Gotta watch this six-year-old Little Leaguer – five at bats, five first pitch home runs.

Move over Babe Ruth, there is a new Sultan of Swat on the rise.

Archives for July 2013

Wow! Unprecedented Power Display!

Old Guys Rule – Franco is Their King

Jason Giambi of the Cleveland Indian yesterday punched his 436th career home run in dramatic fashion. It was a ninth-inning, pinch-hit, walk-off homer that gave the Indian a 3-2 win over the visiting Chicago White Sox. It also made Giambi, in his 19th major league season, the oldest player to hit a walk-off homer; at 42 years, 202 days. The record had been held by Hank Aaron, who hit a walk-off in 1976 at 42 years, 157 days of age. It was Giambi’s 7 homer of the season, to go with a .194 average and 24 RBI.

Giambi might hold the only home run record not in the pocket of the ageless wonder – Julio Franco. Franco is the oldest player to homer in a MLB game. He turned the trick just shy of his 49th birthday (48 years, 254 days), hitting a two-run shot off Arizona’s Randy Johnson as Franco’s Mets topped the Diamondbacks 5-3. (Franco started at first base in that game and went two-for-three.) Franco is also the oldest player to hit a grand slam (46 years, 308 days) – connecting as a pinch hitter for the Atlanta Braves in a 7-2 win over the Marlins on June 27, 2005. He’s the oldest player to record a multi-homer game, belting a pair of homers on June 18, 2005 (age 46 years, 299 days), as his Atlanta Braves topped the Reds at Great American Ball Park. Franco started at first base and went two-for-four with two homers and three RBI. And, finally, he’s also the oldest player to hit a pinch hit home run, in the eighth inning of a Mets’ 7-2 win over the Padres at San Diego (April 20, 2006 – 47 years, 240 days old). Note: Only 25 MLB home runs have been hit by players 45 or older – and 20 of those belong to Franco.

In this post, BBRT would also like to reflect on another Julio Franco record – the oldest player ever put in as a pinch runner (47 year, 340 days). It came on July 29, 2006, when the Mets’ first baseman and cleanup hitter Carlos Delgado was hit by a pitch in the top of the third inning in the New Yorkers’ 11-3 win at Atlanta. Franco came in as a pinch runner (stayed in at first base, going two-for-three) and promptly stole second base, going to third on an errant throw. Wow? The old guy still had wheels. (he’s the second-oldest player to steal a base, but that’s for another post.)

Now, here’s BBRT’s blatant pitch – Julio Franco for the BB Hall of Fame. Let’s look at his career. Franco came to the big leagues in 1982 at age 23. From 1982 to 1994, he played primarily as a middle infielder and DH for the Phillies, Indians, Rangers and White Sox – making three All Star teams (MVP of the 1990 All Star game) and leading the league in hitting .341 for the Rangers in 1991 (went he collected 201 hits, 15 homers, 78 RBI, 108 runs scored and 36 steals.). In 1994, when the remainder of the season was lost to a strike, Franco was in the midst of his best season. After 112 games, he was hitting .319, with 138 hits, 20 home runs, 98 RBI, 72 runs scored, and eight steals.

Franco was determined to stay active and signed to play in Japan with the Pacific League Chiba Lotte Marines In the 1995 Japanese season, Franco hit .306 and won the league’s equivalent of the Gold Glove at first base. Franco returned to MLB in 1996, joining the Cleveland Indians and going .322-14-76 in 112 games. In August 1997, the Indians released Franco –who was hitting .284-3-25 at the time, and he finished the season with the Brewers by hitting .241 in 14 games with Milwaukee.

In 1998, at age 39, Franco was back in Japan playing for Chiba Lotte. Then in 1999, he celebrated his fortieth year by hitting for a .423 average in the Mexican League and getting one more MLB late season at bat with the Marlins.

As he moved into his forties, Franco was far from finished as a player. He played in South Korea in 2000 (age 41) and then was back in the Mexican League in 2001 (Angelopolis Tigers), where stellar play earned him a spot on the Atlanta Braves roster. From 2001 to 2007, the ageless wonder – professional hitter and pretty darn good first sacker – played for the Braves and Mets. He finally retired from the field in 2008, while playing for the Tigres de Quintana Roo of the Mexican League (where he hit .250 in 36 games.)

Why the Hall of Fame? In addition to the accomplishments above, in 23 MLB seasons, Franco hit .298, with 2,586 hits, a .298 average, 173 homers, 1,285 runs, 1,194 RBI and 281 stolen bases. He also collected 618 minor league (U.S) hits, 316 in the Mexican League, 286 in Japan, 267 in the Dominican Winter League and 156 in South Korea. Clearly, Julio Franco is a player whose skills were evident across time and geography and whose contributions and character deserve HOF consideration.

Follow me on Twitter @DavidBBRT

Twitter – Something New for BBRT

BBRT is giving Twitter a try. Follow @DavidBBRT. I’ll be tweeting baseball haiku, trivia questions and answers, comments on plays/players of the day and random thoughts. Here’s an example – my first two haiku tweets.

BBRT is giving Twitter a try. Follow @DavidBBRT. I’ll be tweeting baseball haiku, trivia questions and answers, comments on plays/players of the day and random thoughts. Here’s an example – my first two haiku tweets.

Six to four to three

Graceful end to the inning

American ballet

and

Braun admits “mistake”

More names, shame, soon to follow

Game will survive

Ted Williams – Voice for Hall of Fame Integration

“The other day, Willie Mays hit his five-hundred-and-twenty-second home run. He has gone past me, and he’s pushing, and I say to him, “Go get ’em, Willie.” Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel. Not just to be as good as someone else, but to be better. This is the nature of man and the name of the game. I hope that one day Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall of Fame as symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.”

Ted Williams’ Basesball Hall of Fame Induction speech

July 25, 1966

It was 47 years ago today that Ted Williams surprised the audience at his Baseball Hall of Fame induction by urging the inclusion of Negro League players in the Hall of Fame. His sincere, vocal, publicly voiced vote of support is credited with providing an important first foot in the (HOF) door for Negro League stars. The impact of Williams’ groundbreaking comments is held in such esteem that the speech is among the exhibits at the Negro League Baseball Museum.

