With the annual TwinsFest in full swing and Spring Training just around the corner, BBRT would like to take a look at the rich family heritage that is the foundation of the Minnesota Twins MLB franchise.

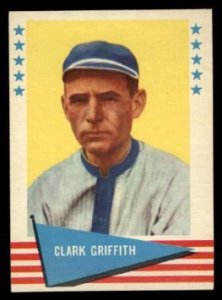

THE FOUNDATION OF THE TWINS – It all goes back to Hall of Famer Clark Griffith (center).

When Calvin Griffith moved the Washington Senators to Minnesota in 1961, he brought with him more than a ball club. He brought a family history with deep roots in our national pastime. Those roots go back to Baseball Hall of Famer Clark Griffith – the only person ever to serve at least twenty years as a player, as a manager and as an owner. Griffith is also the only Hall of Famer ever to have saddled Jesse James’ horse (more on that later).

Baseball is rich in statistics, so before getting into the life and times of Clark Calvin Griffith, here are a few meaningful statistics and facts:

- In twenty major seasons (between 1891 and 1914) as a right-handed pitcher, Griffith went 237-146, with a 3.31 ERA.

- Griffith was a twenty-game winner seven times, with a high of 26 wins (14 losses) for the 1895 Chicago Colts/Orphans (the franchise that eventually became the Cubs). He was a 20-game winner for Chicago in six consecutive seasons (1894-99).

- Griffith led the NL in ERA once, complete games once and shutouts once. He also led the AL in winning percentage once and shutouts once.

- Griffith’s major league playing career included stints with the St. Louis Browns, Boston Reds, Chicago Colts/Orphans, New York Highlanders, Cincinnati Reds, and Washington Senators

- As a manager, Griffith ran up a 1,491-1,367 record over 20 seasons.

- In 1901, Griffith managed the Chicago White Stockings to the first-ever American League Pennant. Serving as player-manager, he also went 24-7 on the mound.

- In 1903, Baltimore’s AL franchise moved to New York – to become the Highlanders and, eventually, the Yankees. Griffith was the Yankee franchise’s first manager in New York.

- Griffith’s managerial career included stints with the Chicago White Stockings (Sox), New York Highlanders (Yankees), Cincinnati Reds and Washington Senators.

- Ban Johnson, Charles Comiskey and Griffith are credited with being the driving forces behind the successful establishment of the American League – with Griffith playing a key role in getting a significant number of National League players to make the “jump” to the new league.

- As an owner, Griffith brought the World Series to Washington D.C. in 1924, 1925 and 1933 (World Series Champions in 1925=4).

So, how did this baseball journey begin – and how did the Senators’ franchise end up in Minnesota? It’s a story of perseverance in the face of difficult times and tough odds, passion for the national pastime and a deep sense of family. It is – for the most part – the Clark Griffith story. And, despite taking place primarily in Missouri, Illinois and Washington D.C., it’s a story that helped shape the future of baseball in Minnesota.

Clark Griffith was born November 20, 1869 on a farm in Clear Creek, Missouri. The family – his father, mother and four siblings – who had moved to Missouri from Illinois were as close to “dirt poor” as you could get. Things only got worse when Clark was two-years-old and his father was mistakenly shot and killed by a deer hunter. Clark’s mother Sarah Anne Griffith was left alone with five children and one on the way. The family struggled to keep the farm going – and worried about the ongoing health of frail young Clark. As he grew older, Clark – suffering what was later diagnosed as malarial fever – developed an interest for baseball, as a spectator and water boy for a local team.

Jesse James and Clark Griffith

After his father’s death, Clark Griffith’s mother would pick up a little extra – and much–needed money – by putting travelers up overnight in their large farm house. One of those traveling groups was made up of Jesse and Frank James and two of the Younger brothers. On the morning of their departure, Jesse asked young Clark to saddle up the horses and bring them from the barn to the house. It was meeting Clark never forgot, and a story he liked to tell.

