It’s early June, and that means it’s time for Baseball Roundtable’s May Wrap up – a look at the stats and stories that caught The Roundtable’s attention over the past month, as well as The Roundtable’s Players and Pitchers of the Month, Trot Index and more. (The Roundtable usually publiches the Wrap Up on the first of the month, but a computer clash led to lost files a delay.) Just a few of May’s ‘highlights that you will find in this post:

- A record-tying ten solo home runs in a game (Royals/Orioles);

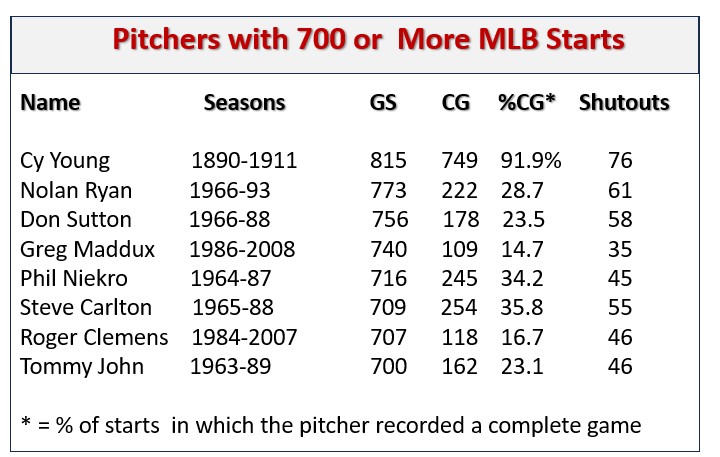

- A “Maddux” – shutout of less than 100 pitches – with a Maddux-record 13 strikeouts (Tarik Skubal);

- A 21-0 shutout win (Padres/Rockies);

- A hitter with 100+ May at bats raking at a .400+ pace (Freddie Freeman);

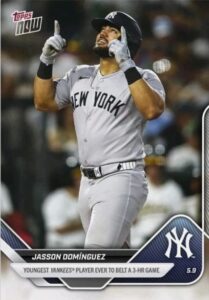

- A player (a rookie) becoming the first MLBer to achieve a three-homer game, a contest with homers both left- and right-handed, a Grand Slam and a walk-off homer in a single calendar month (Jasson Dominguez);

- 2025’s first Immaculate inning (Cal Quantrill);

- Bryce Harper‘s 1,000th RBI and Kyle Schwarber‘s 300th home run;

- A player tying the record for most times hit by a pitch in an inning and a game (CJ Abrams);

- Chris Sale becoming the quickest MLB hurler to reach 2,500 strikeouts;

- A team scoring nine runs before making the first out of a game (Nationals/Diamondbacks); and

- More

See the Highlights Section for these stories and more.

—-PLAYERS AND PITCHERS OF THE MONTH … MAY 2025—-

NATIONAL LEAGUE

Player of the Month … Shohei Ohtani, DH, Dodgers

Photo: All-Pro Reels from District of Columbia, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

While I tend to assign some value to playing a defensive position, you cannot ignore Ohtani’s MLB-leading 15 May home runs. He also drove in 27 May tallies (fourth in MLB, second in the NL) and scored an MLB-best 31 runs, while averaging .309 for the month. In addition. Ohtani ‘s 21 May extra-base hits (five doubles, one triple and 15 homers) led MLB and his .782 slugging percentage was second only to the Yankees’ Aaron Judge (among players with at least 75 May at bats). Ohtani’s month included ten multi-hit games and a thirteen-game span (May 3-16) during which he hit .404-9-19.

Honorable Mentions: Dodgers’ 1B Freddie Freeman hit .410 for the month (highest among players with at least 75 May at bats) and led MLB with 43 May hits. He hit safely in 22 of 27 May games. Cubs’ CF Pete Crow-Armstrong hit .269, with nine home runs and an NL-leading 29 May RBI. He also scored 20 runs and stole five bases in seven attempts. Nationals’ LF James Wood put up a .333-7-23 line for May.

Pitcher of the Month – Robbie Ray, LHP, Giants

I really thought Zack Wheeler would coast in with this one. After four May starts, he was 4-0, 0.68, with 31 strikeouts and only six walks. Then, in his final start of the month (May 29), he gave up six runs in 5 1/3 innings (with four walks and six strikeouts) in a 6-2 loss to the Braves and suddenly 4-0, 0.68 became 4-1, 2.24. That opened the door for a close race between Robbie Ray and the Reds’ Andrew Abbott. Ray tied for the MLB lead in wins for the month at 4-1 (in six starts), while Abbott was 3-0 in six starts. Ray put up a solid 1.38 ERA, but Abbott was even better with an MLB-best (among pitchers with at least 25 May innings) 0.55. Digging deeper, Ray bested Abbott in WHIP 0.87 to 0.98 and average against (.169 to .190). Ray also had a slight edge in strikeouts to walks (45 K / 8 BB to Abbott’s 33 K / 10 BB. Plus Ray went a little deeper in games (39 innings in six starts to Abbott’s 32 2/3 innings in six outings). Overall, slight edge, for me, to Ray.

I really thought Zack Wheeler would coast in with this one. After four May starts, he was 4-0, 0.68, with 31 strikeouts and only six walks. Then, in his final start of the month (May 29), he gave up six runs in 5 1/3 innings (with four walks and six strikeouts) in a 6-2 loss to the Braves and suddenly 4-0, 0.68 became 4-1, 2.24. That opened the door for a close race between Robbie Ray and the Reds’ Andrew Abbott. Ray tied for the MLB lead in wins for the month at 4-1 (in six starts), while Abbott was 3-0 in six starts. Ray put up a solid 1.38 ERA, but Abbott was even better with an MLB-best (among pitchers with at least 25 May innings) 0.55. Digging deeper, Ray bested Abbott in WHIP 0.87 to 0.98 and average against (.169 to .190). Ray also had a slight edge in strikeouts to walks (45 K / 8 BB to Abbott’s 33 K / 10 BB. Plus Ray went a little deeper in games (39 innings in six starts to Abbott’s 32 2/3 innings in six outings). Overall, slight edge, for me, to Ray.