Five years later (1971,), the Hall of Fame created a special committee to consider players who had been at least 10-year veterans of the Negro Leagues and were ineligible for regular Hall election. The special committee was dissolved in 1977 and action on Negro Leaguers was transferred to the Hall of Fame’s’ Veterans Committee.

It is likely no coincidence that Satchel Paige, specifically mentioned in Williams’ induction speech and often referred to by Williams as “the greatest pitcher in baseball,” was inducted in the first year Negro Leaguers were considered – nor that, in 1972, Josh Gibson (also mentioned in Williams’ speech) joined Paige in the Hall (along with Buck Leonard).

Note: In addition to Williams’ support, the 1970 publication of Robert Peterson’s “Only the Ball was White” is credited with keeping the pressure on the Hall of Fame.

Victory for Negro Leaguers (and baseball in BBRT’s estimation) did not come easy. The initial plan was for a “separate-but-equal” display, along the lines of the Ford C. Frick Award for baseball broadcasters. This approach, however, came under considerable criticism, with Satchel Paige himself saying he would accept no less than induction into the mainstream Hall of Fame. As a result of the firestorm, Negro League players were admitted on the same basis as their Major League peers.

Here are a few additional Negro League/Baseball Hall of Fame/Ted Williams factoids:

– Ted Williams’ Boston Red Sox were the last team to integrate, with infielder Pumpsie Green joining the Sox on July 21, 1959.

– Former Negro Leaguers – who also played in MLB – elected on the traditional HOF ballots include: Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Willie Mays, and Jackie Robinson.

– Effa Manley, co-owner and business manager of the Newark Eagles in the Negro National League, was the first woman elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

– Hank Aaron was the last Negro league player to play as a regular in Major League Baseball.

– Minnie Miñoso was the last Negro league player to play in a Major League game, appearing in two games for the 1980 Chicago White Sox.

– Buck O’Neil was the last former Negro league player to appear in a professional game at any level when he made two appearances (drawing two intentional walks one for each team) in the Northern League All-Star Game in 2006. O’Neil, 94-years-old at the time, started the game as a member of the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks and led off the top of the first for the league’s West All Stars. He drew an intentional walk, was removed for a pinch runner and was quickly “traded” to the Kansas City T-Bones, which enabled O’Neil to lead off the bottom of the first for the East (drawing a second intentional pass). O’Neil was the second oldest player to appear in a professional baseball game. On June 19, 1999, another former Negro League star – 96-year-old Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe – started on the mound for the Northern League’s Schaumburg Flyers (against the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks) and threw one pitch (a ball).

– In 1993,Ted Williams (with his son John Henry Williams) launched the Ted Williams (baseball) Card Company.’ Publicity surrounding the launch pointed out that Williams had a hand in selecting the players and compiling the back-of-the-card comments. The set consisted primarily of retired All Stars, great hitters and Negro League stars). At the time, Williams commented, “I am especially proud that through our Barrier Breakers subset we can pay tribute to the greats of the Negro Leagues.”

Here’s your list of Negro Leaguers selected to the Hall of Fame (not including former Negro Leaguers elected on the regular ballot).

Satchel Paige (1971)

Josh Gibson (1972)

Buck Leonard (1972)

Monte Irvin (1973)

Cool Papa Bell (1974)

Judy Johnson (1975)

Oscar Charleston (1976)

Martin Dihigo (1977)

Pop Lloyd (1977)

Rube Foster (1981)

Ray Dandridge (1987)

Leon Day (1995)

Bill Foster (1996)

Willie Wells (1997)

Bullet Rogan (1998)

Joe Williams (1999)

Turkey Stearnes (2000)

Hilton Smith, Hilton (2001)

Ray Brown (2006)

Willard Brown (2006)

Andy Cooper (2006)

Frank Grant (2006)

Pete Hill (2006)

Biz Mackey (2006)

Effa Manley (2006)

Jose Mendez (2006)

Alex Pompez (2006)

Cum Posey (2006)

Luis Santop (2006)

Mule Suttles (2006)

Ben Taylor (2006)

Cristobal Torriente (2006)

Sol White (2006)

J.L. Wilkinson (2006)

Jud Wilson (2006)

Note: The significant induction of the Negro Leaguers in 2006 followed up an extensive study and special election (by a 12-person Special Committee on Negro Leagues chaired by former Commissioner Faye Vincent).

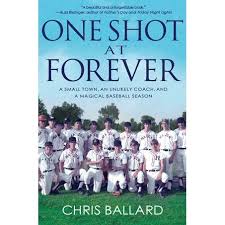

One Shot At Forever – A True and Truly Entertaining Tale

One Shot At Forever

One Shot At Forever

A Small Town, An Unlikely Coach, And A Magical Baseball Season

By Chris Ballard

Hyperion Books, 2012, $14.99

One Shot At Forever is appropriately subtitled: A Small Town, An Unlikely Coach, And A Magical Baseball Season. If you didn’t know it was true, the tale told in this spirited (and thoroughly enjoyable) book by Sports Illustrated senior writer Chris Ballard would be unbelievable – instead, it is unforgettable. BBRT thinks readers – and not just baseball fans – will find One Shot At Forever easy to read, hard to put down and impossible to forget.

Like most classic sports tales, it’s a story of overcoming great adversity. But it’s much more than that, it’s also an extraordinary story about relationships, rebellion and loyalty – for Macon, Illinois, is no ordinary community, their coach is no ordinary coach and their team is no ordinary team. And, Ballard captures it all in compelling prose that pulls you along through the action that takes place on the field and off.

Overcoming adversity? The Macon high baseball team – the Ironmen – makes its improbable way all the way to the 1971 Illinois State Championship game. In that pursuit, Macon faces schools with enrollments not just ten, but as much twenty, times Macon High’s 250 students. And, the budget and equipment – and even administrative support – disparities are just as large. (This was back in 1971, before Illinois high school tournaments placed schools in various classes by size.)