As Griffith reached his teen years, his mother – looking for a better life – moved the family to Normal, Illinois and opened a boarding house. Clark maintained his passion for baseball, but being small for his age, did not play organized ball (not even for his high school team). He did, however, manage to work his way into a variety of pickup games, where the 5-foot six-inch, 156-pound right-hander began building a reputation as a pitcher.

In 1887, the now 18-year-old Griffith made it into organized ball, pitching for the Bloomington (IL) Reds of the Central Inter-State League. It was there that he got his first big break. During Bloomington’s 1988 season, Griffith was called upon to pitch an exhibition game against the Milwaukee Brewers team from the much more prestigious Western Association. Griffith performed well and came away with a $225 per month Milwaukee contract. What followed were stops in: Milwaukee of the Western Association (1988-89); St. Louis and Boston of the American Association (1891); Tacoma of the Pacific Northwestern League (1892); and Oakland of the California League (1893). Griffith’s season with the Oakland Colonels – when he won 30 games (17 losses), with a, 2.30 ERA and 47 complete games in 48 starts – earned him a late season move to the National League Chicago Colts (Cubs) and, in 1894, he began his National League streak of six consecutive 20-plus win seasons.

Not an overpowering pitcher, Griffith earned the nickname “The Old Fox” for his ability to get hitters out with a combination of sharp breaking pitches, changes of speed and even psychological warfare.

The Old Fox Outfoxes the Competition

“Griff wasn’t very big or very strong and he didn’t have enough of a fastball to knock your hat off, but he knew how to pitch – and he had the nerve of a burglar … The hitters in the national league called him The Old Fox, because they couldn’t figure out how such a slow-balling pitcher could beat them without resorting to tricks. While the batters fumed, Griff, at all times the picture of poise and confidence, struck them out by stalling until they were nervous wrecks, quick-pitching them when they weren’t ready, by scraping the ball against his spikes and taking advantage of the odd twists that could be achieved with a lacerated cover, and by needling the batters with as glib and caustic a tongue as the game has ever known.

Ed Fitzgerald, May 1954 Sport (magazine) … “Clark Griffith – the Old Fox”

While building a Hall of Fame career as a player, Griffith had also developed a keen interest in – and did all he could to learn about – the business side of the game. He saw baseball as his long-term future – wanting to be a manager, and someday even a team owner. Things took a step in that direction as the new century came around and Ban Johnson and Charley Comiskey consulted with Griffith on plans for the establishment of a second major league – with Griffith assuring Johnson and Comiskey that, if team owners and finances could be recruited, he could bring a significant number of current National League players into the fold. In a move involving demands from the Ballplayers Protective Association (of which Griffith was vice-president) and the National League’s apparent unwillingness to negotiate (the players wanted, among other things, to increase the salary limit from $2,400 a season to $3.000), Griffith paved the way for players to move to the new American League. Later, as he looked back on his baseball career, Griffith always listed getting the American League off the ground as one of his proudest accomplishments. And, eventually, the Twins would play in the American League.

At least partially in recognition of Griffith’s role in that making the American League a reality, Comiskey gave Griffith his chance to manage – as player-manager of the Comiskey-owned Chicago White Stockings. And, as noted earlier, Griffith delivered 24 wins from the pitching rubber and the AL’s first pennant from the manager’s seat. Griffith went on to manage the White Sox, New York Highlanders and Cincinnati Reds between 1901-1911.

In 1912, the managerial post with the Washington Senators opened and Griffith, who had managed the Cincinnati Reds for the previous three seasons, saw a two-edged opportunity – to get back to the American League and to pursue the ownership position he had long desired. He took the job – on the condition that he be allowed to purchase 10 percent ownership in the franchise. He financed the purchase with $7,500 in savings and $20,000 loan secured by his ranch (bought with his earnings as a player) in Helena, Montana.

