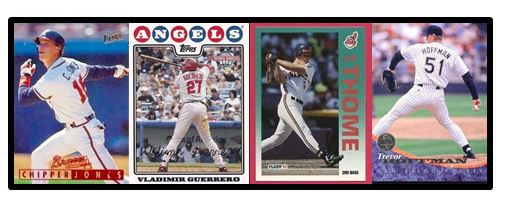

The 2018 Baseball Hall of Fame electees (via the traditional Baseball Writers Association of America ballot) have been announced – and four players were selected for 2018 induction by the BBWAA – Chipper Jones, Jim Thome, Vlad Guerrero and Trevor Hoffman. It was just the sixth time in HOF history that the traditional balloting has produced at least four inductees (four in 1939, 1947, 1955, 2015 and five in 1936, the Hall’s inaugural year). These four 2018 electees will join Modern Era Committee selections Jack Morris and Alan Trammell during the July 29 Induction Ceremony. Baseball Roundtable congratulates all six worthy inductees.

BBRT NOVEMBER PREDICTIONS – ON THE MARK

In early November, Baseball Roundtable made its 2018 BBWAA Balloting predictions – projecting the election of Chipper Jones, Jim Thome, Vlad Guerrero and Trevor Hoffman. For a complete look at the 2018 ballot, BBRT’s November predictions and how BBRT would have voted (if I had a ballot), click here.

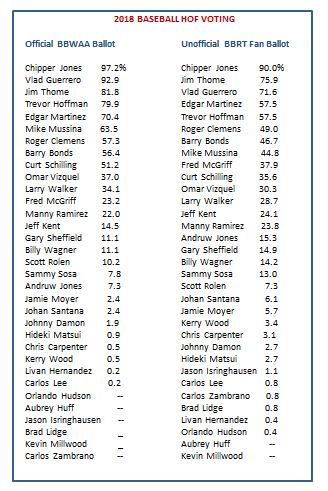

As regular readers may recall, Baseball Roundtable conducted an unofficial fan BB HOF ballot in November/December – inviting voters from among BBRT readers and a handful of Facebook groups dedicated to fans of the national pastime.

SPOILER ALERT:

Voters in the BBRT unofficial fan ballot gave the necessary 75 percent support to just two candidates – Chipper Jones and Jim Thome. Notably, players further down the ballot got more support in the fan vote (than in the official BBWAA balloting), while PED suspects got a bit less support in the fan ballot.

The order of finish in the BBRT fan balloting was remarkably similar to the BBWAA. The same five players finished in the top five positions. However, Guerrero, Hoffman and Martinez all got consisderably less support.

Although the order was mixed, nine players were included in the first ten spots on both ballots – and fourteen players appeared among the first fifteen vote-getters on both tallies. The most notable variation was Fred McGriff, who finished ninth on the fan ballot (37.9%), but 12th (23.2%) in the BBWAA voting.

Again, the most significant difference between the BBWAA and BBRT fan ballots is that only two players (Jones and Thome) reached the necessary 75 percent for election to the Hall in the fan ballot, as opposed to four in the BBWAA voting. Looking at the ballots, that variation can be partially explained by fans belonging to the “Voting-from-the-Heart” Cadre (an explanation of the voting cadres BBRT identified appears later in this post). This group of voters appears to be swayed at least partially by a home-town bias or loyalty to a favorite player. This seems evidenced by the fact that the BBWAA voting saw six players not receiving a single vote, while only two were shutout in the BBRT fan balloting. (Fourteen players failed to reach five percent on the BBWAA ballot, while twelve failed to reach that threshold in the unofficial fan ballot.)

We’ll look at the results in more detail, but here are a few high-level observations:

- A total of 271 fan ballots were cast – but ten were eliminated because they included votes for more than the allowed ten players (as many as 21 on one ballot). There were 422 BBWAA voters

- The average number of players voted for per ballot on the fan ballot was 7.9. BBWAA voters used an average of 8.5 of their ten allowed votes.

- 50 percent of the BBWAA voters used all ten avaliable votes; compared to 43 percent in the BBRT balloting.

- Only one player – Chpper Jones – was checked on 90 percent of the fan ballots. Both Jones and Vlad Guerrero topped 90 percent on the official BBWAA voting.

- In the BBRT fan balloting, only five players reached at least 50 percent, while nine reached that level in the BBWAA voting.

___________________________________________

Now, how about a look at what BBRT observed as “VOTER CADRES.”

The ballots and comments (form fans and BBWAA members( pointed to a half dozen voter “cadres” impacting BBRT fan balloting, most of which were also reflected in the BBWAA balloting. This is not a judgement on voter strategies, but rather just an observation on factors that appear to be influencing voting patterns and vote totals.

The Anti-PED Cadre

This group declines to vote for PED users or (depending on the strength of their opposition) those under various levels of suspicion. There continues to be enough of these voters to effectively block a significant number of PED-associated candidates from election. Yet, there still is enough support to keep them on the ballot, reducing the numbr of available votes for other candidates. (A bit of a Catch-22 here.) This cadre made its presence felt in both the BBWAA and BBRT balloting.

A FEW FAN COMMENTS ON PEDs

Here are a few comments from the BBRT unofficial fan ballot that shed some light on the depth and impact of this issue.

