This is a tale of two left-handed pitchers named George who also both proved they could handle the bat pretty well.

On this date (September 17 in 1916) a 23-year-old southpaw pitcher – in just his second MLB season – took the mound for the Saint Louis Browns against future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson (Washington Senators). On the surface, it seemed a mismatch.

Johnson was in his tenth major league season – with a career record of 231-145, and a 1.64 career earned run average. He had already led the AL in strikeouts five times (including the four previous seasons) and in victories the three previous seasons. At that point in the 1916 season, he was 25-17, with a 1.84 earned run average – on his way the leading the AL in wins, complete games, innings pitched and strikeouts.

Johnson’s mound opponent had gone 4-4. 2.83 as a rookie in 1915 (with 15 mound appearances and six complete games in eight starts. He came into the game against Johnson with 0-1 record on the year – his one pitching appearance being a 1-0 complete-game loss.

Further, Johnson had solid motivation to top his opponent. The previous season, in a matchup against the same left-hander, Johnson had been bested 2-1 in a pitching duel that saw both hurlers go the distance. Johnson gave up two runs on six hits, the rookie allowed one run on six safeties.

On that September 2016 afternoon, Johnson again was outpitched – despite giving up just one run (unearned) on four hits, while walking two and fanning eight. His opponent, like Johnson, went the distance – pitching a six-hit, two-walk, six-strikeout, shutout. It would, ironically, be his last pitching victory. (Johnson, however, would go on to 166 more wins.) It would not, however, be his last major league game. In fact, the Browns’ starting pitcher would go on to play 13 more seasons, earning his own spot in the Hall of Fame – with his bat and glove, rather than his pitching arm.

Who was that southpaw who won both his matchups against Walter Johnson – giving up just one run in 18 innings? Future Hall of Famer George Sisler, who – like another hitter who came up as a pitcher (Babe Ruth) – would prove master batsman. Playing primarily at first base (where he earned a reputation as an excellent fielder), Sisler collected 2,812 MLB hits, put up a career .340 average, won two batting titles (hitting .407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922), led the AL in stolen bases four times, triples twice, base hits twice (his 257 hits in 1920 would stand as the MLB record until 2004) and runs scored once. Sisler hit over .300 in 13 of his 15 MLB seasons, topping .350 five times. He stole a total of 375 bases, with a high of 51 in 1922. He also had 100+ RBI in four campaigns, 100 or more runs in four seasons and 200+ hits in six seasons.

Overshadowed by the Babe

In 1920, when George Sisler set a then MLB record with 257 hits (and led the AL with a .407 average), he also set a career high with 19 home runes. He was overshadowed by another former left-handed pitcher named George (George Herman “Babe” Ruth) who hit “only” .376, but shattered the MLB home run record with an unheard of 54 round trippers (breaking his own record of 29).

That season, Sisler finished second to Ruth in home runs (54-19); runs (158-137) and RBI (135-122), but did top the Babe in total bases (399-388).

Like Ruth, Sisler would occasionally take a turn on the mound later in his career (twice in 1918 and once each season in 1920, 1925, 1926 and 1928). His career pitching line in 24 games (12 starts) was 5-6, 2.35, with nine complete games and one shutout.

The Sisler – Rickey Connection

Branch Rickey and George Sisler are both in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but their connections run much deeper.

- Sisler’s college coach (at the University of Michigan) was Branch Rickey.

- Sisler’s first MLB manager (with the 1915 Saint Louis Browns) was Branch Rickey.

- In World War I, Sisler served in a chemical warfare training unit commanded by Branch Rickey.

- From 1942 through 1950, Sisler worked as a scout (he reportedly scouted Jackie Robinson) and player development coach for the Dodgers (under Branch Rickey).

- In 1952, when Branch Rickey joined the Pirates’ organization, he hired Sisler as a roving coach.

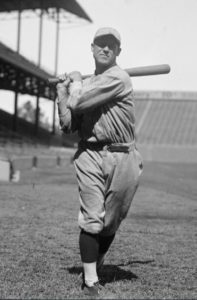

![[George Sisler, University of Michigan (baseball)] (LOC) by The Library of Congress George Sisler photo](https://baseballroundtable.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/3295497074_1b35a93f45_m_George-Sisler.jpg)

Photo by The Library of Congress

Cassius Clay Connection

George Sisler was the son of Mary Whipple and Cassius Clay Sisler.

When he joined the Saint Louis Browns in 1915, Sisler’s manager Branch Rickey – who had witnessed his college pitching and batting prowess (Sisler hit over .400 in his college baseball career) – began working him out at first base and in the outfield. The results, as noted earlier, were spectacular.

Baseball Genes

Two of George Sisler’s three sons made it to the major leagues as players, while the third served as a minor league executive.

- Dick Sisler hit .276 in eight seasons (799 games – Cardinals, Phillies, Reds) as an MLB outfielder/first baseman and went on to manage the Cincinnati Reds (1964-65) and later serve as a coach with the Cardinals, Padres, and Mets.

- Dave Sisler pitched in seven MLB seasons (Red Sox, Tigers, Senators, Reds) going 38-44, 4.33 with 28 saves (247 games, 59 starts).

- George Sisler, Jr. was a general manager for several minor league teams and served as the President of the International League for a decade (1966-76).

Primary resources: Society for American Baseball Research; The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball Forgotten Giant (Rick Huhn, University of Missouri, 2004); Baseball Hall of Fame; Baseball-Reference.com

I tweet baseball @DavidBBRT

Like/Follow the Baseball Roundtable Facebook page here.

Member: Society for American Baseball Research; The Baseball Reliquary; The Negro League’s Baseball Museum.