Griffith would maintain an ownership position in the franchise (that, in 1961 became the Twins) until his death in 1955 – but I’m getting ahead of myself. To condense the ownership part of the Clark Griffith story, he was both an owner and manager through the 1920 season. However, in 1919, he partnered with grain broker William M. Richardson to acquire approximately 80 percent ownership of the team and, after the 1920 season, he devoted himself solely to his executive/ownership duties. As an owner. Griffith became known for his dedication to the game, recognition of baseball talent, business sense and frugality, commitment to family and (this possibility related to frugality) pioneering role in signing Cuban ballplayers. Remember these traits; we’ll see them again (in Minnesota).

Coincidentally, just as Clark Calvin Griffith was pursuing an ownership position in the American League’s Washington club, his sister-in-law (Jane Robertson) gave birth to the second of her seven children – Calvin Robertson, born December 1, 1911 in Montreal, Quebec. Times were hard for the Robertson’s. Money was tight and Calvin’s father James Robertson had issues with alcohol. As more children arrived – there were a total of seven youngsters in the family by 1921 – life became more difficult. It reached a point where Clark Griffith and his wife Addie (who were childless) agreed to take in two of the youngsters – 11-year-old Calvin and his nine-year-old sister Thelma. Although not officially adopted, the pair did legally change their names to Griffith. In 1923, Calvin’s father died (at age 42) and the rest of the family was taken under Clark Griffith’s wing in Washington D.C. Being the first to join the Griffiths in the nation’s Capital would prove a stroke of luck for Calvin and Thelma – and perhaps Minnesota (more on that later).

Calvin Griffith shared (perhaps was influenced by) his uncle Clark Griffith’s love of the game and and served as bat boy for the Washington team from 1922 to 1925. Calvin later attended Staunton Military Academy and George Washington University, where he studied and played baseball (pitcher and catcher).

In 1935, he took his first official position in the Senators’ organization – working as secretary-treasurer for the Chattanooga Lookouts, a Washington farm club. He eventually headed the operations at Chattanooga and then at Charlotte (Hornets) before joining his uncle Clark in the Washington front office in 1941. Over the years, under Clark’s tutelage, Calvin took on more and more responsibility for the team’s operations.

When Clark Griffith passed away in 1955 Calvin and his Sister Thelma Griffith inherited 52 percent ownership of the club and Calvin was elected its president. At that time, the family nature of the baseball business was clearly established – not only were Calvin and Thelma and integral part of the team’s front office (with Thelma playing a key role in the teams finances), their brothers Sherry, Billy and Jimmy also were part of the leadership team.

And the family’s baseball ties went even deeper. Before joining the franchise’s front office (and eventually heading up the farm system), Sherry Robertson played ten seasons in the major leagues (between 1940 and 1952) as a utility player (OF, 2B, 3B. SS) – primarily with Clark Griffith’s Washington club. His best year was 1949, when he hit .251 with 11 home runs and 42 RBI in 110 games. In addition, Thelma’s husband Joe Haynes (a veteran of 14 major league seasons as a player) was appointed a roving minor league pitching instructor. Sister Mildred Robertson served for a time as Clark Griffith’s personal secretary and married future Baseball Hall of Famer Joe Cronin. Cronin was clearly a good fit for the Griffith/Robertson baseball family. Consider his ultimate MLB resume: seven-time All Star in a 20-year playing career with the Pirates, Senators and Red Sox; managed the Senators (1933-34) and Red Sox (1935-45); served as treasurer, general manager and president of the Red Sox; and was president of American League from 1959 to 1973.)

Once he took control of the team, Calvin contused his late uncle’s commitment to baseball, business and family – and when the league approved the Senators move to Minnesota for the 1961 season, Calvin brought his team, his executive (family) team and all that he had learned from is uncle Clark Griffith to the Land of 10,000 Lakes. Given the family’s established dedication to the business of baseball, the move to Minnesota made perfect sense. The Washington club had finished below the league average for seventeen consecutive seasons (topping one million in attendance only once) prior to the move. The Twins finished above the league attendance average and topped one million fans in each of their first Minnesota seasons.

