Baseball Roundtable is pleased to bring readers a guest post from Chris Moskowitz of Baseball Reviews – thebaseballreviews.com – a solid source of information and opinion on baseball equipment from bats, to gloves, to shoes and more. This youthful blogger is a lifelong baseball fan, who has played at the Recreational, Traveling Team, Competitive Club and High School level. He currently works for the Somerset Patriots (Bridgewater Township, New Jersey) of the Atlantic League (Independent). You’ll find a link to The Baseball Reviews web site on the right-hand side of the BBRT home page.

_______________________________________________

THE WEIRD BEGINNINGS OF BASEBALL

by Chris Moskowitiz … thebaseballreviews.com

Yes, baseball has developed into an amazing and almost perfect sport. It is fair, fun, and an awesome choice for exercise and competition at any level. This is exactly why it is America’s favorite pastime.

But baseball hasn’t always been so great. Imagine playing baseball with a bat that is curved, facing a pitcher just 15 yards away from home plate. Consider handling a hot line drive without the aid of a fielder’s glove or crouching behind the plate without a catcher’s mask. Or imagine how long a game would take if it took nine balls outside the strike zone to produce a walk. All of these things seem a little far-fetched today, but this is how it was at the beginning of baseball.

FIELDERS’ GLOVES

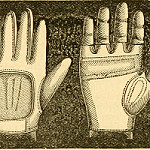

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images

Let’s talk about the gloves first. Gloves in baseball used to be nonexistent. Yes, you read that right, baseball gloves used to not be there to protect your hands. I would hate to have gone out to a position on the field in the era when there were no baseball gloves. A lot of people take something as simple as a baseball glove for granted. I know I did.

Imagine playing without a baseball glove and having to cleanly handle pop-ups or speeding grounders. It seems impossible. Especially when it’s cold out. Fall ball couldn’t be a thing in those times because there would have been too much pain in the joints of the hands of fielders. Imagine the sting you feel when you grab a sinking line drive with a glove. Now imagine the pain gloveless fielders must’ve gone through.

So how did they do it? Well, the answer is they would use smart techniques to stop the ball before fielding it. Some of these tactics include blocking the ball with their feet, slapping it down with their hands, or just letting it roll by, hoping the teammate behind them would stop it. I totally understand this, and would probably have done the same.

As the pain apparently mounted, innovation came. At first, fielders’ gloves looked pretty much like today’s batters’ gloves. Small, thin and not meant for catching or scooping. The main purpose of these earliest gloves was to knock the baseball down. Once the fielder could get the ball to stop, he could pick it up and throw it. Smart back then, now this is just a fielding exercise.

Fun Fact …

In the early days of baseball, there was considerable stigma attached to the use of a glove. One of the first group of confirmed players to don protective hand gear, first baseman Charlie Waitt, reportedly used a tan (near flesh-colored) glove, so as not to draw attention to the added gear. (Waitt played in the mid-1870s and early 1880s.)

The next step in innovation was to add the thumb and index finger pockets. I know that some baseball players like to stick their index finger out. I don’t. The main purpose for that is to gain more control of the glove. As you can imagine, the thumb and finger pockets represented a big step forward for baseball gloves – and the art of fielding.

The next version of the baseball glove had a “pocket” in the palm of the glove to actually enable fielders to catch and field ground balls. That advance was a real game changer.

Since these early innovations, gloves have continued to gain in quality and craftsmanship. New, more pliable and durable materials have been introduced; gloves have been shaped and sized for specific positions (catcher, first base, infield, outfield); and manufacturers have even added flashy colors that allow you to match your fielder’s glove to your team colors.

Fun fact …

Do you know who the creator of Spalding Sporting Goods (a popular sports supplies company) was? It was Albert Spalding, a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Red Sox and White Sox. Spalding – who led his league (the National Association and National League) in wins for all six of his full major league seasons. Spalding was well respected among players, and that respect was influential in the popularity of the baseball glove. When Spalding started wearing a baseball glove, a lot of others followed. After the popularity of the baseball glove started booming, he co-founded A.G. Spalding, a sporting goods company that is still very prominent today. He ran this company with his brother, Walter, and grew the company, while he grew baseball as well. For example, in 1874, Red Sox owner Harry Wright charged Spalding with organizing the first foriegn tour by American baseball players – who played both baseball and cricket overseas. Later, as a baseball executive, Spalding is also credited with such innovations as Spring Training, efforts to bring more discipline to the sport and with organizing additinal “world tours” to promote the game.

Also, did you know that the NBA official basketball is Spalding? Basketball wouldn’t be the same without baseball!

Note: Spalding played seven major league seasons (1871-1877), won 252 games and lost just 65, led his league in wins six times and put up career best numbers of 54-5, with a 1.59 earned run average in 1875.

BASEBALL BATS

Unlike baseball gloves, baseball bats were always in the picture, just not like we now know them. At first, for example, all baseball bats (for any level of play) were wood. The technology was not developed enough to have metal baseball bats. It was easy just to use a machine to spin a piece of wood into a bat.

