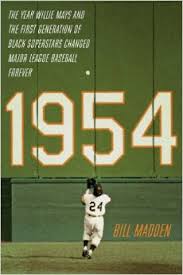

1954 – The Year Willie Mays and the First Generation of Black Superstars Changed Baseball Forever

By Bill Madden

Da Capo Press 2014

$25.99

Baseball is often referred to as America’s most literary sport, and there is no doubt that Bill Madden has contributed to that reputation. In 2010, Madden was recognized with the J.G. Taylor Spink Award – the highest honor given by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America – and enshrined in the writers’ wing of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Fortunately, for fans of baseball and its literature, Madden did not choose to rest on his laurels. Instead, he continues to add to his reputation, which gets another boost from latest book: 1954 – The Year Willie Mays and the First Generation of Black Superstars Changed Baseball Forever.

Within the back drop of the 1954 pennant races and World Series, Madden gives readers a look at how attitudes toward race – in baseball and across American society – were changing. Consider what was going in baseball in 1954:

- Larry Doby, the first black player in the American League (Indians, 1947), led the AL in home runs and RBI while helping Cleveland achieve an 111-43 record – breaking a five-season Yankee stranglehold, not just on the AL pennant, but also on the World Series championship.

- Willie Mays returned from military service to top the NL with a .345 average and capture the MVP Award, while leading the Giants to the NL title.

- Hank Aaron who, in 1953, had led the Class A Sally League in batting average, RBI, runs and hits, made the jump from Class to the majors, as well as the move from second base to the outfield – where he would join Billy Bruton, the 1953 NL stolen base leader (and first black player to make the major leagues without previous Negro League experience).

- The Cubs began the season with the first all-black, shortstop-second base, double play combo – Ernie Banks and Gene Baker, who had both seen action when the team integrated in late in 1953.

- On July 17, 1954, the Brooklyn Dodgers broke baseball’s unspoken, but implied, racial quota by starting a line up with more blacks than whites.

- The World Series, for the first time ever, saw black players on both teams’ rosters.

Madden deals with these and other historically and socially significant on-the-field achievements and advancements, and also gives readers a look at the intolerance and indignities black players faced in the early 1950s. He recounts the roadblocks many highly talented black players faced in even getting to the majors (keep in mind, as Spring Training opened in 1954, only eight of the major leagues sixteen teams had integrated). And, things were not much easier once a player made the leap to the majors (and found on-field success). Black players found themselves having to stay in separate hotels or negotiating the right to stay in the team’s chosen hotel only if the they agreed to stay out of such areas as the lobby, dining room or swimming pool. Madden, through observation and interviews, provides unique insight in how different players – Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Hank Aaron, Don Newcombe and others – handled these (and even more glaring) slights, inequities and prejudices. (I found Madden’s reporting of the fiercely negative reaction to the the first Sports Illustrated cover to feature an athlete of color – April 11, 1955, with Leo Durocher, Durocher’s wife, actress Laraine Day and Willie Mays – particularly telling.)

While 1954 provides an important (and, I am sure for many, eye-opening) social commentary on the times, it also includes plenty of baseball action, told in the words of the participants, news coverage of the day and Madden’s own captivating prose. There are accounts of key games, great plays and clutch hits that carry the reader through the 1954 season and World Series.

Overall, 1954 gives the reader the “feel” of the season and the times. You can feel the anger and frustration of black players striving not just for recognition, but basic respect and fairness, as well as the tension of on-field rivalries and tough pennant races. As you read, you also get a feel for the churn and change taking place in the game (on the field, in the club house and in the executive offices). Ultimately, 1954 provides insight into how baseball in the 1950s – despite its flaws and shortcomings – was actually out in front of the curve when it came to the acceptance of black Americans.

And, there are “back stories” as well.

- How – had the Red Sox been less reluctant to integrate or the Giants willing to part with just $100 a month more – baseball might have seen Willie Mays sharing the outfield with Ted Williams or Hank Aaron.

- The fact that, with just one game left in the season, the NL batting race saw three players separated by .0004: Don Mueller at .3426, Duke Snider at .3425 and Willie Mays at .3422.

- The tough, grind-it-out attitude of the players in the 1950s, illustrated particularly well in an injured Al Rosen‘s 3-hit, 2-homer, five-RBI performance in the 1954 All Star Game.

- The negative reaction of players, managers and coaches to a 1954 rule change that required players to bring their gloves into the dugout when their team came to bat. (It had been baseball custom until then for fielders to leave their gloves on the field when they came in to bat, and just pick them up when back on defense.)

- Mickey Mantle’s own assessment of the “Who was New York’s best center fielder – “Willie (Mays), Mickey (Mantle) or the Duke (Snider)?” question.

- Minnie Minoso’s thoughts on why he led the AL in hit-by-pitches ten times from 1951-1960.

1954 is a solid addition to Madden’s work and to the overall library of baseball literature. It provides readers not only with a look at one of baseball’s most exciting seasons, but also insight into the racial tensions being felt not just across the national past time, but across the nation. It works on many levels, as a sports book, history book and social commentary. It is a fun, but also thought-provoking, summer read for baseball fans.

Other books by Bill Madden:

Steinbrenner: The Last Lion of Baseball

Pride of October: What It Was to Be Young and a Yankee

Zim, A Baseball Life (with Don Zimmer)

Damned Yankees: Choas, Confusion, and Craziness in the Steinbrenner Era (with Moss Klien)