So, following in Clark Griffith’s footsteps – and maybe stretching the stride even a bit longer – Calvin Griffith brought major league baseball to Minnesota in 1961.

In his time at the helm in Minnesota – until he sold the team to Carl Pohlad in 1984 – Calvin was known for his dedication to the game, recognition of baseball talent, business sense and frugality, commitment to family and success in discovering and signing Cuban ballplayers. Sound familiar – the influence of Uncle Clark was clearly long-lasting. What has all this meant for Minnesota fans? Over the years, we have seen:

- big league baseball in three stadiums (Metropolitan Stadium, The HHH Metrodome, Target Field);

- three World Series – with one World Championship;

- ten division titles;

- six American League championships;

- three All Star games;

- Five Hall of Famers in Twins’ uniforms – Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Kirby Puckett, Bert Blyleven, Dave Winfield, Paul Molitor, and even Steve Carlton;

- five MVP seasons – Zoilo Versalles, Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Justin Morneau, Joe Mauer;

- three Cy Young Award winners – Johan Santana (twice), Frank Viola, Jim Perry;

- 14 batting titles – Rod Carew (7), Tony Oliva (3), Joe Mauer (3), Kirby Puckett;

- five home run titles – all by Harmon Killebrew;

- 16 20-game winning seasons – Camilo Pascual (twice), Jim Perry (twice), Jim Kaat, Mudcat Grant, Dean Chance, Bert Blyleven, Dave Boswell, Dave Goltz, Jerry Koosman, Frank Viola, Scott Erickson, Brad Radke, Johan Santana;

- Homer Hankies, bobble heads, Bat Day, Hat Day, Stocking Cap Day (even Fishing Lure Day), Dollar Dog Day (I do love a bargain), Nickel Beer Night (won’t see that again), walleye fingers (this is Minnesota, after all), Harmon Killebrew Day (1974), the Thunderdome decibel readings;

- and much, much more

In short, it’s been a great – and continuing ride. And, it all started with the Hall of Famer to which this post is dedicated: Clark Griffith -baseball man, businessman, family man.

Note: Throughout this post, the Washington franchise is referred to as the Senators. However, the franchise that became the Twins, was known as both the Nationals and the Senators in its history – sometimes as both at the same time. And, it was reported that Clark Griffith actually preferred the Nationals moniker. Sportecyclopedia.com reports that, in 1956, “After more than 50 years of insisting the team was officially called the Nationals, the team finally changes its name to the more commonly called Senators. We’ll save that controversey for another post.

Calvin Griffith and My Family

I always enjoyed Calvin – and found him to be a fan-friendly owner, with little pretense, lots of passion for the national pastime and a genuine affection for the fans of the upper Midwest.

On July 4, 1976, for example, I celebrated the birthday of my father George Karpinski and my softball team’s shortstop Bill Morlock (yes, they were both Independence Day babies, just about 30 years apart) by tailgating beyond the left centerfield fence at the old Metropolitan Stadium (followed by the game, of course).

Who should show up to join our gathering? Twins owner Calvin Griffith and former player, manager and then broadcaster Frank Quilici. We spent considerable time discussing baseball, the Twins and the importance of hot dogs, over a cold brew or two (at least on my part). The Twins, by the way, won 9-4 on a grand slam by Rod Carew.

Just over a year later, I celebrated my 30th birthday (with my friends and family) in a private box at the old Met. Back then, a private box was an enclosed area above the second deck, with a formica table top and plastic chairs – and you could bring in your own food and beverage if you wanted. Calvin sent an employee – in a bow tie and gold vest – with a special birthday note. And, during the game, the Twins-O-Gram displayed “Happy Birthday Super Fan Dave Karpinski.” – at no charge. (Note: Actually, at first it read “Happy Birthday Super Fan Dave Krapinski” – but that was corrected, after I got my picture.

I tweet baseball @#DavidBBRT