Honorable Mentions: Andrew Abbott, LHP, Reds (see paragraph above.) Zack Wheeler, RHP, Phillies (see paragraph above). Matthew Boyd, LHP, Cubs, who went 3-0. 3.54 in May, gets a nod for putting up 34 strikeouts against just two walks – in 28 May innings.

AMERICAN LEAGUE

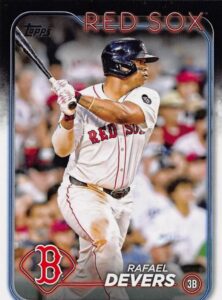

Player of the Month – Rafael Devers, DH, Red Sox

Devers led all major leaguers with 33 May RBI, to go with a .356 average and seven home runs. He was third in the AL hits with 37 and tied for the MLB lead in walks with 22. Devers’ .468 on-base percentage was tops among players with at least 75 May at bats. On May 23, he went four-for-six, with two home runs and eight RBI, as the Red Sox topped the Orioles 19-8. It was one of his ten multi-RBI May games.

Devers led all major leaguers with 33 May RBI, to go with a .356 average and seven home runs. He was third in the AL hits with 37 and tied for the MLB lead in walks with 22. Devers’ .468 on-base percentage was tops among players with at least 75 May at bats. On May 23, he went four-for-six, with two home runs and eight RBI, as the Red Sox topped the Orioles 19-8. It was one of his ten multi-RBI May games.

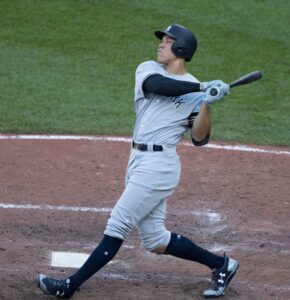

Honorable Mentions: The Mariners’ Cal Raleigh not only handled the heavy behind-the-plate duties, he led the AL in home runs with 12, while hitting .304 and driving in 26 runs. Yankees’ RF Aaron Judge hit .364 for the month, with eleven home runs (second in the AL), 18 RBI and an AL-leading 25 May runs scored. Guardians’ 3B Jose Ramirez went .386-5-14 for the month, with 22 runs scored and an AL-leading (tied) 39 base hits.

Pitcher of the Month – Tarik Skubal, RHP, Tigers

Photo: Jeffrey Hyde from Bryan, TX, United States, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Skubal racked up an MLB-leading 59 strikeouts in 41 May innings (2-0, 2.20 record), while walking just two batters. His month include one shutout – a 94-pitch, no-walk, 13- strikeout, two-hitter in a 5-0 win over division rival Guardians.

Honorable Mentions: Kris Bubic, LHP, Royals, went 3-0 in five May starts and put up a miniscule 0.56 ERA (the lowest among AL pitchers with at least 25 May innings). He did not give up more than one run in any of his five starts. He fanned 33 batters (eight walks) in 32 1/3 innings. Twins’ reliever righty Jhoan Duran appeared in 15 May games and put up four wins (one loss) and seven saves – as well as a tidy 0.60 ERA (one earned run in 15 innings). Veteran Carlos Rodon, LHP, Yankees went 3-0, 1.47 in five starts and Rangers’ righty Nathan Eovaldi went 2-1, 0.68 in five stats.

Surprise of the Month – Carlos Narvaez C, Red Sox

Narvaez signed (Yankees) as a teenager, out of Venezuela, in 2015. In eight minor-league seasons, he hit .250-47-237. He did have a brief call up to the Yankees in 2024 (.231-0-0 in six games). In December of 2024, Narvaez (noted for his defensive skills) was traded to the Red Sox, and most expected him to compete for the spot as Connor Wong’s backup. He made the team out of Spring Training and a new door was opened when Wong fractured his left pinkie finger early in the season. In March/April, Narvaez flashed his defensive skills and hit .218-3-8 in 22 games. In May, his bat surprised a lot of people (and earned this spot) – as he went .356-2-9 in 22 games.

Honorable Mention: SS Jacob Wilson of the A’s was a 2023 first-round pick (sixth overall), so his success is less of a surprise. What is a bit surprising is how quickly he found major-league success. A little background. In three seasons at Grand Canyon University, Wilson hit .361-22-155 in 155 games. Then, he hit .401 in two minor-league seasons (79 games) working bis way up from rookie-level to Triple-A. He was called up to the A’s in July of 2024 and hit .250-0-3 in 28 games. This March/April, he turned it up a notch (.325-3-15) and, in May, he was even better (.366-4-16), with an AL-leading (tied) 39 base hits. No surprise he’s living up to his promise, just surprising that he got there so fast.

____________________________________________________

THE TROT INDEX … A REGULAR BASEBALL ROUNDTABLE FEATURE

Through May 30, 34.5% of the MLB season’s plate appearances ended in a trot (back to the dugout, around the bases, to first base). We’re talking about strikeouts, home runs, walks, hit by pitch and catcher’s interference – all outcomes that are, basically, devoid of action on the base paths or in the field. Here’s the breakout: strikeouts (21.9%); walks (8.6%); home runs (2.9%); HBP (1.0%); catcher’s interference (less than 1%).