The community? Macon is a town of about 1,200 – conservative, rural and (as Ballard puts it) stuck in the Eisenhower era. and facing not only a drought that threatens the local economy, but an emerging social era that troubles many residents (antiwar protests, the 18-year-old vote, the founding of Greenpeace, hippies, communes.)

The coach? Lynn Sweet ( coach and English teacher) is not exactly a fit with Macon’s attitudes and values. His long hair, fu Manchu mustache and progressive approach to life, learning and baseball earn him comparisons with Frank Zappa, an unkempt Beatle, Abbie Hoffman in a ball suit and, by one sportswriter “a pinch of bad Mexican hombre, a fun-loving Joe Pepitone and a collegiate peacenik.” Further, in attempts to oust him (as teacher and coach) at more than one school board meeting, community members label sweet everything from hippie to peacenik to a communist.

The team? I don’t want to spoil the reader’s fun, so here are just a few snapshots of what makes the Macon Ironmen of 1970-71 different (and establishes them as Coach Sweet’s team). Due to a limited budget, they wear well worn, mismatched uniforms from three different Macon High eras; as they arrive at games, they can usually be heard singing “Yellow Submarine” on the bus; a number of players choose to wear peace symbols on their hats (which do not disguise their ever-lengthening hair); and they take pregame warm-ups to the sounds of the rock opera “Jesus Christ Superstar” blaring from a boom box on the sidelines. Getting the picture? And, remember, this is a true story.

Coach Sweet is the protagonist of One Shot at Forever and his approach to authority – and life in general – is established early. The day (in 1965) he is hired to teach English at Macon High (his first teaching job), the principal warns Sweet “There are three taverns in town and, as teachers, we don’t drink in them. To set a good example, you understand.” Sweet nods in understanding and then manages to sample the cold brew at Cole’s Tavern, Claire’s Place and the Nite Owl all in that same afternoon.

Sweet’s approach to authority and convention extend into the classroom, where he quickly replaces traditional desks with round tables and chairs (better exchange of ideas); decorates the walls with posters of the Rolling Stones, Grace Slick and Bob Dylan; scraps the traditional grammar books, announces unconventional assignments (like having the youngsters write their own obituaries) and develops a reading list that for many Macon parents seems a bit too progressive (or even subversive). He even sets up a barbeque grill outside his class, so students can join him in grilling over lunch. As a teacher, Sweet, proves to be a polarizing force (key members of the administration and many parents are suspicious of his methods, while some parents are pleased that their children are learning, while having fun). This class room controversy is just a foreshadowing of what is to come on the baseball diamond.

Sweet’s turn to coach the baseball team (he will be their third coach in three years) comes in 1970. On the day of their first practice under their new coach, only fourteen players show up (by contrast, one of the teams they will eventually play in the 1971 state tournament has more than 400 freshman show up for annual team tryouts.). Looking over the team, a couple of facts became clear, “Those that weren’t small were scrawny. And those that weren’t scrawny were small.”

Given the turnout, Sweet makes a quick judgment. “I’ve got good news, boys, you’ve all made the team.” He also outlines his approach to coaching: few, if any, rules; practice is optional; no wind sprints, punishments or speeches; steal when you want; and decide among yourselves who will play where. (It should be noted that Sweet, while without previous coaching experience, is not without baseball acumen. He is a long time fan of the Cubs and played baseball on military bases as a boy and on a local semipro team while in college.)

Coach Sweet soon finds that this team of farm boys (as the team develops under Sweet, they are alternately referred to as hippies or hicks) are smooth and talented. They have been neighbors, school mates and team mates all their lives and they play well together. All they need, in Sweet’s view is “Someone to believe in them.” And as the season(s), and the book progress, we learn about the strengths, weaknesses and motivations that each player brings to the Ironmen, as well as how Sweet works to build and protect their sometimes fragile teenage egos. Sweet’s belief in, and genuine affection for his team (and their true commitment to each other, their school and town), are what carries the Macon Ironmen to success in the face significant odds.

BBRT won’t give away the whole story, it is just too much fun to read, but here are just a few examples of the adversity the Ironmen must face:

– After a successful 1970 season, the team is dropped from the playoffs due to a roster technicality (while no culprit is ever identified, some believed was deliberate sabotage).

– Sweet is fired as coach before the 1971 season, rehired as parents and players protest.

– Devoid of budget and low on equipment, the team usually has no more than four or five bats (this in in the age of wooden bats). In one playoff game, against a talented, big school fast-baller, the team has three bats break. Down to just one bat, the principal and student equipment manager rush (during the game) to a local hardware store to purchase four more bats. As the Ironmen await more equipment, Sweet has each upcoming hitter return the lone bat to the equipment bag and then rummage around in the bag (as if searching for the right stick), so as not to alert the opposition to their predicament.

– Steve “Shark’ Shartzer, the team’s best player and most energizing field leader, is forced to play the final games of the 1971 Illinois State Tournament with a well-taped broken hand.

The Ironmen’s remarkable run is well-documented, with each player – expertly handled by Coach Sweet – making unique contributions to the team’s success along the way. Ballard manages to give us a meaningful look not just into the players’ performance, but their personalities as individuals and, maybe even more important, their role in shaping the personality of the Ironmen as a team.

In the final section of the book, Ballard returns to Macon four decades after that magical season and visits with the coach and players, providing further evidence of how much they all mean to each other and to the community and how that “magical season” had a lasting impact on their lives. Even this part of the book offers insight and inspiration, as the later life activities range from Sweet’s turning his land into a wildlife refuge under a state program called “Acres for Wildlife” to Ironmen outfielder Brian Snitker’s rise to third base coach for the Atlanta Braves.

One Shot at Forever is an entertaining and inspiring read. The story and its telling (in Ballard’s prose) have joyous momentum. Notably, that momentum continues. Ballard’s story of Coach Sweet and the Macon Ironmen originally appeared as a Sport Illustrated article (The Magical Season of the Macon Ironmen, June 2010 issue), it surged forward as Ballard’s 2012 book and has continued its momentum with Legendary Entertainment (which gave us the Jackie Robinson film “42”) purchasing the movie rights.

