).

Primary resources: Society for American Baseball Research; The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball Forgotten Giant (Rick Huhn, University of Missouri, 2004); Baseball Hall of Fame; Baseball-Reference.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Like/Follow the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro League’s Baseball Museum.

Fun with Faust – The Short and Improbable MLB Career of Charles “Victory” Faust

How does a pitcher of, at best, minimal skills, who made his professional debut at age 30, appeared in only two games (two innings) and never recorded an MLB win earn the nickname “Victory?”

Well, it helps if your middle name is “Victor.” It also helps if you believe in fortune tellers, are slightly “off balance” and can find a manager and team that can be convinced you are a good luck charm that can bring them a successful trip to the World Series. All those forces came together to create a “perfect storm” in the short, zany and improbable life and major league “career” of Charles ”Victory” Faust.

Side note: BBRT has often talked about how, when looking into baseball “tidbits,” one thing can often lead to another – and another – and another. In this case, research BBRT was putting together a post on a unique connection between two players who were hit by a pitch (in their first – and for one only – plate appearance) fifty years apart led BBRT to a look at a third player who also was clipped by a pitch in his first (and only) MLB plate appearance. For a look at the post that led to this article, click here. Anyway, that’s the roundabout way I got to this post about Charles “Victory” Faust.

As I prepared this post, it became clear that record-keeping (and even “eye-witnessing”) were not exact sciences among ballplayers in the early 1900s. I worked to distinguish between myth and reality as I looked into the life of Charles Faust, but can’t guarantee a bit of myth may have slipped by. Still, even when you discount likely myth, there is plenty of magic in this Faust-ian tale.

Charles Victor Faust – an awkward and somewhat slow fellow in many ways – grew up on a Kansas farm and did not appear to have an overly bright future. That is, not until the spring of 1911, when he availed himself of a country fair fortune teller – who told him (among other things) that he was destined to marry a California woman named Lulu and pitch the New York Giants to a World Series championship. The 30-year-old Faust – apparently with child-like enthusiasm, intellect and trust – took the predictions to heart. Despite his total inexperience as a pitcher, Faust’s focus in life became finding a way to convince Giants’ Manager John McGraw to enable him to pursue his destiny.

In late July, Faust traveled to Saint Louis, where the Giants were facing the Cardinals. Now, there are a couple of versions of what took place in Saint Louis. One says that Faust approached McGraw at the team’s hotel and related the fortune teller’s prediction, promising that he would fulfill his destiny and pitch the Giants to the World Championship. The other is that Faust bought a ticket to the Giants/Cardinals game and, during pre-game warm-ups, simply stepped out onto the field and approached McGraw.

In either case, Faust – who may have seemed a bit odd to McGraw, but was certainly sincere enough – got his tryout with during that day’s pre-game warmups. (The tendency of baseball players and managers of the time toward superstition may have swayed McGraw to want to explore the efficacy of the fortune-teller first-hand; or Faust’s tryout may have been just a whim intended to break up the day’s routine.)

How talented was Faust? Well, after a few pitches from Faust (who was still in his street clothes), McGraw ditched his glove and caught his offerings barehanded (most likely to embarrass and discourage the eager, but inadequate, hurler).

“His windup was like a windmill. Both arms went around in circles for quite a while before Charlie finally let go of the ball. Well, regardless of the sign that McGraw would give, the ball would come up just the same. There was no difference in his pitches whatsoever. And there was no speed – probably enough to break a plane of glass, but that was about all.”

NY Giants’ CF Fred Snodgrass, describing Charlie Faust’s tryout deliveries in Lawrence S. Ritters’s book “The Glory of Their Times – The Story of the Early Days of Baseball told by the Men Who Played it.”

When McGraw’s bare-handed catching didn’t diminish Faust’s confidence, the manager tried another tack. He told Faust to take a few batting practice swings. Faust swung and missed a few lollipop offerings, before finally making weak contact. With that contact, McGraw urged Faust to run around the bases – sliding into each one, tattering his Sunday-best clothes, picking up a few scrapes, but (apparently) not bruising his ego or dampening his conviction.

Well, as one might expect, McGraw send the Faust on his way without a contract. The Giants, however, won big that day and when the still undaunted Faust showed up at the park the next day, the players reportedly put him in a spare uniform and sent him on out for another pre-game exhibition of his “skills” (most likely for their own amusement). The ensuing laughter did not embarrass the affable Faust. Rather he liked the attention and felt he had made a step forward in his quest. That day, with Faust as the pre-game show, the Giants again topped the Cardinals and the following day, they enjoyed a repeat performance from Faust and another victory. A pattern was developing.

The next day, as the team left Saint Louis, the fun (at least for McGraw) was over and the team unceremoniously ditched the gullible Faust at the railroad station. Two similar stories are reported here, both have the team sending him back to the team’s hotel on a fool’s errand – to retrieve either his contract or his train ticket. (Neither, of course, existed. The Giants, without Faust as a good luck charm, lost four of the next six games and were again seeming more like a third- or fourth-place squad than a pennant contender.

When the team returned home to New York, who should be waiting for them but Faust, as enthusiastic as ever about his role as the key to the Giants’ championship. The ballplayers – and McGraw – again, being a generally superstitious bunch, were receptive to Faust rejoining the squad. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Faust stayed with the team and became a popular source of pregame entertainment for fans. He would warm up, take batting practice, shag flies and run the bases – at which times his awkward, but energetic, displays would delight the fans (and sports reporters). Even opposing players would get into the act, sometime hitting against Faust in their own batting practices and “striking out” against his soft tosses. There was some less than good natured laughter, but Faust did not seem to notice; relishing his spot on the squad and warming up in the bullpen nearly every game – so he would be ready when he was needed on the mound. (The story goes that when the Giants would fall behind, McGraw would have Faust warmup in the bullpen – and, inevitably, the Giants would rally.) Faust was fast-becoming the toast of the town.