The 35.0% basically mirrors the 35.1% through April in 2024 (perhaps we’ve plateaued and the Index no longer serves a purpose). I also looked into full-year Trot Index figures for the years I have been a fan: 34.9% in 2024; 30.3% in 2010; 29.9% in 2000; 31.7% in 1990; 23.1% in 1980; 27.0% in 1970; 25.1% in 1960; and 22.8% in 1950.

__________________________________________________

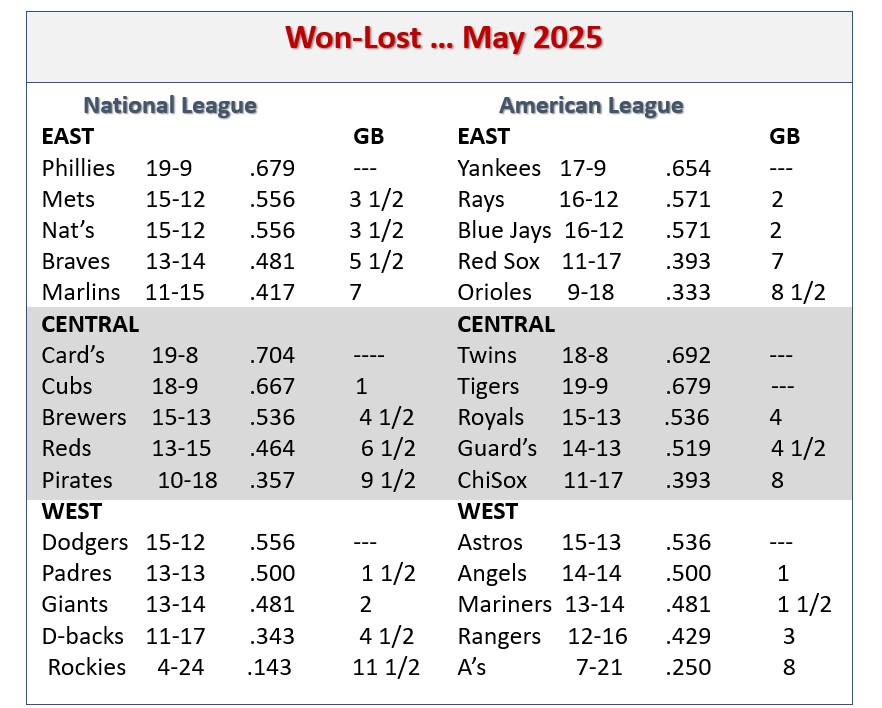

A few random observations:

- The Giants and Rangers were the only teams with ERAs under 3.00 – and both had sub-.500 records for the month.

- The Cardinals were the the only team to play .700+ ball – and they did it despite scoring the 11th most runs and giving up the eighth fewest.

- The Twins’ 18 May wins included a 13-game winning streak (longest in the majors this season) in which they outscored their opponents 68-29.

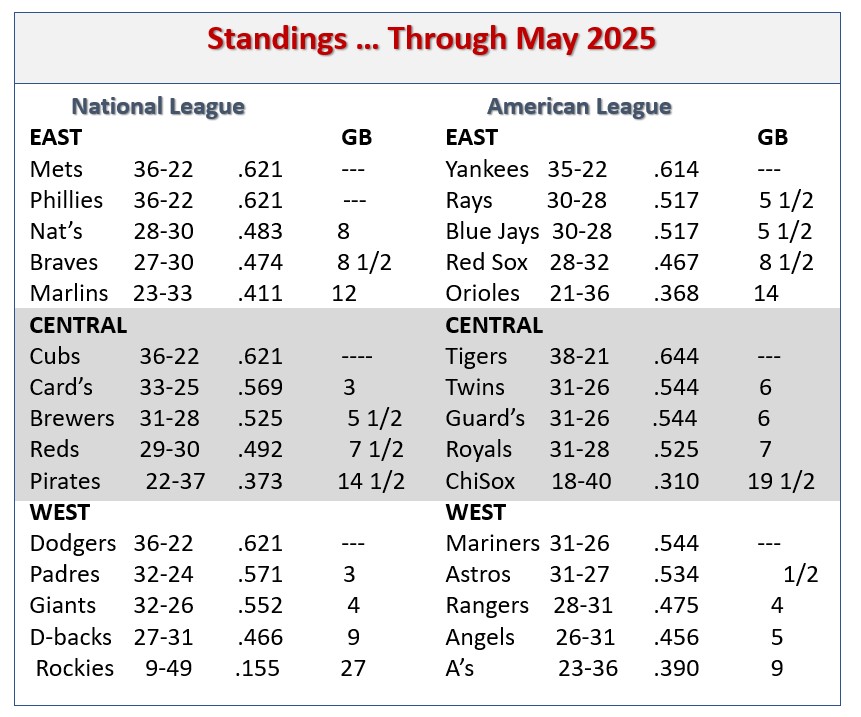

- The Rockies went 4-24 in May (losing all eight series), leaving them 9-49 on the season – the worst start to a season in MLB’s Modern ERA. In May, the Rockies were outscored 192 to 85.

- The AL Central was the only division with four teams over .500 in May. (The AL Central is also the only division to have four teams over .500 through May.)

- Los Angeles was home to the home run kings. The Dodgers led the NL with 44 long balls, the Angels led the AL with 42.

——-Team Statistical Leaders for May 2025 ———-

RUNS SCORED

National League –Dodgers (173); Cubs (150); Phillies (141)

American League – Tigers (150); Rays (137); Blue Jays (136)

The fewest runs in May were scored by the Pirates (84). In the American League, it was the Rangers at 93.

AVERAGE

National League – Dodgers (.283); Diamondbacks (.269); Phillies (.265)

American League – Astros (.2785); Blue Jays (.268); Royals (.265)

The lowest team average for May belonged to the Rangers at .210.