BBRT’s advice – buy the book, see the movie, enjoy and share the story (and the stories within the story).

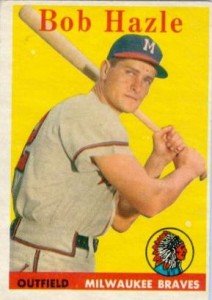

Move Over DiMaggio and Puig – Hurricane Hazle Is Here

Cuban defector Yasiel Puig created quite a stir in MLB, hitting at a .436 pace over his first MLB month (26 games), with seven home runs and 16 RBI. Even BBRT succumbed to Puig-O-Mania (see post of July 2), joining in the rush to compare Puig’s first month with that of Joe DiMaggio (.381-4-28 in 26 games).

All of this, plus the influx of new, young stars in the 2013 All Star game, got BBRT to thinking about one of the heroes of my youth. It was late July 1957, I was ten-years-old and a baseball (and Milwaukee Braves) fanatic. The Braves were in a tight pennant race with the Cardinals, Dodgers and Reds. Milwaukee’s chances, however, seemed to be dimming as center fielder and lead-off man Billy Bruton went on the disabled list in mid-July with a season-ending knee injury. The Braves looked to patch together an outfield, calling on Andy Pafko and calling up 26-year-old outfielder Bob “Hurricane’ Hazle, who was hitting .279, with 12 homers and 58 RBI at Triple A Wichita. (Hazle, who began his minor league career at age 19, had a .287 minor league career batting average, with 66 home runs in seven seasons and 771 games, when called up to the Braves.)

All of this, plus the influx of new, young stars in the 2013 All Star game, got BBRT to thinking about one of the heroes of my youth. It was late July 1957, I was ten-years-old and a baseball (and Milwaukee Braves) fanatic. The Braves were in a tight pennant race with the Cardinals, Dodgers and Reds. Milwaukee’s chances, however, seemed to be dimming as center fielder and lead-off man Billy Bruton went on the disabled list in mid-July with a season-ending knee injury. The Braves looked to patch together an outfield, calling on Andy Pafko and calling up 26-year-old outfielder Bob “Hurricane’ Hazle, who was hitting .279, with 12 homers and 58 RBI at Triple A Wichita. (Hazle, who began his minor league career at age 19, had a .287 minor league career batting average, with 66 home runs in seven seasons and 771 games, when called up to the Braves.)

Hazle got into his first game on July 29, when he went to the plate (as a pinch hitter) and dropped down a sacrifice bunt in the fifth inning of a 9-8 Braves’ win over the Giants. At the time, the Braves stood at 57-41, tied with the Cardinals for first place and 1 ½ games ahead of the Dodgers – but Hazle’s status and the Braves’ fortunes were about to change. Hazle got his first start in the Braves’ outfield two days later (going one-for-four with a double and an RBI) and thirty days and 20 games played after that, he marked the one month anniversary of his first Braves’ plate appearance by boasting a .507 average, 33 hits, four home runs and 22 RBI. In the 18 games Hazle started in the first 30 days after his initial plate appearance, Milwaukee went 14-4. That included four wins and two losses against the rival Cardinals, in which Hazle hit .478 with one home run and eight RBI.

Hazle played a total 41 games for the Braves in 1957, hitting .403, with 54 hits, 26 runs scored, twelve doubles, six home runs and 27 RBI. He also walked 18 times, four intentionally. And the Braves, tied for first when Hazle played in his first game, ended up finishing eight games ahead of the Cardinals (and went on to win the 1957 World Series). The Braves had a .582 winning percentage when Hazle first took the field for them that season – and played .679 ball the rest of the way. Hazle finished fourth in the 1957 Rookie of the Year balloting, despite playing in only 41 games.

Hazle played a total 41 games for the Braves in 1957, hitting .403, with 54 hits, 26 runs scored, twelve doubles, six home runs and 27 RBI. He also walked 18 times, four intentionally. And the Braves, tied for first when Hazle played in his first game, ended up finishing eight games ahead of the Cardinals (and went on to win the 1957 World Series). The Braves had a .582 winning percentage when Hazle first took the field for them that season – and played .679 ball the rest of the way. Hazle finished fourth in the 1957 Rookie of the Year balloting, despite playing in only 41 games.

Eddie Mathews, third baseman (and future Hall of Famer) on the `57 Braves, summed up Hazle’s pennant drive performance in his book Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime, writing “What can you say about Hurricane Hazle? He came up to the Braves at the end of July, and for the rest of the year nobody could get him out. I’ve never seen a guy as hot as he was – ever. He was something else to behold … I don’t know what happens to suddenly make a minor league ballplayer into Babe Ruth, but Hazle was right out of ‘The Twilight Zone.’”

Note: Hazle’s first month with the Braves does differ a bit from DiMaggio and Puig. Hazle, still a rookie, had garnered 13 at bats (three hits) with the Cincinnati Reds after a late 1955 call-up.

Just as a hurricane blows over, however, Hazle’s gale-force MLB career was short lived. Hazle was hit in the head by a pitch during Spring Training in 1958, suffered an ankle injury early in the season and, on May 7, was hit in the head again – this time by a pitch from the Cardinals’ Larry Jackson. Hazle was hospitalized for about a week. He returned to action, but was hitting only .179 on May 24, when he was traded (cash and a player to be named later) to the Tigers. The move came as the Braves’ Billy Bruton was cleared for a return to the active roster.

Hazle hit .241, with two homers and five RBI in 43 games for the Tigers. He was sent to the minors (AAA) in 1959 and played in Charleston, Birmingham and Little Rock in 1959-60. He hit .266, with four homers and 41 RBI at Triple A in 1959 and .291-9-57 at Double A in 1960 before retiring from baseball in April 1961.