“I know baseball turned a blind eye in the steriod era, but I didn’t. Hammering Hank is the true home run king.” Luke … CA

“I voted the steroid users in because the HOF needs to have the conversation. The Mitchell Report showed that GM’s knew who was using … they were complicit. I was an A’s season ticketholder, they marketed Bash Brothers inflatable arms!” Bill … CA

“The ten-vote limit isn’t working. Voters who support PED-users take votes away from non-users on the ballot – and those who oppose PED-users keep suspected violators from being elected. Both sides lose.” Bob … MN

The Small-Hall Cadre

This cadre focuses on demanding the highest standards for election to the Hall of Fame – and tends to vote for very few (or even zero) candidates. This, by the way, is not a new approach. Back in 1988, for example, nine blank ballots were cast in the BBWAA voting. A Los Angeles Times article quoted New York Daily News reporter Phil Pepe (who sent in one of the nine blank ballots) as saying the Hall of Fame was “too crowded,” adding “I think to go in alongside Ruth, DiMaggio, Williams, Aaron, Cy Young, you have to be the cream of the cream. The more you erode the standards, the more the standards will be eroded.” (1) This cadre has a notable impact on elections, since each ballot a player is not named on requires three ballots to counter that omission.

The Ballot-Hierarchy Cadre

Member of this cadre most often draw a line between first-ballot and subsequent-ballot votes, demanding far more to secure first-ballot entry. It is part of the reason that we have never seen a unanimous selection. But the impact of the balloting does, in some cases, go further. In a column (after turning in a blank ballot in 2013), ESPN’s Howard Bryant wrote: “I believe in the hierarchy of the ballot, that the first ballot is different than the second or the tenth, that there is a special prestige to a player being voted in the first time he is eligible.” (2) The question is, “Do voters just withhold that first-, second- or other-ballot vote, or does it go to another candidate who meets the hierarchy test?” There also appears to be a group of voters who combine “Ballot-Hierarchy” with “Anti-PED,” withholding votes from PED suspects until later years of eligibility.

The Strategist Cadre

Somewhat related to the “Ballot Hierarchy” group – at least in impact – this group reasons that certain players are sure bets to get the required 75 percent (like Chipper Jones this year) and chooses not to add to the sure-thing margin, but rather cast that vote for a player they find deserving further down the ballot. This approach may actually improve the chances of additional electees (while also continuing to ensure we don’t see a unanimous selection). A subset of this group are those who note that certain players (in, for example, the 40 percent range), while NOT likely to reach 75 percent in a given year, ARE pretty much assured of adequate support to stay on the ballot. This subset witholds votes from those candidates and votes to protects those the would like to see on the ballot (but who are less “safe”).

The From-the-Heart Cadre

This group (which seemed to show up in the BBRT unofficial fan ballot) casts votes for a specific player (or players) further “down the board” either as a “fan” statement or to ensure that player does not fall off the ballot (get less than five percent). This strategy may cost deserving candidates votes and delay/preclude their election. A Minnesota fan voting in the unofficial BBRT balloting, commented “I was a little concerned about Johan Santana, so I looked for some players I would support who seemed safe for a return and dropped one of those votes to Santana.” Simiilarly, BBWAA voter Minnesota StarTribune sportswriter Patrick Ruesse indicated he voted for “Scott Rolen and Johan Santana to keep them on the ballot.” (5)

The Ten-Best Cadre

This group simply votes for whom they felt are the ten best players; regardless of the factors influencing any of the cadres already noted. (Well, in some cases it is the eight or nine candidates they feel are deserving.) A few provided comments on who they would have added if they had one, two or three more votes. New York Post Sportswriter Ken Davidoff, who used all ten of his allotted votes, indicated he would have “included as many as five more” had he been allowed. (3) CBS sportswriter Matt Snyder put it this way in a January 11 article, “I definitely want more than ten players from this ballot to make the Hall of Fame, but it feels wrong to game the ballot. My stance is to just vote for who I believe are the ten best candidates and let the chips fall where they may.” (4)

THE RULE

Voting shall be based on the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contributions to the team(s) the on which the player played.

Footnotes:

(1) Blank Hall of Fame ballot serves as protest … January 14, 1988; Associated Press

(2) Drawing a blank on a HOF ballot … January 9, 2013; Howard Bryant, ESPN Senior Writer; espn.com

(3) My crowded Hall of Fame ballot, with no regard for the ‘sacred place’ … January 20, 2018; Ken Davidoff; New York Post (nypost.com)

(4) Hall of Fame Roundtable: Should voters ‘game” the ballot to get more players in? … January 22, 2018; Matt Snyder; cbssports.com

(5) It’s a Hall voter’s prerogative to change mind … January 25, 2018; Patrick Reusse; StarTribune

A COUPLE OF BOBBLEHEADS SOON TO BE ON THE WAY

Baseball Roundtable conducted a random drawing from among those voting in the unofficial Hall of Fame fan ballot – and a follower from Georgia was selected to receive a pair of bobbleheads (Jack Morris and Bernie Williams). They will be shipped out as soon as I hear back with shipping info. (If you are a Baseball Roundtable FB follower and are from Georgia, check your FB messages – it might be you.)

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook Page here.

Member: The Society for American Baseball Research; the Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.