HOME RUNS

National League – Dodgers (44); Diamondbacks (39); Cubs (37)

American League – Angels (42); Yankees (41); Blue Jays 38

The Pirates had the fewest home runs in May at 18.

TOTAL BASES

National League –Dodgers (458); Diamondbacks (442); Phillies (419)

American League – Blue Jays (417); Astros (410); Yankees (410)

The Dodgers led MLB in May Slugging Percentage at .482. The Yankees led the AL (.459)

DOUBLES

National League – Nationals (56); Diamondbacks (53); Reds (52)

American League – Yankees (50); White Sox (50); Athletics (49); Tigers (49)

TRIPLES

National League – Rockies (9); Diamondbacks (6); five with five

American League – Royals (8); Yankees (6); Red Sox (4); Guardians (4)

STOLEN BASES

National League – Brewers (40); Cubs (30); Nationals (26)

American League – Rays (49); Rangers (27); Orioles (25)

The Tigers stole the fewest sacks in May at seven – in ten attempts. The Giants stole the fewest May bags in the NL – nine in fifteen attempts.

WALKS DRAWN

National League – Dodgers (107); Mets (102); three with 95

American League – Yankees (109) Blue Jays (108); A’s (96)

The Dodgers led MLB in May on-base percentage at .357. The Blue Jays led the AL at .345. The Rangers had MLB’s lowest May OBP at (.279). The Rockies anchored the NL at .280.

BATTER’S STRIKEOUTS

National League – Reds (262); Rockies (257); Pirates (240)

American League – Angels (283); Red Sox (257); Tigers (247)

Padres’ batters fanned the fewest times in May (184). The Royals fanned the fewest times in the AL at 189.

__________________________________________________

EARNED RUN AVERAGE

National League – Giants (2.64): Mets (3.08); Braves (3.08)

American League – Rangers (2.98); Twins (3.11); Royals (3.12)

The Athletics had the highest May ERA at 6.88. Also over 5.00 were the Rockies (5.91); Diamondbacks (5.33) and Orioles (5.21). All these teams were under .500, with a combined 31-80 record.

STRIKEOUTS

National League – Phillies (269); Braves (250); Dodgers (238)

American League –Astros (276); Tigers (257); Yankees (254)

The Astros averaged an MLB-best 10.24 strikeouts per nine innings in May. The Phillies averaged an NL-best 9.53. Six teams averaged nine whiffs per nine or better. By comparison, the Mets led MLB in K/9 in 1990 at 7.61; The Indians led in 1970 at 6.67; and the Dodgers led in 1950 at 5.00.

FEWEST WALKS SURRENDERED

National League – Cubs (63); Cardinals (69); Giants (71)

American League – Royals (60); Twins (60); Mariners (72)

The Royals walked an MLB-lowest 2.15 batters per nine innings in May. The Angels walked an MLB-worst 4.30 batters per nine frames.

SAVES

National League – Phillies (12); Cardinals (11); four with eight

American League – Twins (10); Blue Jays (10); three with eight

The A’s blew the most saves in May– nine 13 opportunities.

Walks+Hits/Innings Pitched (WHIP)

National League – Giants (1.12); Cubs (1.15); Braves (1.18)

American League: Twins (1.13); Blue Jays (1.15); Royals 1.16; Tigers (1.16)

Bonus Stats:

- The A’s gave up an MLB-high 56 home runs in May. The Giants gave up an MLB-low 17 home runs.

- Rangers’ pitchers held opponents to an MLB-low .218 average in May. The Rockies’ staff was touched for an MLB-high .300 average.

- The Twins’ strikeouts-to-walks ratio for May topped MLB at 3.95. The Rockies had MLB’s worst ratio at 1.81.

—-MAY HIGHLIGHTS—-

Wait for the Big Finish

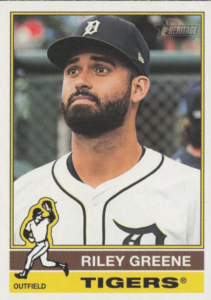

On May 2, the Tigers came up in the top of the ninth innings in a 1-1 tie with the Angels, but ended the pitchers’ duel with an eight-run top of the final frame. Tigers’ DH Riley Greene scored and drove in the first run of the frame with a solo home run off Kenley Jansen. Nine batters later, Greene scored the final run and drove in the final three runs of the contest with a three-run homer off Jake Eder. It was the first time in AL/NL history a player had hit two ninth-inning homers in a game.

On May 2, the Tigers came up in the top of the ninth innings in a 1-1 tie with the Angels, but ended the pitchers’ duel with an eight-run top of the final frame. Tigers’ DH Riley Greene scored and drove in the first run of the frame with a solo home run off Kenley Jansen. Nine batters later, Greene scored the final run and drove in the final three runs of the contest with a three-run homer off Jake Eder. It was the first time in AL/NL history a player had hit two ninth-inning homers in a game.

Who Did What?

Astros’ CF Jake Meyers came into the game on May 3 (versus the White Sox) batting ninth and hitting .262, with no home runs and six RBI in 30 games. Those numbers changed in a hurry. As the Astros prevailed 8-3, Meyers went four-for-four, with two homers, a triple and a double, collecting (a franchise record-tying) 13 total bases, scoring twice and driving in seven tallies.

Baltimore Flyover (The wall, that is.)

On May 4, as the Royals beat the Orioles 11-6 in an afternoon title at Camden Yards – the ball was flying. The two teams hit a total of 11 roundtrippers in the game. The Royals launched a franchise-high seven and the Birds went yard four times. Further, ten of the 11 long balls were solo homers which, according to the Elias Sports Bureau, tied an MLB record. Overall, nine players went yard. The Royals got two homers from 3B Maikel Garcia and one each from LF Jonathan India; SS Bobby Witt, Jr.; 1B Vinnie PasquaNtino; 2B Michael Massey; and C Luke Maile. The Royals got two homers from 2B Jackson Holliday and one each from CF Cedric Mullins and RF Ryan O’Hearn. Massey’s ninth-inning two-run home run as the only one that wasn’t a solo shot.