In his brief (110 games) MLB career, Hazle hit .310, with nine home runs and 37 RBI. For a couple of months at the end of the 1957 season, however, Hurricane Hazle stormed through National League pitching with success seldom seen from a rookie – or a veteran. In the process, he energized the Braves, changed the pennant race and helped bring Milwaukee its first NL and World Series Champion. Not a bad legacy for someone who logged only 110 MLB games.

MLB Changing Of The Guard – Players We’ll All Love to Watch

The finals of yesterday’s All Star Celebration Home Run Derby featured two second-year major leaguers – with the A’s Yeonis Cespedes topping the Nationals’ Bryce Harper. The fact that the two finalists have a combined 405 major league games and 73 career home runs to their credit underscores a positive trend – the emergence of a cadre of young, talented players who promise an exciting, new post-steroids (hopefully) era and aura for our national past time. Although BBRT often likes to reflect on baseball’s past glories, in this post, I’d like to take at some emerging young “stars” that BBRT looks forward to watching in the future. I’ve arbitrarily defined young as 24-years-old and under, and will start with a look at a few 2013 All Stars who meet the criteria.

Bryce Harper, Nationals’ outfielder, age 20.

Harper, the 2012 NL Rookie of the Year, is already on his second All Star team. He’s had some injury problems this season (58 games played), but still stands at .264, with 13 home runs, 29 RBI and six stolen bases. In 2012, as a 19-year-old, Harper (6’2”, 230 lbs.) hit .270, with 22 home runs, 59 RBI and 18 stolen bases.

Mike Trout, Angels’ outfielder, age 21.

Trout made his debut in July of 2011 (at age 19). In 2012, his first full MLB season, he won AL Rookie of the Year honors and made his first All Star team. He finished the season, with a .326 average, 30 home runs, 83 RBI, while leading the AL in runs scored (129) and stolen bases (49). Trout (6’2”, 230 lbs.) is again on the AL All Star squad, with 2013 stats that include a .322 average, 15 home runs, 59 RBI, 65 runs scored and 21 steals.

Manny Machado, Orioles’ third base, age 21.

Machado debuted with the Orioles in early August 2012, going .262-7-26 in 51 games. The 6’2”, 185-pound, 2013 All Star continues to show good power, leading the AL in doubles (39) at the All Star break – along with a .310 average, 7 homers and 45 RBI. It will be interesting to see if Machado can maintain his pace. In 219 minor league games, he hit .263, with 23 home runs and 114 RBI.

Jean Segura, Brewers’ shortstop, age 23.

Segura made his MLB debut last July 24 and hit just .259, with no homers, 14 RBI and seven steals in 45 games. A .313 hitter (with 139 steals) in 399 minor league games, Segura came into his own at the major league level this year, earning an All Star berth by leading the NL in hits (121) at the break. The 5’10”, 200-pounder’s 2013 line is: .325, 11 homers, 36 RBI, 54 runs and 27 steals in 92 games.

Pat Corbin, Diamondbacks’ LHP, age 23.

Corbin made his MLB debut last April and went 6-8, 2.54 in 2012. A 2013 All Star, Corbin stands at 11-1, 2.35 with 109 strikeouts in 130 1/3 innings pitched. Corbin’s (6’2”, 185-pounds) minor league stats (80 games, 79 starts) are 31-16, 3.78 with 404 strikeouts in 430 2/3 innings.

Matt Harvey, Mets RHP, age 24.

The 6’4”, 225-pound starter made his MLB debut in 2012, going 3-5, 2.73 with 156 strikeouts in 135 2/3 innings. This season, Harvey earned his way onto the All Star squad with a 7-2 record, a 2.35 ERA and an NL-leading 147 strikeouts in 130 innings pitched.

There are also some pretty exciting “under-25ers,” who did not make the 2013 All Star Game – but deserve watching going forward.

Yasiel Puig, Dodgers’ outfielder, age 22.

Puig, who defected from Cuba in 2012, came up to the Dodgers on June 3. In 38 games, Puig (6’3”, 240-pounds) has hit .391, with 8 home runs, 19 RBI and 5 steals.

Shelby Miller, Cardinals’ RHP, age 22.

The (6’3”, 215-pound) rookie – just six appearances in 2012 – has posted a 9-6 record with a .2.92 ERA, 29 walks and 112 strikeouts in 18 starts. In 78 minor league starts, Miller went 29-21, 3.73 and struck out 472 batters in 383 2/3 innings.

Jose Altuve, Astros’ second baseman, age 23.

At 23, Altuve is in his third major league season (called up in July 2011). The 5’5” 175-pound infielder was an All Star in 2012, when he hit .290, with seven homers, 37 RBI, 80 runs scored and 33 steals. He remains a steady and solid performer in 2013, with a .280 average, three homers, 28 RBI, 37 runs and 21 steals in 86 games.

There’s a look at some of the “under-25” players that should be exciting to watch in the future. Now, let’s briefly touch on a few players who fell just outside the “under-25” limitation, but also reflect baseball’s “changing of the guard.”

Aroldis Chapman, Red’s closer, age 25.

At 25, and in his fourth MLB season and second All Star game, Chapman (of the 104 mph fastball) took a 3-3 record, with a 2.79 ERA, 21 saves and 64 strikeouts in 38 2/3 innings into the break. In 2012, his first full year as closer, he notched 38 saves, with a 1.51 ERA and 122 strikeouts in 71 2/3 innings.

Paul Goldschmidt, Diamondbacks’ first baseman, age 25.

A 2013 All Star, Goldschmidt seems to just keep getting better. As a rookie, in 2011, he hit .250, with eight homers and 26 RBI in 48 games. In 2012, he played 145 games, with a .286-20-82 line (and 18 steals). This season, he is hitting .313 and already has 21 home runs and an NL-leading 77 RBI, along with nine stolen bases.

Pedro Alvarez, Pirates’ third baseman, age 26.

Another 2013 All Star, at 26 Alvarez is in his fourth MLB season. A .240 career hitter, Alvarez has shown tape-measure power. In 2012, he finished with 30 home runs and 85 RBI. At the break this year, he stands at 24 homers and 62 RBI.