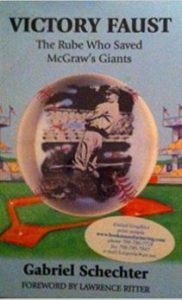

Faust, indeed, also proved a good luck charm for the New York squad – some speculated just by keeping the team happy and “loose.” One thing is clear, his conviction that he and the Giants were headed for greatness was unshakeable – and perhaps contagious. As Gabriel Schechter author of the book “Victory Faust – The Rube Who Save McGraw’s Giants” reports, as the season went on, the team went 36-2 when Faust was with them and just 3-7 when he wasn’t. (A bit of explanation on at least some those absences: Faust became so popular in New York that he was offered a job on vaudeville, telling stories, duplicating his windup and imitating the stars of the game. In his first three days in show business, the Giants went without a win, and Faust returned to his team and what he saw as his true destiny.)

Still Faust was not satisfied and kept badgering McGraw to give him a chance to toe the rubber in a game.

On October 5, the Giants clinched the pennant, but they still had a week’s worth of meaningless games until the fortune teller-predicted and Faust-promised World Series. And, Faust was still driven to appear on the mound. He had not – as predicted – “pitched” the Giants to success. He was about to get his wish.

On October 7, McGraw relented to Faust’s consistent badgering and brought him in to pitch the ninth inning of a game in which the Giants trailed the Boston Rustlers (Braves) 4-2. Faust, throwing fat pitches out of his exaggerated windmill-style windup actually managed to get out of the inning giving up just one run on one-hit (a double) and a sacrifice fly.

In the bottom of the ninth, the Giants made the final out with Faust on deck. But Faust, still showing his unbridled (perhaps slightly off-kilter) enthusiasm took his place in the batters’ box and refused to leave the field. And then a strange thing happened. The Boston players “played” along, stayed on the field and pitched to Faust. When he tapped a ball to the infield, the Boston players mishandled each throw and tag attempt until finally retiring a clumsily sliding (but surely smiling) Faust about ten feet from home plate. Although the at bat didn’t count, Faust had made his (and the fortune-teller’s) dream come true – he had pitched in a major league game. But he wasn’t done yet.

On October 12, in the final inning of the Giants’ final regular season game, with New York trailing the Brooklyn Superbas (Dodgers) 5-1, Faust pitched again – notching a scoreless frame. This time, he came to the plate when it counted And, like their Boston counterparts, the Brooklyn squad played along. Apparently believing there was little chance the awkward Faust could be counted on to hit the ball, Brooklyn pitcher Eddie Dent “dented” Faust with a pitch. Faust then, being largely ignored (or, perhaps, even encouraged) by the Brooklyn team, stole second and third base before scoring on a groundout. Quite an end to the season, and the World Series was ahead. It was also quite the end to Faust’s major league career.

Despite Faust’s presence, the Giants lost the World Series to the Philadelphia Athletics four games to two – and McGraw seemed to lose interest in the New York’s good luck charm.

The Giants did not invite Faust back in 1912 – but, no surprise, he showed up anyway. And, in a tribute to persistence, was again allowed to provide pre-game hijinks at the Polo Grounds (the team declined to pay his travel expenses for away games that season). Although the Giants (who would have expected otherwise) got off to a 54-11 start, McGraw had tired of Faust’s continued badgering about the opportunity to take the mound – and Faust was convinced to leave the team in mid-season.

The Giants won more than 80 percent of the games they played while Faust was with the team.

Faust moved back to Kansas, then California (perhaps, looking for Lulu) and eventually to Seattle (near one of his brothers) still insisting he would make it back to help the Giants win another pennant. It was not meant to be. In December of 1914, Faust was committed to an Oregon mental hospital, where he was diagnosed with dementia and (after several weeks of treatment) released in his brother’s care. Faust died June 18, 1915 (at age 34) of tuberculosis. Often described a “delusional,” the fact is Charles “Victory” Faust made it to the big leagues and did earn a pair of turns on the mound for a pennant winning club. In doing so, he carved a spot for himself as one of the more memorable characters in baseball history – and realized a dream that lives in most baseball fans’ hearts.

In 1915, the year Charles “Victory” Faust passed away, the New York Giants finished last in the National League – their first last-place finish since 1900. It would, in fact, be their only last place finish between 1900 and 1943.

Charles “Victory’ Faust – MLB Record

Pitching:

Games … 2. W-L … 0-0. Innings pitched … 2. Hits … 2. Earned runs … 1. ERA … 4.50.

Hitting

Plate appearances … 1. At Bats … 0. Hits … 0. Walks … o. Hit By Pitch … 1. Stolen bases … 2. Runs scored … 1. RBI … 0.

A final note: You can probably file this one under #HowTheGameHasChanged. There will never be another player like Charles “Victory” Faust.

Primary Resources; Charlie Faust – Society for American Baseball Research Biography, by Gabriel Schechter; Searching for Victory – The Story of Charles Victor(y) Faust, by Thomas S, Busch, Society for American Baseball Research, Research Journals Archives; Baseball-Reference.com; The Glory of Their Times, by Lawrence S. Ritter, McMillian and Company (1966).

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.