Royals’ starter Michael Lorenzen gave up all four Orioles’ homers (over a 4 2/3-inning outing). The Orioles, on the other hand, had five different pitchers surrender long balls.

You Chose Well, Grasshopper

On May 4, the Texas Rangers dismissed Offensive Coordinator Donnie Ecker and on May 6 brought on Brett Boone as hitting coach. Well, on Boone’s first day on the job, the Rangers banged out sixteen hits in a 6-1 win over the Red Sox in Fenway (evening the Rangers’ 2025 record at 18-18). Six Rangers had multi-hit games and only the number-nine hitter in the starting lineup went hitless. An omen? Hard to say. After all the Rangers did collect 12 hits in the game before Boone came on the scene (an 8-1 win over the Mariners in Texas). But certainly, a good first day on the job for Boone.

Side note: Through May 4, the Rangers had scored three or fewer runs in 22 of its 35 games (63%). From May 6-31, they scored three or fewer runs in 14 of 23 games (58%).

Extra? Extra? Read All About it.

On May 6, the Cubs and Giants were locked in a tight one – tied at five apiece after ten innings. Then things loosened up a bit, as the Giants tallied nine in the top of the eleventh and eventually won 14-5 – the fifth largest extra-inning margin of victory in the Modern Era (post-1900). It went like this:

Cubs’ Ryan Pressley pitching

- Giants’ pinch runner Christian Koss started the inning on second base (replacing LaMonte Wade, Jr.);

- LF Heliot Ramos doubled, Koss going to third;

- C Patrick Bailey singled to drive home Koss, with Ramos going to third;

- 2B Brett Wisely bunted, Ramos scored, Bailey went to second, and Wisely reached first;

- RF Mike Yastrzemski walked, loading the bases;

- SS Willy Adames was hit by a pitch, forcing in a run;

- CF Jung Hoo Lee hit an RBI single to right, bases remained loaded;

- 3B Matt Chapman singled to left, driving in two runs – runners now on first and second;

- DH Wilmer Flores hit an RBI single to left, runners now on first and third;

Caleb Thielbar replaces Pressley on the mound.

- Koss struck out;

- Ramos hit an RBI double to left, runners now on first and third;

- Bailey hit an RBI sacrifice fly to center;

- David Villar pinch hit for Wisley and struck out to end the carnage.

The inning: Nine runs on six hits, a walk and a hit-by-pitch.

For the who like to know such things, the most runs scored in any extra-inning was 12 – by the Rangers in a July 3, 1983, 14-inning, 16-4 win over the Athletics. Notably, like the Giants (above), they accomplished the feat without the benefit of a home run … eight hits (three doubles), four walks, a wild pitch and an Athletics’ error.

200 for Bregman

On May 7, as the Red Sox topped the Rangers 6-4 in Boston, BoSox’ 3B Alex Bregman went three-for-four, with two runs scored and three RBI. One of his hits was a fourth-inning solo home run off Tyler Mahle – the 200th roundtripper of Bregman’s 10-season MLB career. Bregman finished May at .299-11-35 on the season.

The Bronx Bomber Tradition

On May 9, 22-year-old (rookie-qualified) Yankee left fielder Jasson Dominguez went deep three times in a Yankees 10-2 win over the Athletics in Sacramento. It was his first MLB multi-homer game and included a first-inning solo homer (hit left-handed off Osvaldo Bido). He also drove in a run with a sac fly off Bido in the fifth; hit a solo homer, batting right-handed, off Hogan Harris in the seventh; and capped off his day with a Grand Slam (back to the port side) off Elvis Alvarado in the eighth. Dominguez hit only one other home run in May – a walk-off game winner off Luke Jackson of the Rangers in a 4-3 Yankees win on May 21.

On May 9, 22-year-old (rookie-qualified) Yankee left fielder Jasson Dominguez went deep three times in a Yankees 10-2 win over the Athletics in Sacramento. It was his first MLB multi-homer game and included a first-inning solo homer (hit left-handed off Osvaldo Bido). He also drove in a run with a sac fly off Bido in the fifth; hit a solo homer, batting right-handed, off Hogan Harris in the seventh; and capped off his day with a Grand Slam (back to the port side) off Elvis Alvarado in the eighth. Dominguez hit only one other home run in May – a walk-off game winner off Luke Jackson of the Rangers in a 4-3 Yankees win on May 21.

Dominguez is now the youngest Yankee with a three-homer game (22 years-91 days), edging out Joe DiMaggio (22 years-200 days). #InBaseballWeCountEverything. It was also reported that Dominguez became the first player to hit three home runs in a game, hit homers both right- and left-handed in a game, hit a Grand slam and hit a walk-off homer all in the same month.

Fedde Shutout – A Rare Bird

On May 10, Erick Fedde of the Cardinals tossed his first MLB shutout and first MLB complete game in eight MLB seasons. It came in his 137th start. Fedde gave up six hits and no walks (with eight strikeouts) in a 10-0 win over the Nationals in Washington. It was just the third single-pitcher shutout of the season. It was also the Cardinals’ first single-pitcher shutout since August 22, 2022. Fedde threw 109 pitches (68 strikes) in his outing.