Fun Fact …

In the early days of baseball – before there were equipment manufacturers – players used to make their own bats (without restricutions on size, weight, etc.). That must have made for some interesting sticks.

Did you know that some baseball bats used to have two knobs on them instead of one? We are all used to the one knob at the end of the bat, so the bat doesn’t fly out of your hands. When baseball was still in its early stages, some players used a two-knob bat, with the lower hand between the knobs and the upper hand resting on the top knob. Players like Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie (pictured below), who liked to “choke up” on the bat, were also known to use two-knob bats, resting the lower hand on the upper knob. I wonder just how comfortable that was and what the impact was on bat control and power.

Another weird thing with baseball bats actually still goes on today. Bone rubbing is a very old technique to fill in the pores of your baseball bat with a hard enough material. This meant that the bats broke less, and were considerably stronger, which was a big advancement. Baseball greats like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig applied this bone treatment to their prized bats for countless hours.

One of the most outrageous baseball bat designs ever was the curved bat shape of the 1890s. Not all of the bats of the era were curved, but the unusually shaped sticks were popular among some players. The purpose of this design was to enable hitters to put extra spin on the ball. The thought was that if you could increase spin, the ball would fly farther – and, when the fielder got to the ball, the strong spin would make it harder to keep in the hand or glove. This was true if the ball was hit perfectly with this bat, which was an extreme task because of the way the bat was shaped. The degree of ball spin was less coming off regular baseball bats, which is why some players liked this bat. History shows us this bat design did not make it very far and is now primarily an example of experimental equipment design from long ago.

CATCHERS’ MASKS

In the earliest days of the national pastime, about the only piece of protective gear a catcher had was a rubber mouthpiece (similar to what boxers use). Of course, at that time, catchers had more leeway in terms of positioning. Most stood well behind the hitters, grabbing pitches and foul tips on the bounce. As the rules changed, requiring third strikes to be caught on the fly, catchers moved closer to the plate – and more protection was needed.

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images

The catcher’s mask showed up in 1876 – a fencing mask modified by a fellow name Fred Thayer and used by the Harvard baseball squad. It was so popular (and much needed) that, by 1878, Thayer’s patented mask had secured a place in the popular A.G. Spalding Sporting Goods catalog. Over the years, protection for catchers has continued to improve – mitts, chest protectors, shin guards are all part of a modern-day catcher’s prized gear.

BASE ON BALLS

Not only has baseball equipment changed dramatically, we’ve also seen rules improvement from the early days of our national pastime. In the late 1870s, it took nine balls outside the striking zone to earn a walk. Imagine the effect of that rule on “pace of game.” In 1880, the figure was dropped to eight balls; it slid down to six in 1884; five in 1887; and the current four-ball rule came into play in 1889.

Fun Fact …

Here’s a fun, and kind of weird, fact. In 1887, baseball experimented with a “four strikes and you’re out” rule. This (what now seems weird) rule lasted only one season.

PITCHING DISTANCE

The last crazy part of baseball’s beginnings that I’ll share has to do with the distance between the pitcher and the batter. Nowadays, you’re probably used to the pitcher being 60-feet/six-inches away from home plate. However, that distance is lot more generous than the batter-to-pitcher path of baseball’s early days.

When baseball first started, the pitcher actually had no set length to pitch from. You could theoretically pitch from second base or just three-feet away. When baseball first “fixed” the pitching distance, the pitcher would stand 45-feet away from the batter. This seems like a pretty hazardous distance to me. It would be hard for any batter to avoid an errant (or purposeful) inside pitch and equally difficult for a pitcher to field a line drive smashed back at him.

The reaction time of a pitcher is one of the most important things in baseball. If the ball comes off the bat too fast or the pitcher is too close, the rules have to change. This is why the distance is now 60-feet/six-inches and also why we see bat regulations. One of the bat regulations used now is BBCOR – or “Batted Ball Coefficient of Restitution – a measure of how much energy is lost (retained) when the bat makes contact with the baseball.

Well, all of these things had to come before we could witness the almost perfect baseball that we know today. All of these advancements have helped to make baseball more comfortable, safer and more enjoyable for players and fans.

Hope you enjoyed this guest post and, if you have a deeper interest in the equipment that is shaping today’s game, you can check out our equipment reviews at thebaseballreviews.com

Primary Resources: Society for American Baseball Research; Baseball-Reference.com; Baseball-Almanac.com; Smithsonianmag.com; 19cbaseball.com

If you have some specific interests, here are links directly to related reviews.

BATS: Click here.

GLOVES: Click here.

CLEATS: Click here.

OTHER GEAR: Click here.

In addition, the “Guides” link has posts on everything from choosing a bat, to joining an adult league to caring for a baseball glove.

________________________________________________________

Baseball Roundtable tweets baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow/Like the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

More baseball commentary, blog post notifications, prizes.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

![[Ty Cobb, Detroit AL (baseball)] (LOC) by The Library of Congress Ty Cobb photo](https://baseballroundtable.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/18552310668_54380e2cbb_q_Ty-Cobb.jpg)