Lance Lynn, Cardinals’ RHP, age 26.

Lynn made the All Star as a rookie in 2012, when he went 18-7, 3.78. Through the break in 2013, he is 11-4, 4.00.

Buster Posey, Giants’ catcher, age 26.

Hard to think of Posey as one of the up and coming youngsters, but – despite being in his fifth MLB season – he is only 26 (and already a Rookie of the Year, NL MVP, batting champ and two-time All Star). At the break, Posey (a .316 hitter in 398 MLB games) sits at .325-13-56.

Chris Davis, Orioles’ first baseman, age 27.

A 2013 All Star, Davis makes this list at age 27 because he only became a player to watch in 2012. In his first four MLB seasons, Davis averaged 74 games, a .251 batting average, 11 home runs and 34 RBI. In 2012, he broke out with .270-33-85 and, this year, he went into the All Star break leading all of baseball with 37 home runs, boasted a .315 average and was second only to Miguel Cabrera with 93 RBI.

So, there are some of the “youngsters” BBRT thinks will make for some pretty good baseball over the next five to ten years. There are others, of course (feel free to make suggestions in the comments), but these are a few that stand out for me.

One final player, BBRT will be keeping an eye on is Pirates’ closer Jason Grilli, who seems to have found himself at age 36 (actually at age 34, but I’ll get to that). In his first 11 MLB seasons, Grilli had five saves and an ERA north of 4.00. The 2013 All Star, this year has an NL-leading 29 saves, 1.99 ERA, nine walks and 63 strikeouts in 40 2/3 innings.

Grilli’s is an interesting and inspiring story. He made his major league debut in 2000 (Florida Marlins) and between 2000 and 2009 spent time with the Marlins, White Sox, Tigers and Rockies. He suffered a severe knee injury during Spring Training 2010 (with the Indians), missed the entire season and ultimately filed for free agency. In January 2011, Grilli signed a minor league contract with the Philadelphia Phillies and pitched well at Triple A before being released on July 20 (and signing a minor league deal with the Pirates the very next day). Since joining the Pirates, Grilli has pitched 135 games, with a 2.52 ERA and 190 strikeouts in 132 innings. BBRT will be watching for the Pirates to break their 20-year string losing seasons and make it to the playoffs – behind a league-leading performance in saves by Grilli.

For The Record – At The Break

Just a few days ago, Tigers’ third baseman Miguel Cabrera made headlines as the first MLB player to record 30 home runs and 90 RBIs by the All Star break – making him the sole member of an exclusive, if somewhat arbitrary, MLB “club.” I use the term arbitrary because, while 30/90 are nice round numbers, neither are pre-All Star break records. More on that later, but BBRT can report that, thanks to a four-RBI performance on Sunday, Orioles’ first sacker Chris Davis – the main obstacle to a repeat Triple Crown by Cabrera – has doubled the size of the pre-All Star 30/90 club.

As we head into the break Cabrera stands at .365, with 30 home runs and 95 RBI – leading MLB in average and RBI and second (to Davis) in home runs. Notably, Cabrera’s numbers are up in all three categories over those at the break in last year’s Triple Crown season (.324-18-71 at the 86-game mark). Davis goes into the break at .316, with 37 home runs (leading MLB) and 93 RBI (second only to Cabrera).

Now about those AS break records. Davis’ 37 home runs are second to Barry Bonds, who had 39 HRs at the 2001 break. Also at 37 homers at the break are Mark McGwire in 1998 and Reggie Jackson in 1969. (For a complete look at the 30-homers at-the-break club, see BBRT’s post of July 7, just add Cabrera to the list).

The record for RBI at the break is 103, by the Tigers’ Hank Greenberg in 1935 (at the 76-game mark). Greenberg finished the season at 170 RBI. The Tiger, the first to carry the nickname “Hammerin’ Hank,” was an RBI machine, leading the AL four times in his 13 MLB seasons and topping 130 in a season five times, with high of 183 in 1937. In his peak years (1936-40), Greenberg averaged better than an RBI per game (777 RBI in 759 games). The only other player to top 100 RBI at the break was Juan Gonzalez of the Rangers, who had 101 at the 1998 All Star break (87 games in), finishing the season at 157. Gonzalez only led the league once in his 17 seasons, but did top 130 RBI four times.

Also making waves at the break is 41-year-old Mariners’ outfielder Raul Ibanez, who goes into the break at .267, with 24 home runs and 56 RBI – with the HR and RBI totals at the break the highest ever for a forty-plus player. Ibanez is fast closing in on Ted Williams’ record of 29 homers in a full season for a player after his fortieth birthday. In his final season (1960), at age 41, Williams hit 29 homers in 113 games. Ibanez, who was an All Star only once (2009, when he hit a career-high 34 homers for the Phillies), is not on the All Star team. He has 295 home runs to date, in an 18-year MLB career.

Another “oldie-but-goodie” who will be at the All Star Game is Yankee closer Mariano Rivera. The 43-year-old Rivera has an MLB record 638 saves. This season he has 30 saves and a 1.83 ERA – the saves represent his highest total ever at the break. Rivera, in his final season, is going out in style. The record for saves at the AS break, by the way, belongs to Francisco Rodriguez, who had 35 saves for the Angels at the break in 2008 – on his way to an MLB record 62-save season. In his peak four seasons (2005-2008), Rodriguez ran up 194 saves. John Smoltz is close behind (and holds the NL record for saves at the break) with 34 saves for the Braves at the 2003 All Star break. Smoltz, a full-time reliever for only three of his 22 seasons, recorded 144 saves from 2002-2004. For you trivia buffs, Smoltz and Dennis Eckersley are the only two MLB pitchers to record seasons of 20 or more wins as a starter and 50 or more saves as a reliever. This season, Jim Johnson of the Orioles is the saves leader at the break with 33 saves to go with a 2-7 record and a 3.71 ERA.

A couple of other All Star break facts. Rickey Henderson holds the record for stolen bases at the break. In 1982, while with the A’s and on the way to an MLB single season record 130 steals, Henderson had 84 stolen bags at the break. This year’s stolen base leader at the break is the Red Sox’ Jacoby Ellsbury with 36.