Now that’s Embarrassing

The Rockies had a tough May, going 4-24, leaving them 9-49 on the season. The most embarrassing moment may have come on May 10, when the Rox lost to the Padres 21-0 in Colorado. Rockies’ batters tallied just five hits, while Rockies’ pitchers gave up 24 hits, including five home runs (RF Fernando Tatis, Jr.; SS Xander Bogaerts; 2B Jake Cronenworth; 1B Gavin Sheets; LF Jason Heyward. The Padres missed the Modern Era (post-1900) record for runs scored when shutting out an opponent by just one run. There have been two 22-0 whitewashings. On September 16, 1975, the Pirates beat the Cubs (at Wrigley) by that score. On August 31, 2004, the Indians trounced the Yankees 22-0 in New York. Pre-1900, the Providence Grays beat the Philadelphia Quakers (now Phillies) 28-0 on August 21, 1883.

Oh, and by the way, Padres’ pitcher Stephen Kolek threw a nine-inning shutout (don’t see those too often any more), giving up five hits, walking two and fanning seven. It was Kolek’s first career complete game and first shutout (in just his fourth MLB start). Kolek made his MLB debut in 2024, getting in 42 games for San Diego (all in relief) and going 3-0, 5.21. Through May of this season he was 3-1, 4.11 in five starts.

Let’s Change Things Up a Little

The Reds came into their May 10 game at Houston with a 20-21 record, having won only one of their last seven games and having scored a total of ten runs in their last six games. Then BOOM, the Reds matched their offensive output of the previous six games by plating ten runs versus Houston in the top of the very first inning. The Reds sent 14 batters to the plate that inning and scored tens runs on five hits (three singles, a double and a home run), while also benefiting from five walks and a hit batsman. They ultimately won the game 13-9. They then went on to lose their next three games, tallying a total of three runs. But in a see-saw month, after those three losses, they went on a five-game winning streak, outscoring their opponents 26-8.

1,000 for Freddy

On May 12, as the Brewers lost to the Guardians 5-0 in Cleveland, Brewer starter Freddy Peralta lasted 5 1/3 innings, giving up four runs and taking the loss. He did, however, fan four batters and the third of those strikeouts – 2B Daniel Schneemann to end the fifth inning was Peralta’s 1,000th career strikeout- making him the fastest pitcher to reach 1,000 Ks as a Brewer (187 games/804 2/3 innings). Peralta is in his eighth season (all as a Brewer).

They Call Him The Streak

On May 14, as the Phillies won the first game of a doubleheader against the Cardinals by a 2-1 score, Phillies’ DH Kyle Schwarber took a zero-for-four collar. Hardly seems worth a highlight, unless you consider that it was the first time in 48 games that Schwarber failed to get on base. It was the fourth-longest such streak in Phillies Modern-Era (post-1900) history. The Phillies’ record belongs to Mike Schmidt at 56 games. The all-time record is 84 games by Ted Williams). Schwarber’s 46-game on-base streak went back to September 23, 2024. During the streak, he went .262-16-37, with 33 walks.

One For the Money … Two for the Sho(hei)

Timing isn’t everything, but it is something. On May 15, 51,272 fans packed Dodger Stadium for Shohei Ohtani Bobblehead Night … a bobblehead commemorating his “unicorn” 2024 fifty+ homer/50+ steal season). As usual, Ohtani did not disappoint, going two-for-six, with two home runs and six RBI in a 19-2 win over the Athletics. Side Note: On April 2, the Dodgers handed out Ohtani bobbleheads commemorating his third unanimous NL MVP Award (2021-23-24). In that game, Ohtani went three-for-five and won the game with a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth (Dodgers 5 – Braves 5). Nice timing.

A Nice Round Number

On May 16, as the Phillies topped the Pirates 8-4 in Philadelphia, Phillies’ 1B Bryce Harper went three-for-four (all singles) with two runs scored and two RBI. His first RBI of the game, coming in the fifth inning, was Harper’s 1,000th career run driven in (coming in his 14th season/1,697th career game. More #InBaseballWeCountEverything – In an MLB.com report, Todd Zolecki noted that made Harper just the 14th MLB player to rack up 1,000 runs scored, 1,000 walks and 1,000 RBI before his 33rd birthday.

Immaculately Done, Mr. Quantrill

On May 18, as the Marlins topped the Rays 5-1 in Miami, Marlins’ starter Cal Quantrill tossed five innings of one-run ball for the win (two hits, one run, two walks, six strikeouts). He carved out a little spot in MLB history in the top of the fourth – tossing 2025’s first Immaculate Inning (nine pitches, three outs, three strikeouts). The victims were the 5-6-7 hitters: 1B Jonathan Aranda, LF Christopher Morel and CF Kameron Misner. For those who like to know such things, there have been more than 100 Immaculate Innings. Dipping a toe into the research, I found that Baseball-Almanac.com reports 115 such occurrences; The Sporting News 116 and an article on MLB.com 118. One thing that is agreed upon is that Immaculate frames are becoming more common, with more nine-pitch, three-strikeout innings reported between 2000 and 2025 than from 1889 through 1999,

Not as Complete a Day as Hoped For

On May 18, in his 33rd MLB start, Pirates “phenom” Paul Skenes pitched his first MLB complete game – giving up just three hits and one rum (walking one and fanning nine) in eight innings. Unfortunately, all he got for that sharp outing was a loss, as four Phillies’ pitchers held the Pirates scoreless. The loss put Skenes at 3-5, 2.44 (after ten starts) on the season.

Rolling a 300

On May 19, as the Phillies topped the Rockies 9-3 (in Colorado), Kyle Schwarber led off the top of the ninth inning with a 466-foor home run to right field (off Scott Alexander). It was his 16th of the season and, perhaps more important statistically, his 300th career dinger. Schwarber finished May with a .232-19-43 stat line on the season. Sidenote: Schwarber seems to have found a “home” in Philly. In seven seasons before coming to Philadelphia (2015-2021 … Cubs, Nationals, Red Sox), Schwarber hit a total of 153 long balls in 664 games. In three seasons and change with the Phillies 2022-2025) he has hit 150 home runs in 523 games.

