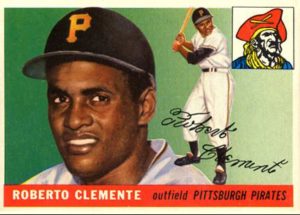

Robin Ventura, Jason Varitek, Todd Helton, Mark Teixeira, Jered Weaver, Alex Gordon. David Price, Buster Posey, Stephen Strasburg, Kris Bryant. What ballplayer wouldn’t want to be mentioned in the same breath as these stars? Well, a young outfielder with a perfect baseball name – Seth Michael Beer – and tremendous baseball potential already is.

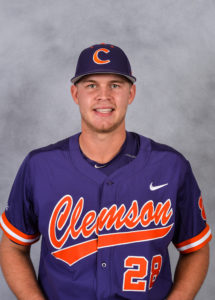

Seth Beer – first freshman Dick Howser Trophy winner – helped lead the Clemson Tigers to the 2016 ACC title. Photo: Courtesy Clemson University.

Playing right field and batting in the three-spot for 2016 Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) Champion Clemson University, the 6’3”, 200-pound Beer joined the previously noted MLB All Stars in earning the Dick Howser Trophy as the national college baseball player of the year. And, he did it in dramatic fashion. Not only did Beer become the first freshman to earn the recognition, he did it after leaving high school early to attend Clemson. Basically, he earned collegiate player of the year honors when he very well could have been playing his senior season at Lambert (GA) High School.

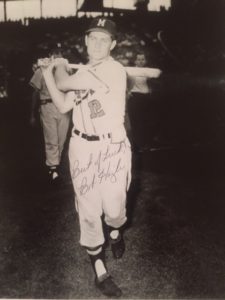

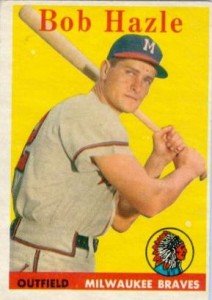

Now, as regular followers of Baseball Roundtable know, during the off-season, this blog has a tendency to look back nostalgically at what some members of my family call “antique baseball.” Witness recent posts on Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn (click here) and 1957 Braves’ hero Bob “Hurricane” Hazle (click here). In this post, however, I’d like to look toward the future – and share with readers a little bit about an individual who is truly a player to follow as he continues his college – and moves on to a major league – career.

THE NUMBERS

A lot of BBRT readers are deep into statistics, so let’s start our look at Seth Beer with a few numbers.

As a college freshman, Beer played in 62 games – hitting .369, with 13 doubles, 18 home runs, 70 RBI, 57 runs scored, 62 walks (versus 27 strikeouts) and 15 hit-by-pitches. He led Clemson to the Atlantic Coast Conference title, being selected team MVP – after leading the squad in batting average, home runs, slugging percentage, on-base percentage and outfield assists. Can I say it again – as a freshman.

High School – A Precursor

Seth Beer’s performance on the diamond for the Clemson Tigers should be no surprise. In two seasons of high school baseball, Beer hit .537, with 12 home runs, 61 RBI, 44 runs scored, 30 walks (15 strikeouts) in 48 games. As a pitcher, he went 3-1, with a 1.80 ERA, striking out more than a batter an inning. (High school stats from maxpreps.com.) Beer earned six high school athletic letters (three in baseball, two in football and two in swimming) and was a national high school All American in baseball as a sophomore and a junior.

THE CHARACTER

Then, of course, there is character. Majoring in Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, Beer was an Atlantic Coast Conference Academic Honor Roll Member and All-ACC Academic selection.

And, while he definitely has his sights set on a major league career (and cites his parents as the biggest influence in his life and baseball), Beer told BBRT that “After my playing career, I want to be involved in helping others, specifically with homeless shelters.”

Beer’s coach at Clemson, who has called Beer the best freshman he’s ever seen, also praised the young star’s work ethic and quiet leadership.

“Seth is more of a quiet leader and leader by example,” Clemson Coach Monte Lee said. “As he gets older, he will become more of a vocal leader. Players really look up to him because of his work ethic.”

Character is also reflected in Beer’s Dick Howser Trophy selection. In presenting the Award, DH Trophy Chair David Feaster said “Seth Beer truly deserves this national honor. His status as a national player of the year as a freshman is a history-making moment. In just a short time, he has exhibited the Dick Howser traits of excellent performance on the field, leadership, moral character and courage.”

ADDITIONAL RECOGNITION

I should emphasize here that the Dick Howser Trophy was not the only recognition Seth Beer earned as a college freshman. Here are just a few of the additional honors Beer received in his first season at Clemson:

- College Sports Madness Player of the Year (first freshman winner);

- First Team All American by American Baseball Coaches Association, Baseball America, College Sports Madness, D1Baseball, National College Baseball Writers Association, and Perfect Game;

- Atlantic Coast Conference Player of the Year (first freshman winner); and, of course;

- A host of awards reserved for college freshman, including National Freshman Player of the Year by Baseball America, College Sports Madness, D1Baseball and Perfect game, as well as several freshman All-American honors.

Baseball Roundtable is introducing readers to Seth Beer in this post because I believe he is a player and young man to watch – and that, some day, you will be able to see his baseball skills, leadership and positive character on a major league field near you. I might add (see the box below), the odds seem to be in his favor.

The Dick Howser Award

The Dick Howser Trophy was established in 1987 to honor the national college baseball player of the year. The Award is named after Dick Howser – twice an All American shortstop at Florida State University, an eight-season major league player (1961 All Star) and eight-season major league manager (1985 World Series Champion) – who passed away in 1987, at age 51, of brain cancer. From 1987-1998 the winner were selected by the American Baseball Coaches Association. Since 1999, the National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association has made the selection.

How much of an indicator of future success is this honor? Of the 28 winners (Brooks Kieschnick of the University of Texas is the only two-time winner):

24 became MLB First-Round draft picks;

24 went on to play in the major leagues;

13 became MLB All Stars;

Three became Rookies of the Year – Jason Jennings, Buster Posey, Kris Bryant;

Two were selected first overall in the MLB draft – David Price, Stephen Strasburg;

One went on to win a league MVP Award – Buster Posey; and

One captured a Cy Young Award – David Price.

BBRT’s advice? Track Seth Beer’s sophomore season – and beyond. If you are in a fantasy league with “reserve keepers,” consider drafting him now. Start saving now for an MLB jersey with “Beer” and his number proudly displayed on the back.

In the meantime, BBRT says congratulations to Clemson and Seth Beer on a tremendous 2016 season – and the best of luck for the coming campaign.

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Follow me there for notification of new posts.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research (SABR); The Baseball Reliquary; Baseball Bloggers Alliance.