When it comes to wins at the AS break, your leader is the White Sox’ Wilbur Wood, who had 18 wins at the break in 1973. (He also had 14 losses, was not selected for the All Star Team and finished the season 24-20.)

The most wins for a pitcher who made the All Star team is 17 by the A’s Vida Blue (17-3 at the 1971 break) and the Tigers’ Mickey Lolich (17-6 at the 1972 break). Blue finished 24-8 on the year, while Lolich ended up 22-14. This year’s wins leaders at the break are Tampa Bay’s Matt Moore (13-3) and the Tigers’ Max Scherzer (13-1).

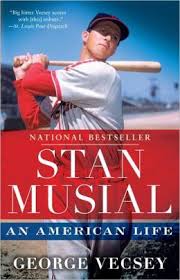

Stan Musial – An American Life

STAN MUSIAL – An American Life

STAN MUSIAL – An American Life

By George Vecsey

2011

Ballantine Books. $26 (paperback $16)

Stan Musial – An American Life provides ample evidence that “nice guys can finish first,” but, perhaps, won’t be remembered as long (or revered as much) as their more controversial counterparts. In 1999, Major League Baseball launched a fan vote to select the top twenty-five players of the twentieth century. Saint Louis Cardinals’ outfielder/first baseman Stan Musial – a 20-time All Star, seven-time batting champ, three-time MVP and more – did not make the top twenty-five (in fact, he did not even make the top ten outfielders).

What were Musial’s credentials? It starts with a 22-year MLB career with the aforementioned 20 All Star selections, three MVP Awards and seven batting titles. He also “finished first” in the NL in games played nine times; hits six times; runs five times; doubles eight times; triples five times; RBI twice; and total bases six times. He ended his career with 3,630 hits and a .331 career average. He collected 1,377 extra base hits (475 home runs), and struck out only 696 times – never striking out 50 times in a season, and topping forty strikeouts only three times.

So, why didn’t the fan vote place Stan Musial among the top twenty-five? What made him in this instance (unlike such peers as Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams) forgettable?

Most speculate it’s because Stan Musial’s “story” was less compelling than his statistics. He was substance without flash, competence without controversy, results without razzle-dazzle. Musial was married to his high school sweetheart for more than 70 years, was never tossed out of a game, was an astute businessman who did not squander his money, never forgot his Catholic and Polish-American roots,and consistently avoided confrontation and controversy. In short, while he was long on professionalism, he was deemed to be short on personality.

Fortunately, Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig had anticipated there would be “oversights” in the 1999 fan vote and had established a knowledgeable committee to add five players to the All–Century Team. Their first addition was Stan Musial (followed by Christy Mathewson, Warren Spahn, Honus Wagner and Lefty Grove).

Notably, Musial remained true to form in handling the fans’ slight. When reminded of how he was added to the All-Century Team, Musial (as always) took the high road. “I wasn’t upset. Not really. There are 100 million fans, and only three million of them voted. It’s what the fans wanted, and I’m happy to be here. It’s human nature to look at your own generation. It’s hard to analyze what happened fifty-sixty years ago.”

In Stan Musial –An American Life, New York Times sports columnist and best-selling author George Vecsey gives us a deeper look at Stan Musial. It’s not your usual baseball biography – filled with on-field conflict and off-field controversy. As you might expect, Musial comes off in the book as more interesting than exciting – and, in fact, the tales from Musial’s off-field life seem more compelling than what takes place on the field. (BBRT would have liked to have seen a bit more on Musial’s on-field play and passion in the book.)

Still, readers will find plenty of anecdotes they will want to share. In the process, you will also gain some insight into the many individuals – some celebrities/some night – that became part of Musial’s life story. Here are a few snippets that BBRT found interesting.

It’s pretty common knowledge that Musial started out as a pitcher and moved to outfield full-time after an arm injury. What is less known is how well Musial did throw. In his final season on the mound, playing for Daytona Beach (Class D) in 1940, Musial went 18-5, 2.62 with 223 innings pitched, 19 complete games and 176 strikeouts. The minor league team carried only a 14-man rosters, so pitchers often found themselves in the outfield, where young Musial hit .311 in 113 games (and injured his arm diving for a ball).

Stan Musial was given his nickname Stan “THE MAN” not by Cardinals’ fans, but rather by Brooklyn Dodgers’ fans – out of respect for the way he manhandled Brooklyn pitching over the years.

Musial never forget his Polish and Catholic roots, making multiple trips to Poland; meeting with Nobel Prize winner Lech Walesa and even enjoying dinner and a small group private mass at the Vatican with Pope John Paul II (in 1988). One of Musial’s travel mates on the trip described the Hall of Famer’s approach to the Pope as like “an altar boy in awe of the Pontiff.”

Musial was s staunch Democratic, hitting the presidential campaign trail for John Kennedy in 1960 as part of a group that included: Byron White (former football player and later Supreme Court Justice); James A. Michener (who became a close and long-time friend and traveling companion of Musial); Arthur Schlesinger; Ethel Kennedy; Joan Kennedy; actor Jeff Chandler; and actress Angie Dickinson. (Musial was also a George McGovern supporter in 1972).

Musial was a horrible poker player, a not-so-good magician and a decent harmonica player (who often, serenaded fans with “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

Musial trimmed his eyelashes to help him see the ball better.

Musial, always accommodating to the fans, began carrying autographed photos of himself to hand out, an idea he picked up during lunch with actor John Wayne.

Musial was always ready to model his unique corkscrew stance – even in later years, when he used his cane as a bat.

In presenting a mostly positive (openly admiring) picture of Stan the Man, Vecsey does not gloss over all criticism – acknowledging Musial’s apparent avoidance of controversy and confrontation, particularly as it related to racial issues (or even general players’ rights) within baseball. Vecsey notes that some players, while seeing Musial as an inherently just man, felt he could have taken a stronger stance in relation to the issues facing baseball in his playing days. As the Cardinals’ Curt Flood put it: “We admired Musial as an athlete. We liked him as a man. There was no conscious harm to him. He was just unfathomably naïve.”