Breaking Out in the Eighth

On May 23, in a 19-5 win over the Orioles in Boston, the Red Sox dropped a “Baker’s Dozen” runs on the Birds in the eighth inning. (For you youngsters a “Baker’s Dozen” is 13.) The Red Sox sent 18 batters to the plate in the frame – collecting 12 hits (five singles, five doubles, two home runs) and two walks. Every player in the lineup scored at least once (four scored twice). DH Rafael Devers had a single and a Grand Slam (two runs, five RBI in the inning), while RF Rob Refsnyder had a three-run homer and a single (four RBI, two runs scored). Orioles’ pitchers Cionel Perez and Emmanuel Rivera (a corner infielder by trade) threw a combined 67 pitches in the inning. For those who like know such things, the most runs ever scored by a team in the eighth inning of an MLB game is 16 – by the Rangers (also against the Orioles) in a 26-7 win on April 19, 1996. In that inning, the Rangers recorded eight hits, but benefited from eight walks and a wild pitch. The Orioles’ pitcher in that frame were Armando Benitez, Jesse Orosco and (infielder) Manny Alexander.

Out-Madduxing the Professor

On May 25, Tigers’ lefty Tarik Skubal threw a rare “Maddux” – a nine-inning shutout using less than 100 pitches (named such in honor of Hall of Famer Greg Maddux). In running his season record to 5-2, 2.49, Skubal shutout the Guardians in a 5-0 Tiger win. Skubal fanned 13 batters in his 94-pitch outing (the most strikeouts ever in a “Maddux.”) Maddux himself never fanned more than nine batters in a “Maddux.”

Don’t Be in Such a Hurry

On May 25, Braves’ starter Chris Sale pitched six scoreless frames (two hits, three walks, eight strikeouts), as the Braves topped the Phillies 9-3. His final strikeout – 3B Edmundo Sosa to end the sixth inning, was the 2,500th of Sale’s 15-season MLB career. It made him the 40th MLB pitcher to reach that milestone and he got there faster (in innings) than any other pitcher (2,026 innings). The previous pace-holder was Randy Johnson, who reached 2,500 strikeouts in 2,107 2/3 innings (in his 12th MLB season).

How Things have Changed – A Complete Game is a Highlight

On May 31, The Rays’ Zack Littell – making his 59th career start and 214th mound appearance in eight MLB seasons, tossed his first MLB career complete game. He gave up three runs on ten hits and one walk (six strikeouts) in the 117-pitch outing (a 16-3 Rays win over the Astros in Houston).

Not A Great Day for the Home Crowd

On May 31, the Diamondbacks were in a deep hole even before many of the 29,434 fans at Chase Field were in their seats. In the top of the first inning, the Nationals scored nine runs off pair of Diamondbacks’ hurlers before an out was even recorded.

It went like this.

Brandon Pfaadt on the mound.

- CF CJ Abrams hit by a pitch on an 0-2 count;

- LF James Wood singled to right, Abrams going to third;

- 1B Nathaniel Lowe hit an RBI double to left;

- 2B Luis Garcia Jr. hit a two-run double to right;

Hits to all three fields already.

- DH Josh Bell hit by a pitch on a 2-2 count;

- CF Robert Hassell III singled to center, loading the bases;

- C Kiebert Ruiz hit a two-run double to CF;

- 3B Jose Tena hit a two-run double to right;

With seven runs in, a runner on second and just 36 pitches thrown, Pfaadt was replaced on the bump by Scott McGough.

- RF Daylen Lile laced McGough’s second pitch for an RBI double to CF;

- Abrams hit by a pitch for the second time in the inning;

Side Note: Abrams tied the MLB record for most time hit by a pitch in an inning and was hit again in the sixth frame to tie the record for most times hit by a pitch in a game.

- Wood hit a ground ball, RBI single to CF;

- Lowe struck out swinging for the first out (nine runs already in).

The Nationals eventually went on to score one more run in the first inning and then hang on for a 11-7 win. According to the Elias Sports Bureau it was the second most runs ever scored by an MLB team before making its first out of a game. The Red Sox scored ten runs before the first out in the first inning of a 25-8 win over the Marlins (in Boston) on June 27, 2003. The Nationals did tie the NL record for runs scored before making a first out.

200 and Counting

On May 31, as the Dodgers topped the Yankees 18-3, LA third baseman Max Muncy went three-for -six, with three runs scored, seven RBI and two home runs. The first of the two long balls – a three-run shot in the second inning – was Muncy’s 200th career MLB roundtripper.

––INDIVIDUAL STAT LEADERS FOR MAY—

BATTING AVERAGE (at least 75 at bats)

American League: Jose Ramirez, Guardians (.386) Jacob Wilson. Athletics (.368); Ryan O’Hearn, Orioles (.365)

National League: Freddie Freeman, Dodgers (.410); Heliot Ramos, Giants (.347); TJ Friedle, Reds (.344)

The lowest May average among players with at least 75 at bats belonged to the Red Sox’ infielder Kristian Campbell at .134 (11-for-82).

HITS

American League: Jose Ramirez, Guardians (39); Jacob Wilson, A’s (39); three with 37

National League: Freddie Freeman, Dodgers (43); Trea Turner, Phillies (38); James Wood, Nationals (35)

The Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani led all MLBers in May extra-base hits with 21 – five doubles, one triple and 15 home runs.

HOME RUNS

American League: Cal Raleigh, Mariners (12); Aaron Judge, Yankees (11); Taylor Ward, Angels (10)

National League: Shohei Ohtani, Dodgers (15); Kyle Schwarber, Phillies (10); Pete Crow-Armstrong, Cubs (9)

The Yankees’ Aaron Judge all hitters with at least 75 at bats in May slugging percentage at .798. The Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani the NL at .782

RUNS BATTED IN

American League: Rafael Devers, Red Sox (33); Taylor Ward, Angels (28); Cal Raleigh, Mariners (26)

National League: Pete Crow-Armstrong, Cubs (29); Shohei Ohtani, Dodgers (27); Seiya Suzuki, Cubs (27)

RUNS SCORED

American League: Aaron Judge, Yankees (25); Zach Neto, Angels (23); Jose Ramirez, Guardians (22)

National League: Shohei Ohtani, Dodgers (31); CJ Abrams, Nationals (24); Mookie Betts, Dodgers (23); Kyle Schwarber, Phillies (23)

DOUBLES

American League: Lawrence Butler, A’s (10); Ryan Mountcastle, Orioles (9); Miguel Vargas, White Sox (9); Bobby Witt, Jr., Royals (9)

National League: Seiya Suzuki, Cubs (12); Freddie Freeman, Dodgers (10); Nico Hoerner, Cubs (10)

TRIPLES

American League: Jarren Duran, Red Sox (3); Bobby Wit, Jr., Royals (3); four with two

National League: Jordan Beck, Rockies (3); Austin Hayes, Reds (3); nine with two

STOLEN BASES

American League: Chandler Simpson, Rays (16); Jose Caballero, Rays (12); Bobby Witt, Jr., Royals (11)

National League: Jackson Chourio, Brewers (9); Francisco Lindor, Mets (8); Trea Turner, Phillies (8); Kyle Tucker, Cubs (8)

The White Sox’ Luis Robert, Jr. and Jorge Mateo of the Orioles tied for the most May bases stolen without getting caught (9).

BATTER’S STRIKEOUTS

American League: Zach Neto, Angels (39); Tyler Soderstrom, A’s (37); Taylor Ward, Angels (37)

National League: Michael Toglia, Rockies (40); Oneill Cruz, Pirates (38); Tyler Stephenson, Reds (37)

WALKS

American League: Rafael Devers, Red Sox (22); Vlad Guerrero, Jr., Blue Jays (21); Gleyber Torres, Tigers (21)

National League: Marcell Ozuna, Braves (22); Juan Soto, Mets (20); Kyle Schwarber, Phillies (19)

The Highest on-base percentage among players with at least 75 May at bats was .468, by the Red Sox’ Rafael Devers. The NL leader was the Dodgers’ Freddie Freeman at .462.

PITCHING VICTORIES

American League: Zack Littell, Rays (4-0); Framber Valdez, Astros (4-1); Jhoan Duran, Twins (4-1)

National League: Ranger Suarez, Phillies (4-0); Robbie Ray, Giants (4-1); Zack Wheeler, Phillies (4-1)

The Rockies’ Antonio Senzatela led MLB in May losses (0-6, 9.10) in six starts.

EARNED RUN AVERAGE (minimum 20 May innings)

American League: Kris Bubic, Royals (0.56); Nathan Eovaldi, Rangers (0.68); Carlos Rodon, Yankees (1.47)

National League: Andrew Abbott, Reds (0.55); Bailey Falter, Pirates (0.76); Chris Sale, Braves (1.11)

The highest ERA among pitchers with at least 25 May innings or four May starts was 9.10 by the Rockies’ Antonio Senzatela (0-6, 9.10 in six starts, 28 2/3 innings).

STRIKEOUTS

American League: Tarik Skubal, Tigers (59 K / 41 IP); Will Warren, Yankees (43K / 28 IP); Framber Valdez, Astros (42 K / 42 IP)

National League: Robbie Ray, Giants A (45 K / 39 IP); Sonny Gray, Cardinals (43 K / 34 IP); Dylan Cease, Padres (42 K / 34 IP); MacKenzie Gore, Nationals (42 K / 27 1/3 IP)

WALKS + HITS/INNINGS PITCHED (at least 25 May innings)

American League: Tarik Skubal, Tigers (0.59); Joe Ryan, Twins (0.72); Kevin Gausman Blue Jays (0.84)

National League: Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Dodgers (0.80); Zack Wheeler, Phillies (0.81); Bailey Falter, Pirates (0.84)

Among pitches with at least 25 Mays innings, the Dodgers’ Yoshinobu Yamamoto held batters to the lowest average at .146.

SAVES

American League: Jhoan Duran, Twins (7); Emmanuel Clase, Guardians (70; Carlos Estevez, Royals (7); Jeff Hoffman Blue Jays (7)

National League: Ryan Helsley, Cardinals (9); Trevor Megill, Brewers (7); Kyle Finnegan, Nationals (7)

Ryan Helsley of the Cardinals saved the most games without a blown save in May (nine).

Bonus:

Among pitchers who faced at least 75 batters in May:

- The Nationals MacKenzie Gore fanned the most batters per nine innings at 13.83;

- The Blue Jays’ Kevin Gausman had the best strikeouts-to-walks ratio at 33.0. (He walked one batter and fanned 33 in 32 innings.)

Primary Resources: Stathead.com; Baseball-Almanac.com; MLB.com

Baseball Roundtable – Blogging Baseball Since 2012.

Baseball Roundtable is on the Feedspot list of the Top 100 Baseball Blogs. For the full list click here.

I tweet (on X) baseball @DavidBaseballRT

Follow Baseball Roundtable’s Facebook Page here. More baseball commentary; blog post notifications; PRIZES.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research (SABR); Negro Leagues Baseball Museum; The Baseball Reliquary.

P 1118