Ultimately, Stan Musial – An American Life is an appropriate tribute to Stan the Man – a confident, gracious individual, who never forgot his humble roots and who choose quiet efficiency and inner optimism over controversy and the potential pitfalls of the limelight.

BBRT feels privileged to have seen Musial play – and to have felt the tension and anticipation that rippled across the stands when he went into his unique corkscrew stance. BBRT wishes that tension could have emerged from the pages of Stan Musial – but, ultimately, the book reflects the inner character of its subject. It’s a good read, especially if your interest is in the “man” and not just the ballplayer.

BBRT’s favorite anecdote from the book? One of Musial’s team mates is reported to have told Stan that he felt so good, “I feel like going four-for-four today.” To which Musial quickly replied, “Hell, I feel like that every day.” And, as the statistics tell us, justifiably so.

30 Homers Before the Break – Here’s the “Club of Clubbers”

In 2012, the Orioles’ Chris Davis, at age 26, had a career year – finishing with a .270 average and a career-high 33 home runs and 85 RBI. In 2013, the 6’ 3”, 230-pound first baseman is hitting .324 and has already matched his 33 round trippers and 85 RBI of the 2012 season – with a week of games to go before the All Star break. Here’s some background on the “30-HR before the break” club and Davis’ targets for the coming week.

First, only six players have hit more than 33 homers before the break – led by Barry Bonds 39 in 2007, when he finished with all-time MLB high of 73 dingers for the Giants.

Reggie Jackson and Mark McGwire are next with 37 pre-All Star Game homers. Jackson for the A’s in 1969 (he finished with 47) and McGwire for the Cardinals in 1998 (finishing with 70). Ken Griffey, Jr. of the Mariners had 35 at the break in 1998 (finishing with 56), as did Louis Gonzalez of the Diamondbacks in 2001 (ending the season with 57 homers). Frank Howard of Senators reached 34 homers by the 1969 All Star break (finishing with 48). We can expect Davis to move up this list over the coming week, although Bonds’ 39 seems out of reach.

Overall, 30 or more home runs before the All Star break has been achieved 34 times, by 26 different players, in MLB history (including Davis this year.) Mark McGwire has done it most often – in 1987, 1997, 1998, and 2000. The only others to reach the thirty mark at break time more than once are Ken Griffey, Jr. (three times); and Willie Stargell, Sammy Sosa and Barry Bonds (twice each). Perhaps, the most surprising member of this “club of clubbers” is the Orioles’ Brady Anderson – who had 30 HRs at the break in 1996, on his way to a 50-homer season. In his 15-year career, Anderson totaled 210 homers and his second-highest season total was 24.

McGwire is the only player to reach the 30 homer-mark before the break in both leagues (as well as for more than one team). He achieved the feat with the A’s in in 1987 and 1997 and the Cardinals in 1998 and 2000. McGwire holds some other distinctions among members of this club. He is the only player to be traded during a season in which he reached the 30-homer level by the break. In 1997, McGwire had 33 homers at the All Star break and hit one more for the A’s before they traded him (July 31) to the Cardinals (where he went on to hit 24 more home runs). McGwire is also the only rookie to reach 30 homers by the All Star break, with 33 in 1987, when the 23-year-old A’s rookie hit 49 and captured Rookie of the Year honors.

By decade, the 1950’s saw 30 homers reached before the break once; the 1960’s – five times; the 1970’s – four times; the 1980’s – three times; the 1990’s – 12 times; 2000-2009 – seven times; 2010-13 – twice. 1998 was the single most prolific year for “thirty-before-the break,” with the Cardinals’ McGwire going into the break with 37 HRs, the Mariners’ Griffey, Jr. at 35; the Cubs’ Sammy Sosa at 30; and the Padres Greg Vaughn at 30.

Here’s the full list of players with 30 or more homers at the break, with season-ending total in parenthesis.

39 HRs … Barry Bonds, Giants, 2001 (73)

37 … Reggie Jackson, A’s, 1969 (47)

37 … Mark McGwire, Cardinals, 1998 (70)

35 … Luis Gonzalez, Diamond backs, 2001 (57)

35 … Ken Griffey Jr., Mariners, 1998 (56)

34 … Frank Howard, Senators, 1969 (48)

33 and counting, Chris Davis, Orioles, 2013

33 … Roger Maris, Yankees, 1961 (61)

33 … Sammy Sosa, Cubs, 1998 (66)

33 … Ken Griffey Jr., Mariners, 1994 (40)

33 … Matt Williams, Giants, 1994 (43)

33 … Mark McGwire, A’s, 1987 (49)

32 … Albert Pujols, Cardinals, 2009 (47)

32 … Sammy Sosa, Cubs, 1999 (63)

32 … Frank Thomas, White Sox, 1994 (38)

31 … Jose Bautista, Blue Jays, 2011 (43)

31 … David Ortiz, Red Sox, 2006 (54)

31… Jose Canseco, Devil Rays, 1999 (34)

31 … Mark McGwire, A’s & Cardinals, 1997 (58)

31 … Kevin Mitchell, Giants, 1989 (47)

31 … Mike Schmidt, Phillies, 1979 (45)

31 … Willie Mays, Giants, 1954 (41)

30 … Alex Rodriguez , Yankees, 2007 (54)

30 … Jim Thome, White Sox, 2006 (42)

30 … Barry Bonds, Giants, 2003 (45)

30 … Mark McGwire, Cardinals, 2000 (32)

30 … Greg Vaughn, Padres, 1998 (50)

30 … Ken Griffey Jr., Mariners, 1997 (56)

30 … Brady Anderson, Orioles, 1996 (50)

30 … Dave Kingman, Mets, 1976 (37)

30 … Willie Stargell, Pirates 30, 1973 (44)

30 … Willie Stargell, Pirates, 1971 (48)

30 … Willie McCovey, Giants, 1969 (45)

30 … Harmon Killebrew, Twins, 1964 (49)